Unthorough Thoughts on Thackeray

Can’t Say Vanity Fairer Than That

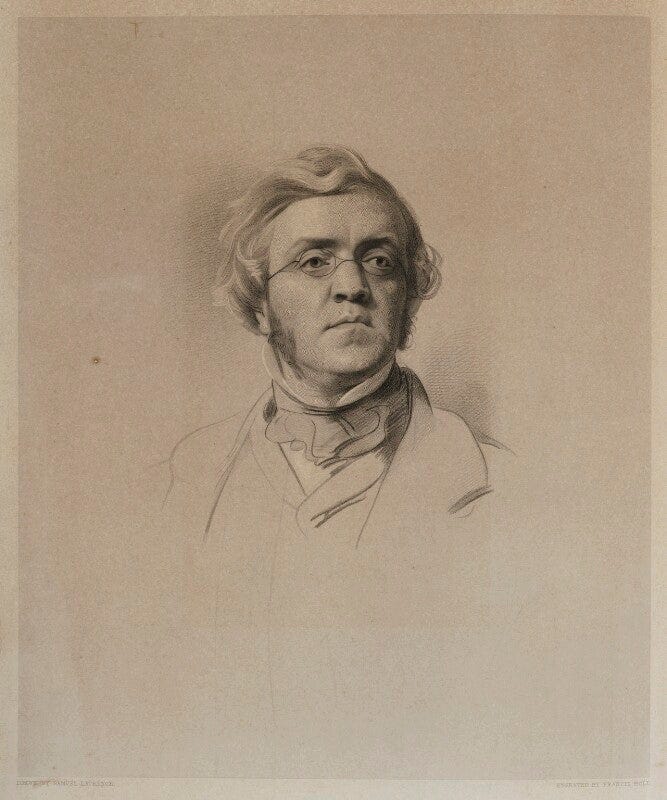

I was never Bill Thackeray’s greatest fan. Indeed, since what follows is mostly praise, I could say that a number of the reasons I used to dislike him remain for me (I mention several of these, below). But I have recently been re-reading him—and reading for the first time those of his novels to which I hadn’t got around before—and it turns out: Thackeray is great, actually. He has, I think, fallen into the shadow. People don’t read him any more, Vanity Fair perhaps excepted—and even then, I’m not sure it’s a particularly current novel. But he is worth reading.

The Victorians considered Thackeray far and away their greatest novelist (Trollope: ‘I do not hesitate to name Thackeray the first’). Dickens was seen as a popular entertainer, but it was Thackeray who was the grown-up novelist, the literary genius. Trollope thought him ‘one of the most tender-hearted human beings I ever knew, who, with an exaggerated contempt for the foibles of the world at large, would entertain an almost equally exaggerated sympathy with the joys and troubles of individuals around him’ (he added: ‘I myself regard Esmond as the greatest novel in the English language’)

I used to disagree with this judgment—in fact, I still disagree with it: Dickens, clearly, is the greater artist, as he is certainly the more enduring figure (and George Eliot, whom Trollope ranked as the second novelist of the age, is superb). I used to find Thackeray overrated, uninvolving, easy to dislike. It’s not just the familiar complaints about his lack of form and shape, though there’s truth in those: Dickens, though he serialised his big novels across twenty monthly instalments, achieved, in his later fiction, carefully constructed works of art, weaves of theme and symbol, expert pacing and plotting, character-work placed in the larger formal overview. Thackeray not so much. His big novels (Pendennis, The Newcomes, The Virginians) were serialised in twenty-four monthly chunks, and they simply spin-on, and on, monuments to an author who wanted to keep that monthly income coming in for as long as possible. The delineation of character, certainly a strength of Thackeray’s, was what the Victorians chiefly admired about him, although there was a consensus that after the creation of Henry Esmond, Becky Sharp and Colonel Newcombe, this aspect of Thackeray’s genius—making vivid, engaging, believable characters, characters who ‘live’—deserted him, and that his late novels The Virginians (1857–1859) and The Adventures of Philip (1861–1862), lacking such, are over-extended, lengthy to little purpose, virtually plotless, textual sargasso-seas. Even at his best, plot wasn’t Thackeray’s strongest suit (though Henry Esmond [1852] and Vanity Fair [1848-9] are both pretty well-plotted) but the Victorians didn’t altogether read him for his stories. They read him for his characters, his observations on modern life—sharp, perceptive, often funny—and for his style.

Coming back to him after not having read him for many years, it is this last that really stays with me. Thackeray is a really really good stylist: he’s funny, he’s witty, he is expert at observational precision and vivid turn of phrase. He is a master of English prose.

