Hellsdyke

Who builds in Hell?

[Inferno 15: hand-coloured woodcut illustration from La comedia di Dante Aligieri con la commentario di Christophus Landinus (Brescia 1487). Dante—bending, to talk with his old master, Latini—and Virgil, in blue, make their way along the top of the dyke. (Incidentally, the mouseover text here is not mine; it has been carried over from Digital Dante, whence I sourced this image)]

.

Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad (2016) reimagines the historical ‘underground railroad’—the unofficial system of overland routes and safe-houses by which slaves and freedom-seekers would, sometimes, escape the Southern US to free states in the north and Canada—as an actual railway, an underground transport system of large scope, with many secret tunnels, stations and stop-overs. We might wonder who constructed this impressive piece of national infrastructure. It would have cost much money and huge labour to build such a thing overland, and, surely, much more to tunnel out the underground network. ‘Who built it?’ one of Whitehead's fugitives asks, on first reaching a station on the Underground Railroad and peering down the tunnel. ‘Who builds anything in this country?’ the station-master replies. Whitehead is saying: all the actual work in the country is undertaken by the slaves, by Black people, by the oppressed. He’s also saying: a thing like this, the way to freedom is a made thing: freedom doesn’t just spontaneously happen, it must be dug-out, assembled, maintained and repaired. What he is not doing is suggesting any kind of detailed backstory, any implied alt-historical narrative in which 19th-century enslaved people and white abolitionist allies actually constructed this network. This isn’t like The Great Escape, with prisoners taking time out from leaping over a wooden vault to scrape a hundred yards of tunnel out with spoons under the unwitting eyes of camp guards. This is more like the soldier in Wells’s War of the Worlds (1898) who plans, but is never going actually, to excavate vast underground domain for humanity, leaving the Martians the surface. The point of the scene where Wells’s narrator meets this fellow is to characterise him in terms of his over-ambition, his fantasy, his disconnect from reality—he keeps breaking off from the digging to get himself another drink, and to boast to the narrator about how great things will be. We know he’ll never actually create his underworld world. Underground Railroad is, in a way, a War of the Worlds in which the oppressed and enslaved actually did dig-out a huge underground structure. But Whitehead is not really interested in the hows-and-whens, the material plausibilities, of this backstory. His interest is otherwise.

This is to say something about ‘worldbuilding’, in science fiction and in literature more broadly. We can take worldbuilding as the business of rendering a comprehensive, internally consistent and plausibly-accomplished imaginary world in which our story can take place. Plausibility relates to the in-world logic of the work: so Orthanc, a mile high and improbably invulnerable to assault, would violate plausibility in a medieval-set historical novel, but needn’t in the world of The Lord of the Rings, in which various magics obtain. The wall in A Song of Ice and Fire reaches as high as 900 yards: over half a mile high—structural bigness beyond medieval wall-builders, but not implausible in a world, again, containing magic. OK. Some writers spend a lot of time on worldbuilding, and many fans prize both the comprehensiveness and the internal consistency, this latter a particular issue in an age when the main culture texts are not single-author works but team-made, serial productions, released over many years, even decades, into cinemas or on film. What price internal consistency the worldbuilding of, say, Doctor Who, whose later episodes promiscuously and radically contradict many of the worldbuilding tenets of the earlier episodes?—see also: Star Trek, Star Wars.

But worldbuilding also means: generating the as-it-were physical lineaments of a metaphorical articulation. The ‘matrix’ of The Matrix is not compatible with the ‘matrix’ of Matrix: Resurrections, but that matters less than it might, since the matrix is primarily a metaphor (for ideology, for oppression—racism, class, transphobia—and so on). In practical terms, which is to say in terms of the plausibility of the matrix as such, the matrix doesn’t make sense; but the point of these films is not to elaborate a practical, working-model, we-could-build-it virtual reality. I revert, not for the first time, to Samuel Delany’s pithy definition: ‘science-fiction is a radically metaphorical literature, because it aims to represent the world without reproducing it’. So, in Whitehead’s novel, which is a kind of science-fiction (a kind of alt-historical or, in its way, steampunk text): the underground railway, literalised in the novel, is a metaphor for resistance to and escape from slavery, from racism and from oppression. It is a detailed metaphor. The railway is no gleaming high-tech bullet-train to freedom, it is shonky, hand-made, slow, fugitives might have to wait weeks for a train. But it is a way.

