A Visual Source for Shakespeare’s ‘Tempest’

Shakespearo Furioso

The scholarly consensus is that The Tempest, like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, is a play where Shakespeare is not simply reworking and dramatising an established story, legend, or history. Most of his plays have straightforward provenances. Not so The Tempest: here he seems to have invented his own story, a new one. Critics have proposed a number of possible sources for that creation, all of which are literary. One is William Strachey’s A True Reportory of the Wracke and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight, an eyewitness account of the 1609 shipwreck of the Sea Venture on the Bermuda coast. A problem with this, as source, is that Strachey’s account was not published until 1625, so scholars have to hypothesise that Shakespeare saw it in manuscript some time before writing The Tempest (which he probably did in 1610). Some scholars see specific verbal parallels between Strachey’s description of shipwreck and the opening scene of Shakespeare’s play, although not everyone agrees.1 There were other accounts of the loss of the Sea Venture. The Tempest is set on a Mediterranean island, not in the New World, although scholars do like to use Strachey to connect the play, obliquely, to the colonisation of America. Then there’s Montaigne’s essay ‘On Cannibals’ (John Florio had translated the essay in 1603 as Of the Canibales), which might have informed Shakespeare’s portayal of Caliban, whose name is often taken as an anagram of ‘cannibal’. But the larger lineaments of this play have not been traced to any literary source. As Anne Barton says: ‘the Bermuda pamphlets [even assuming Shakespeare read them in manuscript] did not provide him with either his characters or, except in the most general sense, his plot. Exactly where they came from is, and is likely to remain, a mystery.’2

I am here to propose a new possible source for this play, and, in a small way, to come at the whole question of sources slightly differently. A lot of the things that informed Shakespeare’s writing were literary, certainly: he would read Holinshead, or the ur-Hamlet, and then would write out his own version of those stories. But writers can take their inspiration from all sorts of places, and, whilst I can’t prove the connection, I’m going to suggest that Shakespeare took some of the prompt for his play from a couple of visual images.

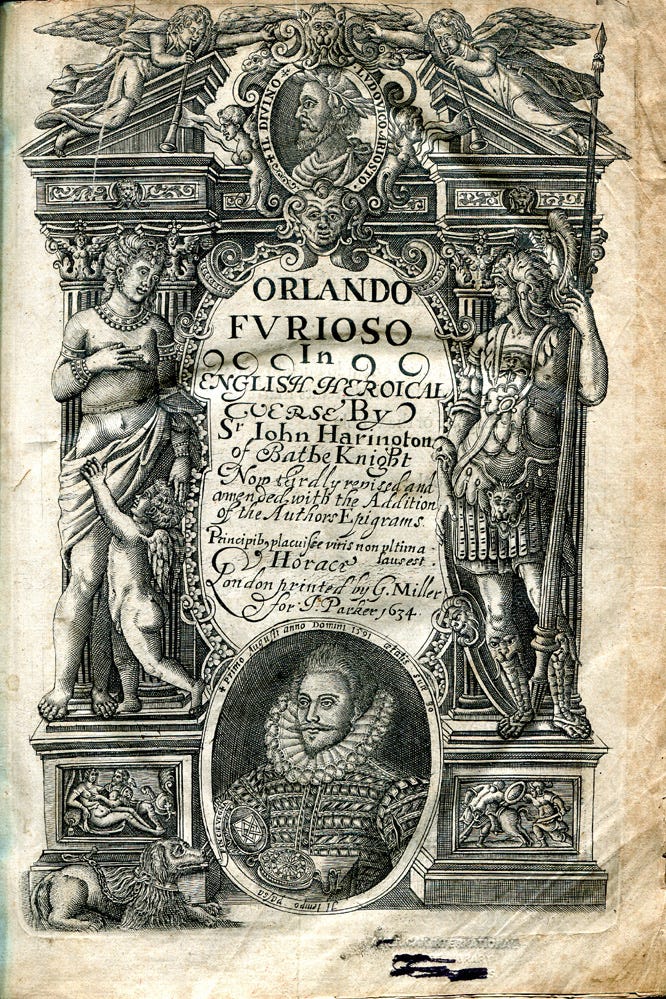

Here’s Sir John Harington, who in 1591 published his English translation of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1532)