It would be a mistake to overpraise. He is not, as his great 20th-century critic Gordon Ray argued, a ‘psychological’ writer (I should add: Ray thought this a strength, not a weakness). Thackeray is not really interested in interiority, or in the development of character. Although Pendennis is often called a Bildungsroman Thackeray doesn’t really believe people change, or grow, or develop (Pen himself doesn’t: not in the way Emma Woodhouse or David Copperfield do). ‘The Thack’, as I shall not be calling him in what follows, tends to surround his main character, more fully realised and rounded, with a series of caricatures, grotesques and central-casting stereotypes, this latter a large part of his praxis as a writer, something that overlaps with his racism—for he was, really, very racist, more so than most of his peers. His novels contain more black characters than most Victorian fiction, but always in stereotypical and denigrated forms. Thackeray did not consider all men equal, and did not look at a black man and consider him a man and a brother—a phrase he several times uses in his fiction, but always sarcastically. Henry Esmond ends with the hero marrying his widowed foster-mother and moving to America, where he sells the family jewels to set himself up with a plantation: ‘our diamonds are turned into ploughs and axes for our plantations,’ he says gaily, ‘and into negroes, the happiest and merriest, I think, in all this country’—oof! In Vanity Fair, George’s father suggests the lad makes himself rich by marrying Miss Swartz, a mixed-race girl, the heir to a Jamaican fortune. He refuses: ‘“Marry that mulatto woman?” George said, pulling up his shirt-collars. “I don't like the colour, sir. Ask the black that sweeps opposite Fleet Market, sir. I'm not going to marry a Hottentot Venus.”’ [Vanity Fair, ch 21]. There are lots of minor characters of colour in Thackeray, but they all have, as it might be, bandy legs, or ‘lips like sausages’, all are mentioned in passing and figure as comic relief or casual exoticism. To read Thackeray is to realise that mid-Victorian Britain was by no means mono-racial, that it was populated by a wide range of ethnicities and peoples; but one would not read Thackeray for any insight or humanity regarding those differing ethnicities.

He was, also, thoroughly anti-Semitic (the ‘mulatto woman’ George refuses, Miss Swartz, is so called because she has a Jewish grandfather; although also, of course, her surname bespeaks her colour). I shan’t produce here the dispiriting list of his many caricatured Jewish figures and (in the case of Catherine, written under the pseudonym ‘Ikey Solomon’) narrators. Dickens was also anti-Semitic, and Fagin endures as a libel against Jewry; but Dickens repented his prejudice in later life (under the influence of Jewish friends, he revised Oliver Twist, and wrote a ‘virtuous’ Jewish character, Mr Riah, into Our Mutual Friend). Thackeray never did.

Irish characters are numerous in Thackeray’s novels, but always informed by his patronising and anti-Catholic prejudices: comic relief, bogtrotting begorrahs and idiots and drunks, though he concedes that typical stereotype that, in the words of the Proclaimers, Irish girls are pretty. Thackeray was born and spent his early years in India, until he was sent back to England to Boarding School and misery, and owned a connection with the sub-continent. He liked curry (his contemporaries believed his fondness for spicy food hastened his death—a premature demise, at the age of only 52—a huge improbability, medically, when there are other diagnoses: he contracted gonorrhoea as a student and it never left him; he ate and drank alcohol to excess and never exercised). But it must be said that Thackeray did not, as similar life-history Kipling did a generation later, write rounded or sympathetic Indian characters. His working-class characters and servants are present mostly to deliver speeches in laboriously rendered common-speech, to limited comic effect (Mr. Gawler, a coal-merchant in The Newcomes: ‘and look yere, yere’s two carriages, two maids, three children, one of them wrapped up in a Hinjar shawl—man hout a livery,—looks like a foring cove I think—lady in satin pelisse … I’m blowed if I don’t put a pistol to my ’ead, and end it, Mrs. G.’ And much more in this vein. [ch 9]). He was, argued his contemporary James Hannay [in Studies in Thackeray (1869), 6] ‘too honest to draw fancy pictures of classes with whom he had never lived.’

Above all, I have always found resistible Thackeray’s knowingness, the way he repeatedly deploys a kind of strategic disillusionment, the whole ‘you may believe in human goodness and virtue, you may be an idealist, a starry-eyed innocent, but I know better: human beings are selfish, venal, unreliable, often nasty. I shall tell the truth about people, sir!’ This is also in Waugh (another unlikeable, satiric writer with a superb style) and it’s comprehensible, as a vision of the word. Thackeray’s characters are never—I think—fully evil, or monstrous, but they almost always tend to egoism, to self-delusion and selfishness, to weakness and inconsistency, they often fall away from the standards they set themselves and fail to live up to society’s expectations. We can call this ‘being more realistic’ than the heroes-and-villains of Dickens, but realism isn’t really what Thackeray is doing. He is no Zola, or Gissing. He inhabits the forms of Victorian domestic fiction in order to satirise its conventions. Which is fine, although I don’t consider it ‘more grown up’ or mature (than, say, Dickens). Indeed, it strikes me as a pretty adolescent perspective on human affairs. ‘To describe love-making,’ he says, meaning courtship, flirting, the start of a relationship ‘is immoral and immodest, you know it is.’ Do I? ‘To describe love as it really is, or would appear to you and me as lookers-on, would be to describe the most dreary farce, to chronicle the most tautological twaddle’ [Philip, ch 17]. Would it, though?