Which brings me to Dante. The many internal inconsistencies in the myriad elements that make up the megatext of Star Trek are worried-over, debated, and worked into sometimes torturous, sometimes ingenious and compelling explanations over on the fansite Daystrom Institute. It’s an amazing resource, really: a testament to the imagination and passion of the contributors. One universal solvent for inconsistency is ‘alternate realities’, ‘parallel worlds’—DC’s ‘Crisis on Infinite Earths’ is one famous example of a megatext, having accreted over many years and grown crusty and barnacled with internal inconsistency, waving the alt-reality wand and crashing through a reset to establish the franchise on a more ‘worldbuilt’—a more consistent—basis.

I mean no disparagement if I say that one of the great achievements of the Catholic Church is to create an enormous discursive structure and super-structure that brings together the many various and disparate elements of Christian textuality, tradition, midrash and praxis into one self-consistent and, in the best sense of the word, ‘worldbuilt’ whole. If you are a Catholic, you of course consider the coherence and internal consistency of this ‘world’ to index the fact that it is true; but even if you are not, you must admire the interpretive and imaginative effort that has been put into the megatext, over many centuries, to bring it into its baroquely sublime harmony.

This relates to Dante, a Catholic author whose Commedia seeks to do something similar: not just unifying the theology and ethics of his faith, but also drawing together into a consilience all the bits and pieces of the imagined world of the poem. The world, with Jerusalem as its apex, the vasty hollow terraced spaces of hell beneath this stretching down to the centre of the globe, then on the far side the gigantic mountain of Purgatory in what we now call Australia/New Zealand.

If we ask Milton ‘who built hell?’ he tells us. Which is to say: in the sense that the uninviting vacancy so hugely distant from heaven has been prepared by God for the as-yet-unfallen angels, soon to be devils, we could say ‘God built it’. But the first thing the fallen angels do when they arrive in Hell is to construct a massive, orgulous city: Pandæmonium.

[John Martin’s 1841 painting of Milton’s epic, the titularly misspelled ‘Pandemonium’]

So in terms of the infrastructure within Hell we can say, the devils built it.

What about Dante’s hell? It is a location arranged on multiple terraces, a funnel-shaped space leading down to a great mass of ice in the earth’s centre in which are embedded Satan himself, endlessly devouring the heads of Judas Iscariot, Brutus and Cassius. It possesses a massy stone gateway at the top, over which is inscribed the celebrated welcome-mat bromide ‘Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch'entrate!’ Leave behind every hope, you who enter. But it is also supplied with a city, Dis, with many houses and a wall around it, as well as other infrastructure. In Canto 15, having passed through the wood of suicides and crossed the burning river of Phlegethon, Virgil and Dante pass along a great dyke.

Ora cen porta l'un de' duri margini; e 'l fummo del ruscel di sopra aduggia, sì che dal foco salva l'acqua e li argini.Quali Fiamminghi tra Guizzante e Bruggia, temendo 'l fiotto che 'nver' lor s'avventa; fanno lo schermo perché 'l mar si fuggia;e quali Padoan lungo la Brenta, per difender lor ville e lor castelli, anzi che Carentana il caldo senta:a tale imagine eran fatti quelli, tutto che né sì alti né sì grossi, qual che si fosse, lo maestro félli. [Inferno 15:1-12]Now we passed along one of the great stony border structures, and vapours from the stream rise up, a mist to protect the river-banks and water from the flames. As the Fiamminghi (ie: the Flemish) between Wissant and Bruges, fearful of onrushing tide coming in upon them, build a dyke to repel the sea; and as the Paduans build a bulwark along the Brenta to keep their towns and castles safe when the warmer weather brings floods to Carentana: in just such a way these banks had been formed, except that the builder—whoever he was—had not made them quite so lofty or thick as those.

Here's Dorothy L Sayers’ translation:

Now the hard margin bears us on, while steam From off the water makes a canopy Above, to fend the fire from bank and stream.Just as the men of Flanders anxiously ’Twixt Bruges and Wissant build their bulwarks wide Fearing the thrust and onset of the sea;Or as the Paduans dyke up Brenta’s tide To guard their towns and castles, ere the heat Loose down the snows from Chiarentana side,Such fashion were the brinks that banked the leat. Save that, whoe’er he was, their engineer In breadth and height had builded them less great.

