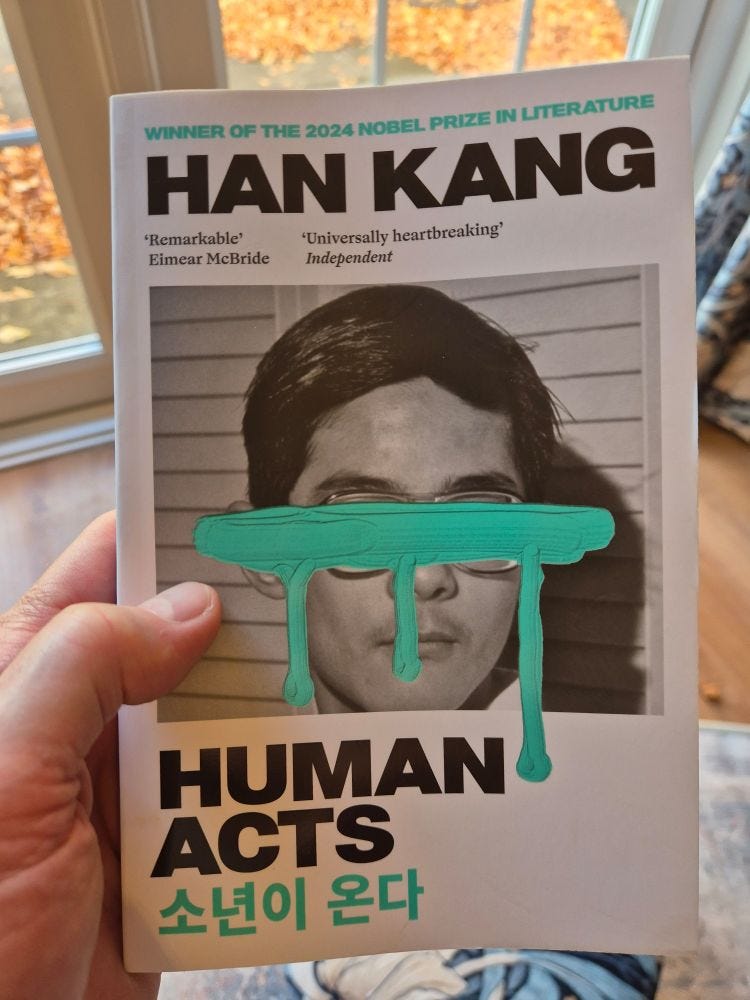

Han Kang, 'Human Acts' (2014; translated by Deborah Smith 2017)

Third in a series of ongoing posts about the Nobel Laureate's fiction

Han Kang’s Human Acts was published in 2014 under the title 소년이 온다 which means ‘A Boy Is Coming’. I don’t know if the translator altered the title because she couldn’t find a way to render it into English without importing an inappropriate sexual double-entendre, which I suppose isn’t present in Korean. The boy is called Kang Dong-ho. He is coming, in the first chapter, to a university gymnasium that is being used as a temporary morgue, filled with the dead bodies of students—killed by Korean security forces, during the May 1980 Gwangju Uprising.

The translator (Deborah Smith) furnishes a preface to explain to Western readers, who may not know, the historical circumstance. South Korea had been ruled by military strongman Park Chung-Lee since he seized power in a coup in 1961. Park had overseen the economic miracle by which South Korean had gone from ‘dirt-poor and war-shattered into a fully industrialised economic power-house’, but there had been losers as well as winners in his transformation, and especially in the south of the country there was discontent. In 1979 Park declared martial law. Then, in October, he was assassinated, by the director of his own security services. The presidency was claimed by Chun Doo-hwan, ‘another army general with strong ideas on how people should be governed,’ as Smith puts it. At this, protests broke out. In the southern city of Gwangju, student demonstrations were augmented by workers, those for whom ‘the country’s “miraculous” industrialisation had meant back-breaking work in hazardous conditions, and for whom recent unionisation had led to greater political awareness.’ Chun sent in paratroopers, to augment the police presence, and suppress the protests. Perhaps two thousand protestors were killed—the number is contested: official figures suggest a far lower number, and ‘disputing the official figures was initially punishable by arrest, and despite being far lower than the estimates of the foreign press, these have still not been revised’. Bodies were dumped, many unidentified, and Smith notes the Korean context, ‘animist beliefs and the idea of somatic integrity—that violence done to the body is a violation of the spirit/soul which animates it’.

In Gwangju part of the magnitude of the crime was that the violence done to these bodies, and the manner in which they had been dumped or hidden away, meant they were unable to be identified and given the proper burial rites by their families.