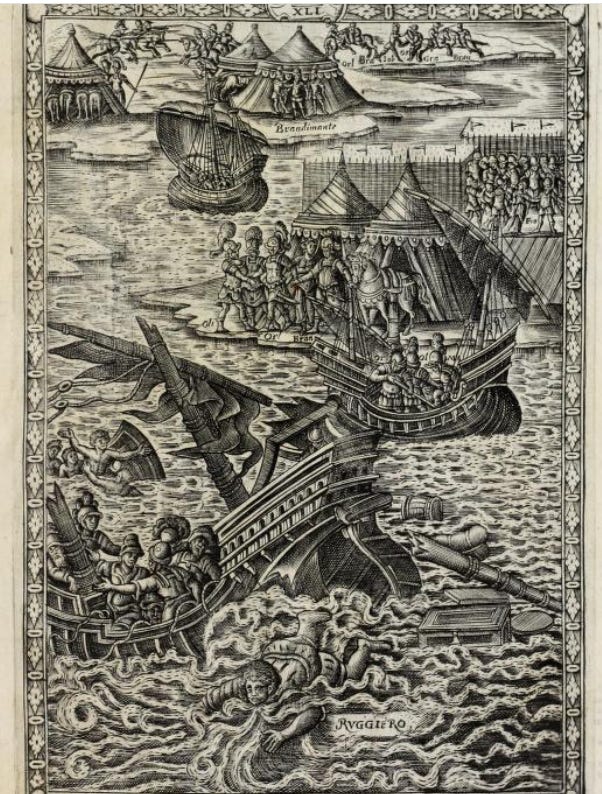

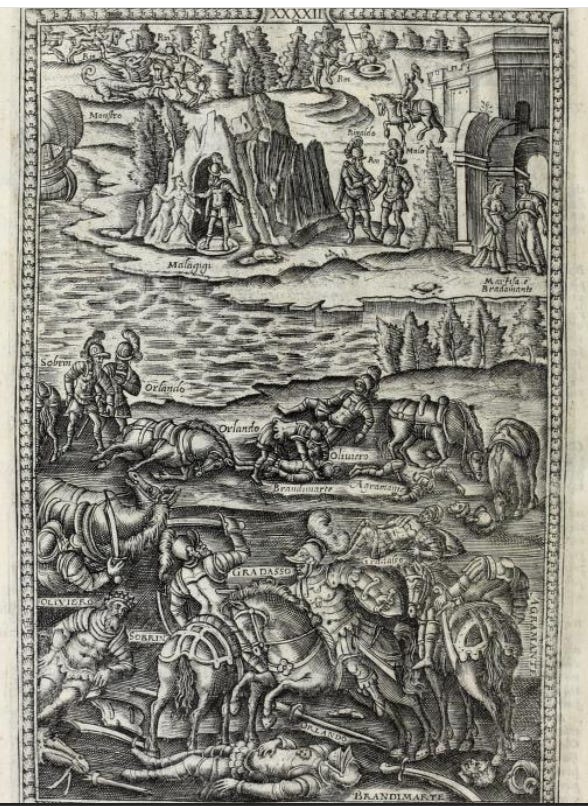

This was a large, expensive volume, and it’s not clear that Shakespeare owned, or would be likely to have purchased, a copy. But even if he only browsed the volume, in someone else’s library, or came at it some other way, I wonder if he was struck by a couple of the illustrations (themselves reworkings of the original Italian art for the poem). I picture him turning the pages of the volume. He comes across the image at the head of this post: the frontispiece to the poem’s 41st Canto. A splendid shipwreck. Ignore the armies massing for battle at the top of the picture: concentrate on the ship breaking and sinking, and Ruggiero swimming away. That might spark the germ of a story in a writer’s head: start with a ship sinking, and our hero swimming to safety. Turn the page to the next picture: the frontispiece of Canto 42:

Here the eye zeroes-in on one detail:

What does this suggest to your writerly imagination? The image is of a wizard in a cave, or cell, with a kind of monster, a bestial humanoid. It is, in fact, Malagigi (or Maugris), a wizard-knight, Rinaldo’s cousin, known for his magical skills, his ability to command spirits, and his strategic skills. The image is of him ordering one such spirit.