Who built this great dyke? Dante says it was built by the builder—a tautological answer—although he also says, of the identity of this architect, this ‘engineer’: ‘qual che si fosse’, ‘whoever he was’. Who was he? Sayers, in her note to this passage, glosses the ‘maestro’ as God, which seems wrong:—why would Dante add qual che si fosse to God’s name? Which is to say, in the sense that God is behind all creation, in one sense He is of course the maestro, the builder. But the question is: who constructed this specific structure, this dyke? Why would God, having created the hellspace, come back to add to it, improve it? To what end? For the benefit of the devils and the damned? They’re not there to have their lot improved, after all. Do we imagine God creating this structure of eternal punishment, but also adding-in various items of beneficial civic architecture? Dykes and damns, sewage systems and recycling centres, amenities and social housing?

So perhaps the devils built it, as they build Pandæmonium in Milton’s Hell. But Pandemonium is an act of pride, a great structure of marble and precious metal, gleaming in the infernal darkness visible, a fitting—so they think—place for devilish magnificence. It is, in other words, a selfish structure, and speaks to the pride and wickedness of its constructors.1 Dante’s dyke is not like this: more like an act of civic virtue, as dykes generally are. Dante specifically compares it to the dykes in the Netherlands, and in Padua: both monuments to the careful foresight and collective planning of the peoples of those territories, working to keep their communities safe from floods, and flourishing. Mark Musa, since canto 15 is concerned with the eternal punishment of ‘sodomites’, thinks that both Wissant, ‘an important port city’, and Padua were renowned as sodomitical hang-outs, but he has to confess that ‘I know of know evidence that might support this theory’ [Musa, 209]. But surely the Dutch and Paduan dykes are not in themselves monuments to buggery—somewhat the reverse, one might think—just as sodomites are, surely, pretty equally distributed amongst the general population, not concentrated in these two towns. No: the implication here is that Dante and Virgil are making their way along an impressive piece of civil engineering, a great stone barrier preventing the surrounding lands from being inundated with the flaming floodwaters of Phlegethon—pardon my alliteration (forgive that frontloaded f-phrase). This is, we can say, good work. But what place does good work, civic foresight, investment in large-scale infrastructure for the commonweal, have in Hell, of all places?

We could dismiss my questions as iterations of a ‘hobgoblins of little mind’ pedantry. But a dyke is a very specific kind of structure to find in Hell. It is not just about keeping flooding away from property; it is about fertility.

Marsh settlements expanded along the German North Sea coast and up to Ribe from the eighth- to the tenth-centuries. When the sea began to rise around 1000 so-called ‘summer-dykes’ were built. They were about 1.60m high and protected grain during growing periods, while the settlements were placed on raised platforms. By 1100 the ‘summer dykes’ began to merge together, forming longer distance coastal dykes, while in the twelfth century higher ‘winter dykes’ of 2 to 2.80 m were being built. The Dutch, who were already colonizing the deltas of the Weser and Elbe, led this spread of drainage technology. In all regions the height of dykes grew through the middle ages, and despite large losses in land due to flooding in the later fourteenth-century steady reclamation went on. [John Langdon, Grenville Astill and Janken Myrdal (eds), Medieval Farming and Technology: The Impact of Agricultural Change in Northwest Europe (Brill 1997 ), 120]

It’s like the moment when Frodo and Sam first enter Mordor, and wonder at the ghastliness of its wasted and desert extent, and Tolkien’s narratorial voice parenthetically adds that they only say so because they can’t see the extensive arable land to the far east of Mordor where the food is grown upon which orckind subsist.

In other words, the existence of this dyke opens up a sense of Hell as more than just an environment in which people passively suffer, but as a functioning topography, a place in which people—I was going to say live, but obviously that’s not the right word: but let’s say function, operate, go about their business, grow crops and build protective dykes and so on. It is, as with Heinlein’s ‘the door dilated’, to gesture suggestively at a whole worldlogic that, whilst it is not the focus of Dante’s actual text, concerned as the Inferno is only with the sinners and their punishment, but which can be extrapolated from it. Hell is populated. Some of that population are unable to do anything other than, as it might be, shriek and bleed when their living-branches are torn, or rush around, or be buried in mire. But others, when they’re not (like the false poets) having to stop to adjust to the horrible stench, or (like the hypocrites) walking about wearing cloaks of gold and lead that weigh them down, presumably getting on with things. Making and building, arranging the provision of whatever sustenance it is dead souls need. When Percy Bysshe Shelley said that ‘Hell is a city much like London’ he may have meant more than he knew.

.

Coda.