The flipside of this, and of course intimately connected to it, is the way Thackeray so often gives way to raw sentimentalism. He is prepared to choke-up in a quasi-patriotic way about the English countryside, as when Henry Esmond—raised in ‘Castlewood’ (a stately home based on Clivedon, in Buckinghamshire)—thinks back to his boyhood, now that he has, as a grown and married man, established his new home for himself in America, also called Castlewood:

The great old house stood on a rising green hill, with woods behind it, in which were rooks' nests, where the birds at morning and returning home at evening made a great cawing. At the foot of the hill was a river, with a steep ancient bridge crossing it; and beyond that a large pleasant green flat, where the village of Castlewood stood, and stands, with the church in the midst, the parsonage hard by it, the inn with the blacksmith's forge beside it, and the sign of the “Three Castles” on the elm. The London road stretched away towards the rising sun, and to the west were swelling hills and peaks, behind which many a time Harry Esmond saw the same sun setting, that he now looks on thousands of miles away across the great ocean—in a new Castlewood, by another stream, that bears, like the new country of wandering Aeneas, the fond names of the land of his youth. [Henry Esmond, ch 3]

This is pretty writing, but too misty-eyed, too soft-edged. Remember that the American Castlewood, so far from being an ancient rural idyll, is a Virginia plantation worked by slaves.

Still, re-reading I was repeatedly struck by how expert, how wittily evocative and funny Thackeray is, as a stylist. Young Henry in The Virginians, visiting England, writes back to his American relatives that he has fallen in love with Lady Maria, describing her (‘the young gentleman,’ the narrator notes, ‘did not spell at this early time with especial accuracy’) as ‘a perfect Angle’. Back in Virginia, Henry’s mother is unimpressed: ‘Pooh, pooh! my niece Maria is forty!’ she tells her family. ‘I perfectly well recollect her—a great, gawky, carroty creature, with a foot like a pair of bellows’ [Virginians, ch 16]. Bellows is a lovely stylistic touch. In Pendennis a stage-actor utters his lines (‘Hope is the nurse of life. And her cradle—is the grave!’) ‘with the moan of a bassoon in agony’ [Pendennis ch 4]. Denis Duval packs to travel to London on the stage-coach, spending a great deal of time fussing over his portmanteau, which, the novel tells us, ‘was about as large as a good-sized apple pie’ [Denis Duval, ch 5].

Mr Honeyman, a vicar, reproves the young Pendennis, as the latter embarks on his career as an author by writing a number of satirical squibs.

‘Satire! satire! Mr. Pendennis,’ says the divine, holding up a reproving finger of lavender kid, ‘beware of a wicked wit!’ [The Newcomes, ch 19].

The deflating vanity of his purple kid-gloves is beautifully brought out. Here’s a London dawn, from Philip: ‘we cheerfully breakfast by candlelight, and I have the pleasure of cutting part of my chin off because it is too dark to shave at nine o’clock in the morning’. His wife laughs, although surely ‘my wife can’t be so unfeeling as to laugh and be merry because I have met with an accident which temporarily disfigures me’. But the scene is cosy:

The fire crackles, and flames, and spits most cheerfully; and the sky without, which is of the hue of brown paper, seems to set off the brightness of the little interior scene. [Philip, ch 18]

Sky the colour of brown paper is very good. A very elderly Viscountess in Henry Esmond refuses to dress her age, ‘attiring herself like summer though her head was covered with snow’ [Esmond ch 2]—the first insatnce of that conceit, I think. Another old person, an otherwise unnamed father in Philip, used to be passionate, but is now old and fat and watching the cricket: ‘under papa's bow-window of a waistcoat is a heart which took very violent exercise when that waist was slim. Now he sits tranquilly in his tent and watches the lads going in for their innings’ [Philip, ch 17]. The bow-window of a waistcoat is both vivid and funny. You want more kid gloves? Here’s the Honourable Augustus Frederick Ringwood, Viscount Cinqbars, making an entrance:

A sallow, blear-eyed, rickety, undersized creature, tottering upon a pair of high-heeled lacquered boots, and supporting himself upon an immense gold-knobbed cane, entered the room with his hat on one side and a jaunty air. It was a white hat with a broad brim, and under it fell a great deal of greasy lank hair, that shrouded the cheek-bones of the wearer. The little man had no beard to his chin, appeared about twenty years of age, and might weigh, stick and all, some seven stone. If you wish to know how this exquisite was dressed, I have the pleasure to inform you that he wore a great sky-blue embroidered satin stock, in the which figured a carbuncle that looked like a lambent gooseberry. He had a shawl-waistcoat of many colours ; a pair of loose blue trousers, neatly strapped to show his little feet: a brown cut-away coat with brass buttons, that fitted tight round a spider waist; and over all a white or drab surtout, with a sable collar or cuffs, from which latter on each hand peeped five little fingers covered with lemon-coloured kid gloves. [Philip, ch]

I’d say ‘… if you wish to know how this exquisite was dressed, I have the pleasure to inform you that …’, here, is superfluous, Thackeray not trusting that his description was doing the job of conveying the personality of the individual on its own, though I think it does. But this is lovely description: the emerald pinned to his cravat looking like ‘a lambent gooseberry’; the spider (rather than wasp) waist, the cod-Josephian ‘waistcoat of many colours’. [Philip, ch 8].

The style is not just about the pleasure of observational precision. It captures affect, and Thackeray is often genuinely touching. In The Newcomes, Clive is obliged to listen to a tedious sermon by his backstabbing cousin, Barnes Newcome: but his attention is caught by beautiful young Ethel, sitting across from him. The context here is that he should have married Ethel years before, and knows he should have, but that he blew his chance—chasing after the wrong woman—and now considers her irretrievably lost.