I think—though of course I can’t prove—that these two images sparked something in Shakespeare’s mind. The wizard suggests the character of Prospero, the coastline sketched in the engraving an island, and the beast-man Caliban (the knight in the background killing a dragon, with the legend monstro, ‘monster’, might have contributed to this). Coupled with the prior image of shipwreck, this starts to block out a storyline: a sinking ship disperses its survivors to an island. On the island is a wizard, and his beast-man familiar. This is Ariosto, so let’s make the characters Italian. And from there …?

I imagine the Shakespearian imagination starting to work upon these specific visual cues, removing them from their specific context as elements in the Orlando Furioso and starting to block out a new story that links them. Not that verbal echoes are impossible: Shakespeare presumably read Harington’s words, as well as looking at these images. Here’s the ship foundering in the storm, which Harington calls a ‘tempest’:

Now in their face the wind, straight in their back, And forward this and backward that it blows; Then on the side it makes the ship to crack Among the mariners confusion grows: The Master ruin doubts, and present wrack. For none his will, nor none his meaning, knowes To whistle, beckon, cry. It nought avails, Sometime to strike, sometime to turn their sails. [Harington’s Ariosto, 41:10]

Shakespeare’s opening scene, the wind blowing, the Master (the first character to speak in the play) fearing present wreck (‘we run our selves a ground’), him instructing the crew to ‘strike’ their sails (‘take in the toppe-sale’), the Master whistling (‘tend to th’Masters whistle’), and the ship ‘cracking’ as it sinks: ‘Mercy on us! We split, we split, Farewell my wife, and children, Farewell brother: we split, we split, we split.’ Ariosto tells us ‘no-one understood the Master’s mind’ [41:11], as Shakespeare’s royal party comes into the scene in confusion: ‘Good Boteswaine have care: where’s the Master? … Where is the Master, Boson?’ The boat sinks, at which, says Ariosto, ‘in haste/Each man therein his life strives to protect:/Of king nor prince no man takes heed nor note’ [41:18]. In Shakespeare Gonzago rebukes the Boatswain ‘yet remember whom thou hast aboord’ (meaning the king); and the mariner returns: ‘None that I more love then my selfe.’

But, honestly, none of these verbal parallels strike me as forcefully as the images. Are they a source for The Tempest?

Kenneth Muir argues that ‘the extent of the verbal echoes … has, I think, been exaggerated. There is hardly a shipwreck in history or fiction which does not mention splitting, in which the ship is not lightened of its cargo, in which the passengers do not give themselves up for lost, in which north winds are not sharp, and in which no one gets to shore by clinging to wreckage.’ Muir, The Sources of Shakespeare’s Plays (Routledge 2005), 280:

Anne Barton (ed), William Shakespeare: The Tempest (Penguin 1968), 24

Over on facebook, Colin Burrow comments: "Shakespeare certainly knew Ariosto and if he could afford Plutarch he could probably afford Harington's Ariosto. Field published Venus and Adonis as well as Ariosto so he was in a good position to negotiate a discount."

That's certainly an odd combination of images.

Re: Bermuda, Rudyard Kipling improved on Edmond Malone's suggestion about Strachey by arguing that Shakespeare might have heard about the shipwreck orally, from a surviving member of the crew. Pure speculation, but persuasively argued (in a 'letter to the editor' of 1898):

https://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/journalism/how-shakespeare-came-to-write-the-tempest/htm

See also Kipling's much later poem The Coiner, which dramatises the meeting and has Shakespeare reply to the (by now drunken) sailor to the effect of "you think you've told me a tall story, but you wait till I've finished with it".

https://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poem/poems_coiner.htm