One more note on Inferno 15 and its sodomites. Sayers dedicates her translation to Charles Williams, the Inkling—that is, the poet, novelist, mythographer and teacher, who was Sayers’ friend, and the person, in the words of Barbara Reynolds, ‘whose interpretation of the allegory in terms of images (rather than of symbols) had unlocked for her the enduring truth of the work.’ Now: for Sayers, the sins Dante names throughout the Inferno are to be understood in broad terms.

When she came to write notes to her translation of Inferno she considered it essential for the sake of general, uninformed readers (for whom Penguin Classics were originally intended) to interpret the sins in terms of present-day corruptions. It is only the words that are out-of-date, she explained: the wrong-doings are unchanged. ‘Falsifiers’ are those who tamper with the commodities by which society lives, the adulterators of food and drugs, jerry-builders, manufacturers of shoddy. ‘Flatterers’ are what we now call ‘spin-doctors,’ purveyors of propaganda and sensational journalism. ‘Usurers’ are those who exploit industry, multiplying material luxuries at the expense of vital necessities. "Panders and Seducers" are those who exploit the passions of others and make tools of them. [Reynolds, ‘Fifty Years On: Dorothy L. Sayers and Dante’ Journal of the Marion E. Wade Center, 16 (1999), 4]

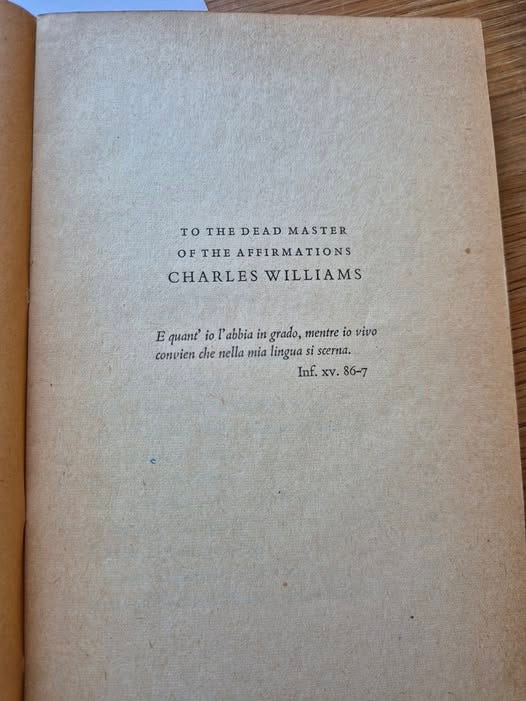

The dedication at the start of the Penguin Inferno reads:

TO THE DEAD MASTER OF THE AFFIRMATIONS CHARLES WILLIAMSE quant’ io l’abbia in grado, mentre io vivo convien che nella mia lingua si scerna.Inf. xv. 86-7

‘Dead Master’ because Williams had died in 1945.

The Italian means: ‘and how much gratitude I owe for this, whilst I live my tongue must continually give report.’ In Inferno 15 Dante meets his old mentor and teacher, fellow Florentine Brunetto Latini (c1220-94), and speaks tenderly of all he has learned from him, and how much he loves him: ‘Dante's treatment of Latini is commendatory beyond almost any other figure in the Inferno. He calls the poet “a radiance among men” and speaks with gratitude of “that sweet image, gentle and paternal, / you were to me in the world when hour by hour / you taught me how man makes himself eternal.” Dante addresses Latini with the respectful pronoun voi; Latini uses the informal tu, as perhaps was their custom when they spoke together in Florence. The portrait is drawn with love, pathos and a dignity that is more compelling given the squalor of the punishment … Dante respected Latini immensely but nonetheless felt it necessary to place him with the sodomites since such behaviour by Latini was well known in Florence at the time’ [John Sinclair]. So yes: howevermuch Dante loved Latini, the fact manifestly was: Latini was gay. Into Hell with him, then.