Clive Newcome was not looking at Barnes. His eyes were fixed upon the lady seated not far from the lecturer—upon Ethel, with her arm round her little niece’s shoulder, and her thick black ringlets drooping down over a face paler than Clive’s own … Clive saw and heard as he looked across the great gulf of time, and parting, and grief, and beheld the woman he had loved for many years. There she sits; the same, but changed: as gone from him as if she were dead; departed indeed into another sphere, and entered into a kind of death. If there is no love more in yonder heart, it is but a corpse unburied. Strew round it the flowers of youth. Wash it with tears of passion. Wrap it and envelop it with fond devotion. Break heart, and fling yourself on the bier, and kiss her cold lips and press her hand! It falls back dead on the cold breast again. … Do you suppose you are the only man who has had to attend such a funeral? You will find some men smiling and at work the day after. Some come to the grave now and again out of the world, and say a brief prayer, and a “God bless her!” With some men, she gone, and her virtuous mansion your heart to let, her successor, the new occupant, poking in all the drawers and corners, and cupboards of the tenement, finds her miniature and some of her dusty old letters hidden away somewhere, and says—Was this the face he admired so? Why, allowing even for the painter’s flattery, it is quite ordinary, and the eyes certainly do not look straight. Are these the letters you thought so charming? Well, upon my word, I never read anything more commonplace in my life! See, here’s a line half blotted out. Oh, I suppose she was crying then—some of her tears, idle tears—Hark, there is Barnes Newcome’s eloquence still plapping on like water from a cistern—and our thoughts, where have they wandered? far away from the lecture—as far away as Clive’s almost. [Newcomes, ch 46]

Geoffrey Tillotson quotes this passage in its entirety (what I quote here is part of a much longer section) as, he says, an example that Thackeray developed a kind of ur-stream-of-consciousness style of prose that went on to influence James Joyce and Woolf—which is not impossible—although what leaps out at me here is the way the narrator describes Barnes ‘plapping on like water from a cistern’, which is just wonderfully put.

The first amour passionelle of young Pendennis’s life is the Irish actress, Miss Fotheringay (real name: Milly Costigan): ‘her hair was blue-black, her complexion of dazzling fairness. Her eyes were grey, with prodigious long lashes; and as for her mouth, Mr. Pendennis has given me subsequently to understand, that it was of a staring red colour, with which the most brilliant geranium, sealing-wax, or Guardsman’s coat, could not vie.’ [Pendennis ch 5]. Staring red, like a Guardsman’s coat. It looks for a time, in the story, as if Pen will marry her, though she is only a poor actress, ten years his senior; but the match is stymied by Colonel Pendennis, Pen’s uncle, who reveals to Milly and her father than Pen is, as per the novel’s titular pun, penniless. The Costigans had thought him a gentleman with £2000 a year, but in fact he has nothing. Milly herself accepts this fact with equanimity, though her choleric father, drunk in the Thackeray-stage-Irish manner, challenges the Colonel to a duel for ‘deceiving’ them about Pen’s wealth (in fact the Colonel has done nothing of the sort: Pen’s supposed wealth was all Costigan’s own fantasy). The harder part is persuading young Pen. This whole section of the novel is full of beautifully observed details: the Colonel, calling at the Costigan’s shabby lodgings to break the news of Pen’s poverty, finds Milly scrubbing her ‘ex-white satin shoes’ with breadcrumbs (breadcrumbs!) to clean them, because she ‘intended to go mad with them upon next Tuesday evening in Ophelia’ [Pendennis, ch 12]. The Colonel returns home to tell Pen that Milly has thrown him over, attempting to console him that she was not worthy to be his wife anyway: ‘what?’ (looking over the letter she’d written, breaking off their engagement) ‘a woman who spells affection with one “f”?’ [Pendennis, 13]. But of course Pen is heartbroken:

Ah! what weary nights and sickening fevers! … What a pang it is! I never knew a man die of love certainly, but I have known a twelve-stone man go down to nine-stone five under a disappointed passion, so that pretty nearly quarter of him may be said to have perished: and that is no small portion. [Pendennis, 15]

This is almost facetious: but it stops just short, on the side of funny and touching.

The moments when Thackeray invites us to chortle along with his cynicism are weaker elements in his work. The real hardships in life, he says, are not disaster or bereavement, but quotidian co-existence with women.

The great ills of life are nothing—the loss of your fortune is a mere flea-bite; the loss of your wife—how many men have supported it and married comfortably afterwards? It is not what you lose, but what you have daily to bear that is hard. I can fancy nothing more cruel, after a long easy life of bachelorhood, than to have to sit day after day with a dull, handsome woman opposite; to have to answer her speeches about the weather, housekeeping and what not; to smile appropriately when she is disposed to be lively (that laughing at the jokes is the hardest part), and to model your conversation so as to suit her intelligence, knowing that a word used out of its downright signification will not be understood by your fair breakfast-maker. Women go through this simpering and smiling life, and bear it quite easily. Theirs is a life of hypocrisy. What good woman does not laugh at her husband’s or father’s jokes and stories time after time, and would not laugh at breakfast, lunch, and dinner, if he told them? Flattery is their nature—to coax, flatter and sweetly befool some one is every woman’s business. She is none if she declines this office. But men are not provided with such powers of humbug or endurance—they perish and pine away miserably when bored—or they shrink off to the club or public-house for comfort. [Newcomes, ch 40]

