Han Kang, 'The White Book' (2016; translated Deborah Smith, 2017)

Another in an ongoing series of posts on the work of the latest Nobel Literature laureate

The White Book is brief, 45,000 word or so: a novella. It consists of a string of mini-essays, most of which are half a page or a page long, and none of which are longer than three pages: an itinerary of multiple whitenesses. In Korean the title of the work is just 흰 (huin, white), but the translator has given us the steer that this is a white book. And so it is. In 1968 the Beatles released The White Album—with that lovely ironic pun in the title, as if the songs in this ‘album’ (a word, like albumen, or the white-cliffs-defined nation-name Albion, that comes from the Latin albus, white) are all colourless and blanched, when in fact they are extraordinarily varied and colourful: rock songs, ballads, quirks, satirical pieces, country-and-western, experimental sound collages, blues, ska, music hall, surf rock and proto-metal. Han’s novel is not like this—not, that is, defined by its variety. It is designedly blanched and monotous and repetitive slow to read despite its brevity, a snow-blindness of sameness to which a number of grainy black-and-white photographic images have been added, a woman holding a white object, or hunched over a blank sheet of artist’s paper.

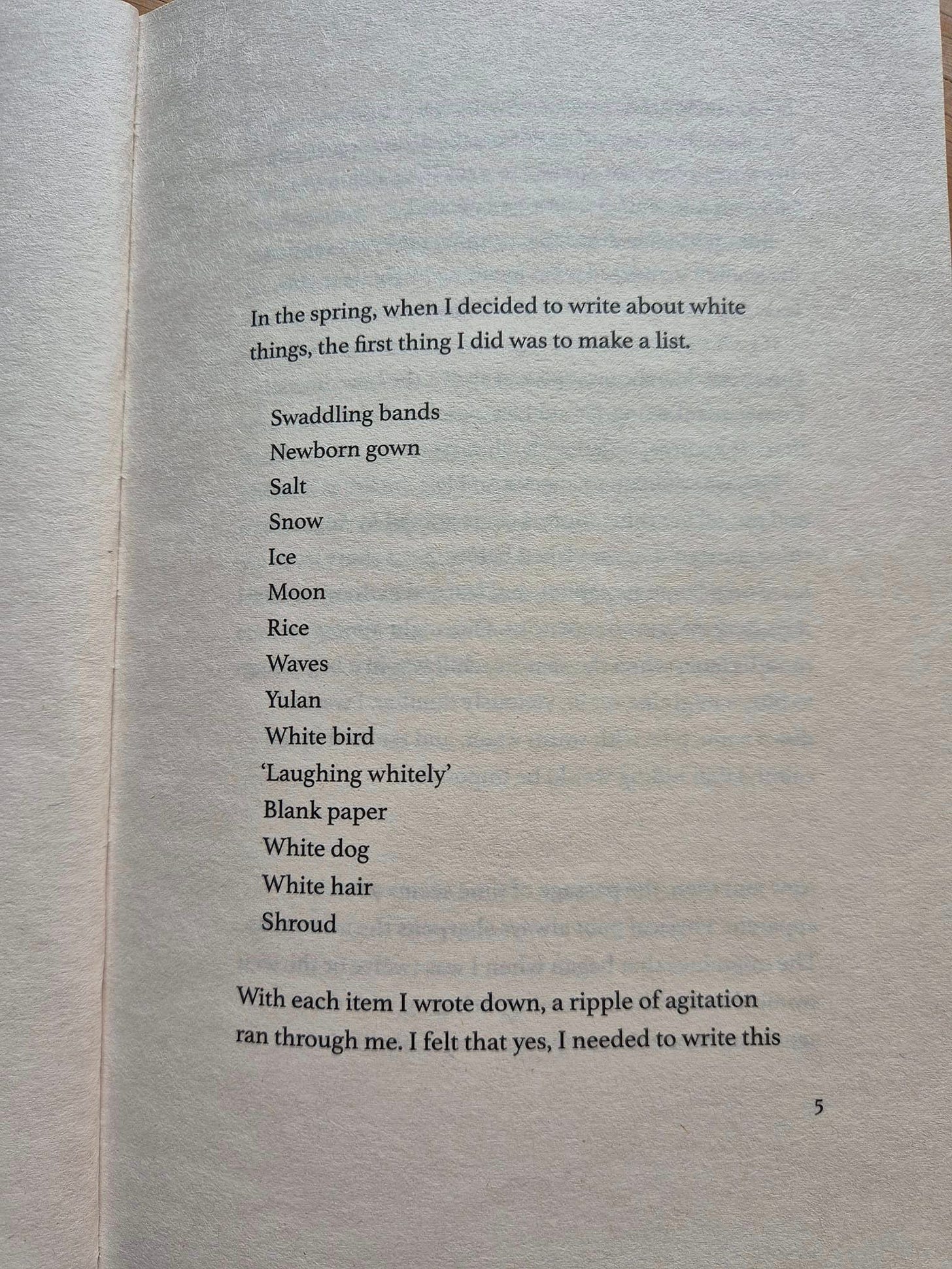

We start with a list, through which the book assiduously goes on to work:

The penultimate item, there, records that, in Korean, 희다 (huida) means ‘of colour’ to be white, and ‘of hair’ to be grey. Sections discuss inter alia snow-flakes falling on clothing, the granularity of sugar, what happens when a person renting an apartment repaints her front door with white paint, ‘the dazzling place within a white cabbage, the precious young petals concealed at its heart’. This white thing, that white thing. In amongst all this, a sense, just about, of a central character emerges: an unnamed, presumably Korean, woman who has travelled to a European city to live for a while, where she is renting an apartment. This woman considers the history of the city in which she has rocked up, where decades earlier the Nazis occupied and were resisted, and where Jews were murdered in large numbers:—it is presumably Warsaw, although the city is never named. The narrator also considers Hiroshima, or Nagasaki (it’s not clear) as a city completely destroyed and then wholly rebuilt: death as the blank slate upon which humanity re-writes.