Is there something similar in Sayers citing these verses, from this particular bit of the Inferno, in the dedication to her translation? Charles Williams wasn’t a homosexual—was, indeed, a devout if somewhat idiosyncratic Anglican, married with a daughter. But Sayers is clear that she takes ‘sodomy’ as ‘the image of all perverse vices which damage and corrupt the natural powers of the body’, as she puts it in the notes to this section of her translation. ‘It is here, for instance, Dante would probably place drug-takers and the vicious type of alcoholics.’ The qualification that only vicious types of alcoholics would end up here is, presumably, Sayers’ sop to her husband, Oswald Arthur ‘Mac’ Fleming, who was an alcoholic, but one, we may forgive Sayers for thinking, of a harmless kind. What about Williams? Married though he was, lecture on the virtues of chastity and virginity though he did, his sexual life was not one that avoided damaging the natural powers of the body. Michael Newton:

He argued that romantic love, the force of Eros, was consecrated, and that in the lover’s heightened sense of the beloved resides the divine … C S Lewis was impressed by Williams’s wartime lecture to Oxford undergraduates on Milton’s Comus and chastity, amazed that this monkey-faced man had raised a group of young men and women to a state of wonder concerning the ineffable virtue of virginity. Knowing that he was at the time busy enthusiastically beating the bottoms of younger colleagues, students and fans somewhat dampens the wonder. But Williams isn’t the first person to praise a virtue he didn’t practise; indeed it can be argued that its absence in his own life made it particularly precious to him.

Did you say, bottoms?

Aged nearly forty, Williams fell for Phyllis Jones, the 25-year-old blonde librarian at Amen House. This was the first of a series of affairs … The relationship was that of lover and mistress, but also master and pupil. Jones fantasised that their perfect day would start with the buying of a cane in the Harrods toy department and end with Williams making good use of it. One of his letters to her declares: ‘I love you, baby! I love you, defiant witch!’

He was sexually fascinated by the buttocks, but also by the hands, which were beaten or struck as often as the behind. In his scheme for his late Arthurian poems, following occult accounts of the human frame, Williams superimposed a woman’s body over the map of Europe. The face was Britain, the hands were Italy, the vagina was Jerusalem and the buttocks were Caucasia. ‘Every woman, in order to be a goddess, must be treated like a schoolgirl,’ he once wrote to a young female acolyte, ‘but no one ought to treat her like a schoolgirl who does not admire in her a divinity; neither alone is sufficient, so the gaiety of your chastising is the gate of your glory.’ In spiritual terms, Williams stood for obedience, especially when he was the person to whom obedience was due. It’s hard to see whom he himself ever obeyed.

There would be other such relationships: an altogether more chaste version of domination with Anne Bradby (later the poet Anne Ridler); more erotic relationships with Olive Speake, and Thelma Shuttleworth, and Anne Renwick, and Joan Wallis (whom he beat in his office with an umbrella and, extraordinarily enough, a sword); and an unpleasantly brutal one with a young woman called Lois Lang-Sims. Several of these women seem to have enjoyed the rituals of punishment as much as he did, while Shuttleworth dismissed it all as ‘an uproarious joke’. Others demurred, or went along with things, only afterwards expressing anger. Lang-Sims became ill and depressed, causing Williams to speculate on his own ‘humanness’.

Sayers knew what she was doing when she appended that particular epigraph to her dedication.

We could say: Milton has a city in his Hell because Dante has a city in his Hell, and he has a city in Hell because Vergil has a city in his Hell. That, in other words, this is a matter of generic convention as much as anything. There are various things an epic ‘must’ have, including a visit to the underworld, and that underworld is structured according to the logic of epic convention: so the mortal visitor to this postmortem land must have a non-mortal guide; he must encounter the famous dead; he will see the punishments of wickedness that follow death (in Aeneid 6, Aeneas sees the terrible city of Dis and the punishments meted to malefactors, and hears Phlegyas bellowing out his warning: ‘Learn to be just and not to slight the gods. You have been warned!’)—and other things, including a pastoral and happy afterlife for the noble and virtuous, an elysium, which is not part of Dante’s business in the Inferno. This is to speak, again, to the metaphorical valence of the fantastical text: hell is urban, paradise is pastoral. But by invoking a city the text also invokes the kinds of worldbuildish hypotheticals that invite speculation: from where did the raw materials come to construct this city? What is its layout, its balance of public and private buildings, its businesses and exchanges, its entertainments, its police and emergency services? What devil-Bazalgette constructed sewers to carry away the Teufelsdrockh, and so on. It would be possible to write a version of The Underground Railroad in which all these questions, of the construction and maintenance of the actual railway, were addressed and foregrounded. It would be a very different novel to the one Whitehead actually wrote, and would not be as good, but it’s an option. And there is something exciting in the dizzying journey down the rabbit hole such questions opens for us.

Gosh, I wish I could unlearn that about Charles Williams. Interesting reflections as always, though!

Quick quibble: Crisis on Infinite Earths is a DC, not a Marvel, production. Easy mistake to make now Marvel Studios has banked so much on the multiverse.