This is crashing stuff, and not just for its sexism. That women are hypocrites is a theme to which Thackeray often returns—that he considers all human beings hypocrites, more or less, doesn’t lessen the sharpness with which he presses his gendered point. It is styled as light comedy, observational bantering concerning the white lies in which we all collude to enable the wheels of everyday interaction to turn, but it also, Thackeray suggests, speaks to a darker truth that relates only to women. Of Becky Sharp, smiling at her husband’s dull stories, Thackeray says:

The best of women (I have heard my grandmother say) are hypocrites. We don't know how much they hide from us: how watchful they are when they seem most artless and confidential: how often those frank smiles which they wear so easily, are traps to cajole or elude or disarm—I don't mean in your mere coquettes, but your domestic models, and paragons of female virtue. Who has not seen a woman hide the dulness of a stupid husband, or coax the fury of a savage one? We accept this amiable slavishness, and praise a woman for it: we call this pretty treachery truth. A good housewife is of necessity a humbug; and Cornelia's husband was hoodwinked, as Potiphar was—only in a different way. [Vanity Fair, 17]

It's no good trying to pass this off on Thackeray’s old granny: this is Thackeray himself, sour and suspicious, verging on misogyny. The famously virtuous Roman matron Cornelia (wife of Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus and mother of the Gracchi) ‘deceived’ her husband in wholly blameless, white-lie ways; but Potiphar’s wife cheated on her feller, or tried to, with the toothsome young Joseph. Lurking behind the rather stiff comedy of this passage is a more visceral sense of women’s erotic delinquency, the belief that they are prone to sexual infidelity—as, of course, Becky herself is, cheating on her husband with the Marquis of Steyne (who pays her £1000 for the nookie). As the 4th Earl of Castlewood, adoptive father to Henry Esmond tells him: ‘they're like that—women are—all the same, Harry, all jilts in their hearts.’

Vanity Fair is, as its subtitle tells us, a ‘Novel Without A Hero’. But this doesn’t mean that it’s a novel that repudiates heroism. On the contrary, there are several types of heroism on display: George, for all his personal failings, dies in battle at Waterloo, a military hero (the bullet-wound that kills him is in his chest not his back); Dobbin performs heroic feats of selfless love and support for Emmy, whom he loves from afar, even though she is betrothed to and afterwards marries his best friend George. Thackeray styles his novel ‘without a hero’ so as to write a book with a heroine (‘if this is a novel without a hero, at least let us lay claim to a heroine’ ch 30)—or indeed, two.

The ‘conventional’ heroine is Amelia Sedley: pretty, charming, innocent, fair, blonde, blue-eyed, pink-cheeked, ‘a dear little creature … a guileless and good-natured person’. She has been raised alongside handsome George Osborne, an army lieutenant, the godson of Amelia’s parents and, it is understood, the two shall marry. And so they do, for Amelia loves George dearly, and idolises him; although George is selfish, vain, easily influenced, improvident, has a roving eye, and is fonder of playing billiards and hanging out with his male friends than attending to his fiancée. He goes along with the idea that he shall marry Amelia but, after Amelia’s father is bankrupted and quarrels with George’s father, thinks about backing out of the engagement. Dobbin, his friend, a captain in the same regiment, persuades him to marry Amelia, because he thinks it will make her happy, and selflessly her happiness matters more to him than his own does. Dobbin, you see, is in love with Amelia, and spends the whole novel yearning hopelessly after her. George does marry ‘Emmy’ but almost immediately repents of the match, since she is a drag upon his having fun elsewhere. So he’s unhappy, Amelia is unhappy at George’s neglect and Dobbin is unhappy because he now will never have Amelia. Then the regiment is called up to fight Napoleon, whereupon George is killed. This happens about halfway through the novel; the remainder is the slow coming together of Amelia and Captain William Dobbin, a consummation delayed by Dobbin’s hesitancy, and more substantively by Amelia’s hero-worshipping of her dead husband, and her belief that to marry again would be to betray his memory. This latter obstacle is disposed of at the novel’s end, by—