The narrator tells us about her older sister, who died less than two hours after being born, and whom she never knew. What happened is that her mother, home alone in a house ‘in an isolated part of the country’, gave birth unexpectedly:

My mother’s due date was still far off, so she was completely unprepared when, one morning, her waters broke. There was nobody around. The village’s sole telephone was in a tiny shop by the bus stop—twenty minutes away. My father wouldn’t be back from work for another six hours.

The desperate mother does the best she can: sterilizing some scissors to cut the umbilical cord, wrapping the baby up, trying to feed it at breast. She says to the baby: ‘for God’s sake don’t die’. But the baby does die, and passes into the whiteness. The White Book’s narrator is haunted by this absence.

This life only needed one of us to live it. If you had lived beyond those first few hours, I would not be living now. My life means yours is impossible. Only in the gap between darkness and light, only in that blue-tinged breach, do we manage to make out each other’s faces.

The baby’s face, her mother later told her, was ‘white as a moon-shaped rice-cake’. Many other whitenesses become the objects of the narrator’s lucubrations: frost, snow, sleet; clouds; swaddling bands; salt; the foam of waves; white butterflies; a white dog; fog; blank paper. Of this last we might say: of course the whiteness of paper—the blank page, which faces every writer, and which predominates in this actual book—for much of its length there is more blank paper than ink—says something about writing, and therefore about communication. The medium upon which experience, suffering, insight, writes is the universal blankness. That white is associated, in Far Eastern cultures, with death (where Europeans dress themselves in habiliments of mournful blackness) is of course relevant.

Despite the fact that this is a story about a Korean person visiting Europe, about coming to a place where Germans persecuted and murdered Jews, one thing ‘whiteness’ in this novel doesn’t signify is race. This is not a novel about whiteness as ethnicity, although it does linger on whiteness as a literal descriptor of skin-colour, as with the dead baby’s white face. I myself published a novel about ‘whiteness’, back in 2004, though it made little mark and has fallen into the backward and abysm of neglect that awaits most novels, alas. I mention it here, in passing, only to note that my ‘whiteness’ novel, though about snow, and light, and blankness, and the blank sheet (which is to say, about the blank page) was also very much a novel about race. But for Han, race is not where her mind first goes when she thinks about whiteness.