Han Kang was born and grew-up in Gwangju: her family moved to the suburbs of Seoul the year the massacre took place. Human Acts novelises the event not as a straightforward historical recreation, but obliquely, through the interwoven narratives of a number of people caught-up in it, some in 1980, others in the present day looking back: the novel’s six chapters, followed by an epilogue, move sinuously from perspective to perspective, from life to death, past to present. But throughout Han focuses not on an overview, not on the chronology of the massacre, or the tactics of protestors or security services, or history, or upon politics, or history, but upon the individual experiences of people, in the moment and afterwards, looking back.

Smith in her introduction compares the novel to Antigone, but that’s inexact. In Sophocles’ play the agon balances justification on both sides: Creon genuinely believes he is doing the right thing, in upholding the authority of the state, law and order, for the collective good, by ordering the corpses of the enemies of the state be left outside to be eaten by dogs and vultures; Antigone genuinely believes respecting the body of her dead brother, and performing funeral rites for it, is the right thing to do, despite the illegality of her actions. Both, in a sense, have right on their side; it’s the conflict between these two valid positions, dialectically interrelated (as Hegel argued in his reading of the play) that generates the tragedy.

Han’s novel isn’t like this. Human Acts doesn’t countenance any sense that the authorities might have believed they were acting properly. Chun’s argument, that the uprising was a plot by North Korea to destabilise the state and bring South Korea under communist rule, the student protestors actually North Korean agents, terrorists and revolutionaries, is treated as, simply, a ruse, as untrue in itself and known to be untrue by the torturers. For the purposes of the novel, the crackdown was actually motivated by oppression and cruelty. None of the many point-of-view perspectives in the novel derive from the perpetrators: the soldiers, interrogators, the politicians, justifying their actions and positions, or perhaps regretting what they have done. The closest the novel comes to this is a glancing reference in its fourth chapter, whose narrator ‘once met someone who was a paratrooper during the uprising.’

He said that they’d been ordered to suppress the civilians with as much violence as possible, and those who committed especially brutal actions were awarded hundreds of thousands of won by their superiors. One of his company had said ‘what’s the problem? They give you money and tell you to beat someone up, why wouldn’t you?’ [141]

This voice, doubled embedded, an unnamed soldier’s speech reported by an unnamed soldier that the unnamed narrator ‘met once’, is the only expression of what motivated ‘the other side’. Not sadism, not integral brutality, not ferocious belief in the justice of one’s cause, a kind of careless, amoral pragmatism. It perhaps looks morally otiose to suggest that the novel would be stronger if it considered both sides, but I’m not really making a moral point. I’m making a dramatic one. Focusing exclusively on the victims and their suffering limits the scope and potential of what the novel can do as fiction. Perhaps Han’s imagination was disinclined to think itself empathetically into the minds of soldiers who would shoot, torture and rape students on such a scale.

At any rate, Human Acts considers what it means to be on the receiving end of death and torture, how it violates both body and soul, how its damage goes even beyond death for the victims, how it maims the survivors and their loved ones. Above all the book is intensely focused on the somatic materiality of its topic: on bodies, on corpses that bear upon themselves, like writing, the marks of the violence that killed them, on the damaged bodies of survivors. Torture is described at length and in grisly, distressing detail. Human remains and, as per Smith’s English title, the human acts that destroyed them. Living bodies, carrying within them the consequences of their injuries, physical or emotional. The opening chapter is full of harrowing description:

Every time you pull back the cloth for someone who has come to find a daughter or younger sister the sheer rate of decomposition stuns you. Stab wounds slash down from her forehead to her left eye, her cheekbone to her jaw, her left breast to her armpit, gaping gashes where the raw flesh shows through. The right side of her skull has completely caved-in, seemingly the work of a club, and the meat of her brain is visible. These open wounds were the first to rot, followed by the many bruises on her battered corpse. [12]

Chapter 1, written throughout in the second person and present tense, concerns the titular boy, Dong-ho, coming to this temporary morgue, looking for his friend, Jeong-dae, who has gone missing during the uprising. He does not find Jeong-dae’s body, but he stays at the morgue to help out, since the two young women working there are overwhelmed by the constant arrival of more dead bodies, the stream of folk coming, looking for loved ones. Being written in the second person, you, reader, are addressed throughout and interpellated as Dong-ho:

Eun-sook would be trying to stuff a jumble of spilled, opaque intestines back inside a gaping stomach when she’d have to stop and run out of the auditorium to throw-up. Seon-ju, frequently plagued by nosebleeds, could often be seen with her head tipped back, pressing her mask over her nose. Compared with what the two women were dealing with, your own work was hardly taxing. Just as you had at the Provincial Office, you recorded date, time, clothing and physical characteristics in your ledger. On nights when the influx of new arrivals was especially overwhelming there was neither the time nor the floor space to neatly rearrange the existing order, so the coffins just had to be shoved together any old how, edge to edge. [22]