—the novel’s other heroine, or anti-heroine, Rebecca Sharp. Becky and Amelia knew one another from finishing school, although Emmy comes from a well-off family and Becky is very poor (her impoverished father is hired in the school to teach art and music, although he dies; the school’s owner, Miss Pinkerton, keeps orphaned Becky on, supposedly out of charity but in fact to exploit her as a servant). Becky Sharp is one of the great pieces of characterisation of the nineteenth-century novel. Knowing poverty, she is motivated not to be poor, and with moveable morals, with a capacity for ruthlessness and a single-minded focus, she goes after money. She is aided in this by her physical attractiveness, for although she is not so good-looking as Amelia in 19th-century conventional terms—Thackeray describes her as ‘small and slight in person; pale, sandy-haired, and with eyes habitually cast down’—she possesses potent sexual allure: those down-cast eyes are green and ‘when they looked up they were very large, odd, and attractive; so attractive that the Reverend Mr. Crisp, fresh from Oxford, and curate to the Vicar of Chiswick, the Reverend Mr. Flowerdew, fell in love with Miss Sharp; being shot dead by a glance of her eyes … and actually proposed something like marriage’ [Vanity Fair ch 2]. Becky wants more than a curate though. She tries to draw in Amelia’s brother, obese dunderhead Joseph ‘Jos’ Sedley (wealthy, from his work as an imperial civil servant in India), and almost snares him: but the foolish, shy, inexperienced-with-women Jos bolts before popping the question. Becky then works as a governess for the elderly and grotesque, but again very wealthy, baronet Sir Pitt Crawley. When the old man’s wife dies he proposes to Becky, but it’s too late: she has already married Pitt’s young son Rawdon, an empty-headed cavalry officer. The outraged father cuts his son off, but Becky is not incommoded: she knows Rawdon’s wealthy aunt plans on leaving her fortune to him. This goes wrong: shocked at Rawdon marrying such a lower-class woman, the aunt instead leaves her fortune to Rawdon’s brother, the religious prig, Pitt junior. Rawdon is a braying, dim-witted fellow, but not a bad sort: big, handsome, brave, and he genuinely loves his wife.

On Napoleon’s return from Elba Rawdon is called up, as are George and Dobbin: they all travel to Brussels, taking their various wives with them. At the Duchess of Richmond's ball, George flirts with Becky, and gives her a note. We are not told at this point, though it emerges at the novel’s end, that this billet is a sexual proposition, for George wants to sleep with Becky. She doesn’t go through with this, but she is already planning her financial future. If Napoleon wins and occupies Brussels she will become the mistress of one of his marshals; if England wins, but Rawdon is killed on the battlefield she will liquidate what funds she can. Jos Seley, though not a military man, has also come to Brussels with the rest of them, and is, as we would nowadays say, ‘cosplaying’ a soldier; but when rumour says that Napoleon has already defeated Wellington and is marching on the city he panics. Becky, coolly, sells him her horses at an inflated price, and he does a runner.

Amelia is pretty, but Becky is sexy, and Thackeray conveys expertly the difference between these two things. Amelia is the woman The Victorian Novel wants you to take as your wife; but Becky is who draws you. Howard Jacobson’s first (and last good) novel Coming From Behind (1983) includes a discussion about Anna Karenina—based, I think I heard once, on an actual exchange Jacobson had at Oxford. Jacobson’s protagonist Sefton Goldberg, a polytechnic lecturer, dining in the Combination Hall of ‘Holy Christ Hall’, discusses Tolstoy’s novel with the dons. There’s a reason why it is so beloved of professors and academics, says Sefton.

‘Do I understand you to be saying,’ the Master of Holy Christ Hall queried, in a rather deliberate manner, as if for the ears of an unseen interview panel, ‘that the chief benefit of being an academic, a teacher—?’

‘Is that you get to fuck Anna Karenina? Yes,’ he said. [Jacobson, Coming From Behind, 221]

This works better for Vanity Fair, I think, than Tolstoy’s often turgid novel. Thackeray is not explicit about it—as an English author he doesn’t have the freedoms a Continental novelist might—but it is strongly implied that Becky sleeps with one of the English generals; and after the war she engages in her affair with the politically powerful Marquis of Steyne. Rawdon is imprisoned for debt. Becky has the money to be able to get him released, but wants him out of the way, so she can pursue lucrative hook-ups with the upper classes without having the negotiate her husband’s jealousy. In the end Rawdon’s sister pays the requisite, and Rawdon gets unexpectedly released, and so discovers his wife and Steyne in flagrante, or as near-to as a respectable British novelist can show. Steyne is, initially, outraged by this husbandly intrusion, and tries to bluster his way out.

He thought a trap had been laid for him, and was as furious with the wife as with the husband. ‘You innocent! Damn you,’ he screamed out. ‘You innocent? Why every trinket you have on your body is paid for by me. I have given you thousands of pounds, which this fellow has spent and for which he has sold you. Innocent, by ——! You're as innocent as your mother, the ballet-girl, and your husband the bully [that is, “pimp”]. Don't think to frighten me as you have done others. Make way, sir, and let me pass’; and Lord Steyne seized up his hat, and, with flame in his eyes, and looking his enemy fiercely in the face, marched upon him, never for a moment doubting that the other would give way.

But Rawdon Crawley springing out, seized him by the neckcloth, until Steyne, almost strangled, writhed and bent under his arm. ‘You lie, you dog!’ said Rawdon. ‘You lie, you coward and villain!’ And he struck the Peer twice over the face with his open hand and flung him bleeding to the ground. It was all done before Rebecca could interpose. She stood there trembling before him. She admired her husband, strong, brave, and victorious.

‘Come here,’ he said. She came up at once.

‘Take off those things.’ She began, trembling, pulling the jewels from her arms, and the rings from her shaking fingers, and held them all in a heap, quivering and looking up at him. ‘Throw them down,’ he said, and she dropped them. He tore the diamond ornament out of her breast and flung it at Lord Steyne. It cut him on his bald forehead. Steyne wore the scar to his dying day.