Whiteness is blankness, purity, clarity, but also blankness and opacity, fog and the cloud of unknowing. The book does not avoid vagueness—‘I came abroad in August, to this country I’d never visited before, got a short time lease on a flat in its capital’ [6]: but why name the month but not the country or city?—and that means that it sometimes feels evasive. ‘Something’ is being constellated in this book’s album: something foggy, something chill, something cataracted. What, though?

+++

Deborah Smith’s translation tries to capture the poetic focus of Han’s writing. The English version wavers between a plain style, aiming perhaps at Korean minimalism, but achieving in English only a drabness, fatally prone to cliché (‘her words fell on deaf ears’; ‘he had been sitting the whole time, barely batting an eyelid’)—layered with sections that aim for a more purply style, gushing sometimes into fulsome overwriting (‘the wan moon wreathed with ashen and lilac light’ [75]) or cod-Biblicalism: ‘the land of ice where humans were not suffered to tread’ [58]; ‘she bears this remembrance through the streets where the sleet is falling, that is neither rain nor snow, neither ice nor water’ [61]. Straining for the poetical tone, Smith’s English stumbles, perhaps unconsciously, into iambic pentameter: a rookie error.

Why do white birds move her in a way that other birds do not? She doesn’t know. Why do they seem so specially graceful, at times almost sacred? Now and then, she dreams of a white bird flying away. In the dream the white bird is very close. [82]

Why do white birds move her in a way That other birds do not? She doesn’t know. Why do they seem so specially graceful At times almost sacred? Now and then, She dreams of a white bird flying away. In the dream the white bird is very close.

Han’s novella does combine prose and poetry, and a kind of ‘poetic prose’ is her métier; but this is too clonky a trick, too metrically regular and copybook, to work in terms of relocating Han’s idiom into English.

More, Smith’s English is often simply not competent to its fundamental business. ‘I think about the person who resembles this city, pondering the cast of their face. Waiting for its contours to coalesce’ [29]—does its, there, refer back to the person, their face, the city? If the first, then their would be more natural-sounding. The ambiguity of construction is distracting. Of a white dog, Smith has the narrator say ‘[it was] a vicious Tosa, originally bred as a fighting dog … she kept as far away from it as possible whenever she had to pass the gate, intimidated by its viciousness’ [63]. But ‘vicious’ is not the right word: the dog is being described not in terms of its vice, but its violence (‘savage’, ‘brutal’, ‘violent’ would be better). ‘There is none of us whom life regards with any partiality’ [61] is just uglily phrased. ‘She frequently forgot that her body (all our bodies) is a house of sand’ [107]—is badly put: ‘is’ agrees with ‘her body’ but not the plural ‘all our bodies’, thrustingly inserted as a parenthesis immediately before it; and the shift in tense from ‘she forgot’ to ‘is’ lands awkwardly. ‘… are houses of sand’ would be less grammatically delinquent, though still ungainly. Better would be to restructure, to avoid the trip-up: ‘She frequently forgets that, like all our bodies, her body is a house of sand’

Han’s prose is comitted to precision, a style dedicated to specificity and insight. Her writing is about seeing, really seeing, closely and accurately observing the quiddities of things: ‘I like examining and exploring details,’ she has said. ‘This idea of looking deeply at and into something is, I think, part of the realm of literature.’ What she needs in English is a prose that is always precise, always insightful, expressive and exact. This is not what Smith gives her.

This is more, I think, than me being a grammar-pedant (though I am a pedant, and a miserable one). Questions of translation, in the sense of the connections between cultures and societies, are one of the things The White Book is about: the human-rights violations of the Gwangju Uprising (the subject of Han’s Human Acts) and the Holocaust, the human experiential focus on actualities, whether west or east, language and its blanknesses at capturing the colour of actuality, especially the actuality of suffering, which is always particular and focused and intense, never a generalised quantity (a single death is a tragedy, a million is a statistic)—all this is part of what Han is aiming at in this novel. I am not convinced that she hits the target at which she aims, threads the Ulyssean line of axe-loops with her arrow, but it’s hard to tell when the English traduction of her text is so clumsily and spottily put together.

"the English traduction of her text"

Ouch.