Chapter 2, told in the first-person, gives us the perspective of the friend for whom Dong-ho was looking: a corpse, murdered in the uprising. His spirit has not yet departed his corpus, and he reports his circumstance dispassionately: loaded into a truck, with other dead bodies, driven to an empty lot beside a concrete building and heaped up in a pile of corpses: ‘the body of a man I don’t know has been thrown across my stomach at a ninety-degree angle, face up, and on top of him a boy older than me, tall enough that the crook of his knees press down onto my bare feet’ [51]. The pile sits for a while, and begins to decay. Eventually soldiers come, pour petrol over it and burn it, the fire finally releasing Jeong-dae’s spirit. At the last moment we discover that the pyre also contains the dead body of Dong-ho.

Chapter 3 is set in a few years later, in 1985, and is told in the third-person. Eun-sook, who worked with Dong-ho in the gymnasium-mortuary, has survived the massacre and is now working at a publishing agency. The chapter is structured around seven slaps to the face Eun-sook received from a policeman, interrogating her over an ‘illegal’ dramatic performance, not approved by the Korean censor’s office, that memorialises the massacre.

Chapter 4 ‘The Prisoner’ is set in 1990, and is written in the first-person. The unnamed narrator recalls being arrested in 1980 and locked in a cell with another boy, Kim Jin-su, a friend of Dong-ho’s. The boys are repeatedly tortured, the novel not stinting any of the hideous details: having a biro jammed repeatedly into the flesh between his fingers (‘jammed into exactly the same space every day … a mess of blood and watery discharge: later it got bad enough that you could actually see the bone, a gleam of white amongst the filth’); rifle butts to the face, ‘the hairpin torture, where both arms were tied behind the back and a large piece of wood inserted between the bound wrists and the small of the back; water boarding; electric torture’. Eventually the two boys are sentenced to prison, but then released on amnesty. The narrator is looking back on these experiences ten years later; neither he nor Kim have recovered, physically or mentally, and on the tenth anniversary of the uprising Jin-su commits suicide.

Chapter 5 concerns Seon-ju, who had been a factory girl in Gwangji, and had worked in the morgue with Eun-sook and Dong-ho before being arrested and tortured savagely: the assault on her resulted in uterine bleeding and clots that rendered her unable to have children. She survived the experience, and in this chapter, in 2002, is working as an activist, transcribing reports, recordings and video-footage related to the massacre. She has been interviewed by an academic, and portions of her interview punctuate the . The chapter is again written in the second person, so ‘you’ are interpellated as Seon-ji. The sixth chapter is set in 2010: a soliloquy by Dong-ho's mother, her memories of her son, her grief.

In the epilogue, Han Kang herself recalls her relationship to Gwangju, and the massacre, and the long shadow it cast across South Korea’s later history.

I read an interview with someone who had been tortured; they describe the after-effects as ‘similar to those experienced by victims of radioactive poisoning.’ Radioactive matter lingers for decades in muscle and bone, causing chromosomes to mutate. Cells turn cancerous, life attacks itself. Even if the victim dies, even if they body is cremated, leaving nothing but the charred remains of bone, that substance cannot be obliterated. [215]

In chapter 4, Jin-su has a related observation: remembering Dong-ho, he ponders ‘what is this thing we call a soul? Just some non-existent idea? Or something that might as well not exist?’ He goes on:

Or, no, is it like a kind of glass?

Glass is transparent, right? And fragile. That’s the fundamental nature of glass. And that’s why objects that are made of glass have to be handled with care. After all, if they end up smashed or cracked or chipped then they’re good for nothing, right, you just have to chuck them away.

Before, we used to have a kind of glass that couldn’t be broken. A truth so hard and clear it might as well have been made of glass. So when you think about it, it was only when we were shattered that we proved we had souls. That what we really were was humans made of glass. [137]

15th century King Charles VI of France, known as Charles Le Fou, was afflicted by what is now known as ‘the glass delusion’: ‘he wore clothing that was reinforced with iron rods, and did not allow his advisors to come near him due to his fear that his body would accidentally "shatter." He may have been the first known case of glass delusion. But for Han, it is not a delusion: it is a description of our ensoulment, of our being-in-the-world. How fragile we are.

The emphasis on our human fragility is potently realised in Human Acts—impossible to read such detailed accounts of physical torture and violation and not be affected—and the structure of the book weaves a gossamer pattern of connection, friendship, coexistence, love, in order to show how easily that web is torn and ruined. But the single-mindedness of this focus projects an implied corollary: that violence is strength, that the soldiers, the police interrogators, are the strong ones, and that seems to me wrong. It is a flattening of notions of what strength is, its possibilities. Human Acts doesn’t entirely neglect matters of collective strength, as its various characters do talk of their solidarity with other protestors, and the difference that unionisation made to workers’ lives. And the epilogue, though its focus is on the depth of the author’s haunting by the horrors of Gwangji, is set in a Korea that is a much better place than the Korea of 1980: a country no longer a dictatorship, in which workers’ conditions have improved. So protest achieved some things. But the novel itself is skewed away from this. It speaks not of the strength of those who were able to endure, however desperately, and so survive, but rather of the way the violence of their torturers succeeded, marked them forever, shattered them to glass-dust.

In Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) the torture of Winston Smith gives O’Brien a voice, a position, styles him almost as a teacher (I make this argument here). Koestler’s Darkness at Noon (1940) the torturers go out of their way to explain to Rubashov, their victim, why they are doing what they are doing: their aim is practical. Human Acts has nothing like this.

Michael Dibden voices two ‘moral objections’ to the portrayal of torture in books and films. One is that ‘to describe torture is to participate in it: to watch others suffer pain without suffering oneself is the dubious prerogative of the torturer.’ Han addresses this in Human Acts by focussing so intently upon the subjective experience of the tortured person, and saying almost nothing about the torturer—this, I have been suggesting, means a flattening of dramatic effect in the novel, a one-sidedness and attenuation, but it serves a moral purpose, in the terms Dibden mentions. His second objection is that ‘descriptions of torture don’t work, because the law of diminishing returns ensures that the reader’s sensibilities soon become dulled. But this, too, is ultimately a moral objection, for it amounts to saying that such descriptions trivialise their subject.’ So far as this is concerned, we can see Han working hard to inject variety into her telling, even though what she is telling is essentially the same thing over and over: she shifts the point-of-view, from chapter to chapter and within chapters, she moves from second-person to first-person to third person, present tense to past tense, she moves in time from 1980 to later times, from poetry to prose, from reportage to inner-monologue to symbol and visual description.

It seems like a strange thing to say about a novel so intimately involved in this large-scale political atrocity, but Human Acts is not really a political novel. It is a subjective one. It seeks to render pain without compromising or contaminating it. In The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry says:

To acknowledge the radical subjectivity of pain is to acknowledge the simple and absolute incompatibility of pain and the world. The survival of each depends on its separation from the other. To bring them together, to bring pain into the world by objectifying it in language, is to destroy one of them; either, as is the case of Amnesty International and parallel efforts in other areas, the pain is objectified, articulated, brought into the world in such a way that the pain itself is diminished and destroyed; or alternatively, as is torture and parallel forms of sadism, the pain is at once objectified and falsified, articulated but made to refer to something else and in the process, the world, or some dramatised surrogate of the world, is destroyed.

Han renders pain and the world, and attempts to do so via subjective experience, not by objectifying the one or the other. There are no statistics in the novel, no estimates as to how many died (the one exception is when the unnamed narrator of chapter 4 notes that ‘the army was provided with eight hundred thousand rounds that day. This was at a time when the population of the city stood at four hundred thousand. In other words, they had been given the means to drive a bullet into the body of every person in the city twice over’ [124]—but this datum is offered less statistically, and more for reasons of emphasis, a reiteration of the doubling excession of the violent reaction to the uprising). The narrative is repeatedly punctuated by poetry, by moments of perceived beauty: beauty in the natural world, walking in the sunshine, moments of beautiful connection between people. But above all the novel about the horror.

===

In previous substacks about Han Kang’s fiction—on 2007’s The Vegetarian, and 2016’s The White Book—I said some less than obliging things about the prose of Han’s English translator, Deborah Smith. The prose of Human Acts is better than in those titles, I think. There are occasional blots and slips, but fewer and less noticeable than in those two English versions (‘if only your eyesight was worse’ [49] is innocent of the subjunctive; ‘a multitude of shadows quivered all around, grazing my own and each other’s with soft shudders’ [65]—each other’s what? ‘In an attempt to batten down the rising tide of fear …’ [154]—but one battens down, that is closes or secures, a hatch or cover on a ship; one cannot batten down a tide). Lacking Korean, I cannot speak to the accuracy of the translation, but there have been none of the published criticisms on that score that followed the appearance of The Vegetarian. Mostly the English here is effective, well-rendered, and expressive. That said, Han Kang’s English publisher is not going with Smith for her most recent novel, 작별하지 않는다 (‘Don’t say goodbye’) which appeared in Korea in 2021. It is currently being translated into English by Emily Yae Won and Paige Aniyah Morris and will be published in 2025 under the title We Do Not Part.