‘Come upstairs,’ Rawdon said to his wife. ‘Don't kill me, Rawdon,’ she said. He laughed savagely. [Vanity Fair, ch 53]

No need to spell out what they’re going upstairs to do. She admired her husband, strong, brave, and victorious indeed—‘When I wrote that sentence,’ Thackeray later recalled, ‘I slapped my fist on the table, and said “that is a touch of genius!”’ [Letters, 2: 352]. Hard to think of a scene in any other Victorian novel as charged with sexual intensity as this one.

Rawdon does leave his wife afterwards, expecting Steyne to challenge him to a duel; although Steyne, cannier than this, uses his government influence to have Rawdon sent away to become Governor of ‘Coventry Island’, a distant and pestilential colonial possession, capital ‘Swamptown’, whose previous governor had just died of yellow fever. Becky, solus, decamps to the Continent. Meanwhile, Dobbin is assiduously, but hopelessly, courting the widowed Amelia, failing in the face of her starry-eyed illusions about her ‘perfect’ hero-husband, and her son, also called George. This goes on, perhaps for too long, in terms of the novel’s structure and pacing, until Amelia, Jos Sedley and Dobbin, travelling on the continent, re-encounter Becky Sharp in the German spa-town of ‘Pumpernickel’. By this point in the story Becky is a reduced figure: drinking too much, scamming around, playing cards, presumably doing a bit of sex-work on the side (she seems to be up to something with young Tapeworm, ‘the son of Lord Bagwig of Tapeworm castle’). Thackeray knew that ‘Pumpernickle’ was a kind of dark sourdough German bread; it’s possible he also knew its etymology, from pumpen, ‘fart’, and Nickel, ‘rascal’. Consider: Pendennis’s best friend is called Fucker. I’m sorry, ‘Foker’, but same difference. Becky is pleased to see the Sedleys again, and immediately starts to work on Jos, now even fatter, drawing him back in. Becky then performs what amounts to a selfless act, the motivation of which is a little cloudy—perhaps she acts simply out of good feeling for her former friend, Amelia; perhaps she has kept a resentment hot that George, when alive, had played a part in blocking her original marriage to Jos, and wishes to denigrate him for that. Either way, she facilitates the novels happy, or ‘happy’, ending. Seeing that Emmy is hero-worshipping her dead husband, and that this is preventing Dobby from marrying her and making her happy, she intervenes: shows Amelia the notes George passed her on the eve of Waterloo, propositioning her. After her shock, Amelia reappraises where she is, and returns to England with Dobbin, to marry. I put ‘happy’ in inverted commas because the novel strongly implies that this consummation, so devoutly wished-for by Dobbin for so many years, will prove a disappointment. He has erected a fantasy version of Amelia in his heart, against which the reality, a pretty but vacuous and foolish woman, will not measure (as Billy Bragg sang: ‘there’s just no ignoring/You’re pretty, but you’re boring’). This seems to have been Thackeray’s intention all through. Henry George Liddell (father of Wonderland’s Alice, co-editor of the Greek Lexicon) knew Thackeray, and recorded this story:

At this time Vanity Fair was coming out in monthly parts in its well-known yellow paper covers. He used to talk about it, and what he should do with the persons. Mrs Liddell one day said, ‘Oh, Mr Thackeray, you must let Dobbin marry Amelia’. ‘Well,’ he replied, ‘he shall, and when he has got her, he will find her not worth the having.’

Jos stays with Becky in Pumpernickel. She persuades him to sign-over a portion of money to her as part of his life insurance. Then Jos dies. Did Becky kill him? His health was not good (‘he procured prolonged leave of absence from the East India House, and indeed, his infirmities were daily increasing’) but his demise is suspiciously well-timed for Becky: with the money she thereby acquires she is able to return to England and live a more-or-less respectable life. ‘The solicitor of the insurance company swore it was the blackest case that ever had come before him, talked of sending a commission to Aix to examine into the death.’ No investigation is preferred, though; so if it was murder Becky gets away with it. Some readers have baulked at the thought that Becky would turn full Tom Ripley and start bumping people off: when Andrew Davies adapted the novel for the BBC, he effectively re-wrote the ending, leaving Jos unmurdered and Becky with open-ended schemes before her. Becky-the-murderer was too extreme for him, and perhaps for many readers. John Sutherland asks ‘does Becky kill Jos?’ and answers ‘of course not’—he notes that there are no other examples in nineteenth-century fiction of a murderer getting away scot-free with their crime (in fact he identifies one exception to this rule, the obscure and odd Paul Ferroll [1855] by ‘Mrs Archer Cragg’—but otherwise he’s correct), and stresses how moralistic Thackeray could be, at the end of the day, and for all of his cynicism and irony: ‘Thackeray had been one of the main castigators of the so-called Newgate Novel — more particularly the “arsenical” variety recently made notorious by Bulwer Lytton’s Lucretia (1846), a novel which The Times called ‘a disgrace to the writer, a shame to us all’ — on the grounds that it glorified wives who poisoned husbands for gain. Thackeray had built his early career around attacks on the immoralities of Bulwer-Lytton’s fiction and its depictions of vice rewarded.’ This, though, strikes me as mealy mouthed. The question, it seems to me, is not ‘is Becky for all her failings too moral to commit murder?’ It is, rather: ‘is Becky-as-murderer sexy?’ She is explicitly styled as Clytemnestra at the end (is Clytemnestra sexy? Are you kidding?) George Lewes thought the most shocking moment in the entire novel is when Becky speculates that she could be good if only she had enough money, a position the novel itself seems to endorse:

‘I think I could be a good woman if I had five thousand a year. I could dawdle about in the nursery and count the apricots on the wall. I could water plants in a green-house and pick off dead leaves from the geraniums. I could ask old women about their rheumatisms and order half-a-crown's worth of soup for the poor. I shouldn't miss it much, out of five thousand a year.” … And who knows but Rebecca was right in her speculations—and that it was only a question of money and fortune which made the difference between her and an honest woman? [Vanity Fair, ch 41]

Lewes thought this very shocking, but Thackeray wrote to him doubling down: ‘If Becky had had 5000 a year I have no doubt in my mind that she would have been respectable’ [Letters, Il. 353]. In this, he was in effect identifying with his heroine. In 1839 he had written to his mother, who worried about his dissipations, that a mutual acquaintance was ‘good, sober and religious, a fine English squire’, adding, ‘if I had 3000 a year I think I'd be so too’ [Letters, I. 397] This is one of the secret truths of Becky, I think: that she is, in her own idiom, a kind of artist, a writer, working to create her fantasy scenes to her (material) advantage. Novelists kill people—which is to say, characters—all the time. To return to Sutherland’s claim that nowhere in the 19th-century novel does a killer get away scot-free: doesn’t Thackeray kill George right in the middle of Vanity Fair?

[A side-note: another flaw in Andrew Davies’ 19987 BBC adaptation of the novel is that it cast Natasha Little as Becky—a perfectly decent actor, but too conventionally beautiful for the role. Thackeray’s novel is clear: in many ways Becky is little and unremarkable-looking, except in two respects: her eyes, and her breasts—what the novel calls her ‘frontal development’ (the lawyers , Clump and Squills, discuss her marriage to Rawdon: ‘“What a fool Rawdon Crawley has been,” Clump said, “to go and marry a governess! There was something about the girl, too.” “Green eyes, pretty figure, famous frontal development,” Squills remarked. “There is something about her…” ch 19). If you don’t think these attributes are enough to drive heterosexual men mad with desire, you perhaps don’t know many heterosexual men. More: what’s implicit in everything Thackeray writes about Becky the sense that she actively enjoys sex: that she is in charge of her appetites, that she dresses in Blake’s lineaments of gratified desire. There is nothing sexier in a partner, of course, than this: their desire.]

+++

What of Henry Esmond, the novel Trollope, and other Victorians, considered Thackeray’s greatest work, the book Trollope considered ‘the greatest novel in the English language’? It suffers from its seriousness, I think; a self-conscious attempt by Thackeray to (as Catherine Peters puts it) ‘raise the genre of the historical novel from the depth to which it had fallen in the hands of Ainsworth, Bulwer Lytton and the prolific G P R James’, to ‘attain the status of Walter Scott … Esmond was intended to rival Waverley’). It tells its Queen Anne era story with scads of carefully researched historical detail, and a good deal of narratorial commentary on the differences between ‘then’ and ‘now’, which is not unwearisome. The plot does work towards an interesting twist: handsome, upstanding young orphaned Henry is taken in by the aristocratic Castlewood family, as a distant relative, and is attracted by Viscount Castlewood’s daughter Beatrix—a beauty, and intelligent, but not constant—moons after her, off and on, goes off to fight, under Marlborough, in the Seven Years War and then the War of the Spanish Succession; and the book ends with royalist-Tory Henry attempting to restore James to the throne, having to flee when his Jacobite plot is uncovered. At the end, having yearned after Beatrix throughout, Henry suddenly marries her mother, Lady Ravenswood, recently widowed and still young enough to give him a child, moving with her to North America (The Virginians is a kind of sequel to this novel, following the fortunes of Henry’s two grandchildren). George Eliot thought this ending ‘uncomfortable’. She wrote to Lewes: ‘the hero is in love with the daughter all through the book and marries the mother at the end!’ [Eliot, Letters, 2:67]. But the uncomfortableness is the point: Thackeray planned it so. ‘The monthly parts of Vanity Fair and Pendennis,’ Gordon Ray says, ‘were customarily dashed off a few days before they were to be published, the printer's boy sometimes waiting in the hall at Young Street to carry off his sheets as they were finished. Esmond, on the other hand, was planned as a unit, written deliberately and elaborately revised before any part of it was set up in type’ [Ray, Thackeray: the Age of Wisdom, 176].

John Sutherland summarises the significance of Gordon Ray’s huge two-volume critical biography, Thackeray: The Uses of Adversity (1955) and Thackeray: The Age of Wisdom (1958):

Ray’s biography is founded on a set of prominently declared theses. The first was that Thackeray used fiction to ‘redefine the gentlemanly ideal to fit a middle-class rather than an aristocratic context’ (‘bourgeois’ was not, for Ray, a pejorative term). Ray believed that Thackeray had experienced a transforming ‘change of heart’ and concurrent growth in moral responsibility in early 1847, as he was writing the opening chapters of Vanity Fair. The corollary was that this novel, and its successors, represent the author’s greatest achievement. Ray’s reading of Thackeray’s fiction was based on what he called ‘the buried life’ to be found in them; and in his view even the late novels, written when Thackeray was chronically sick, were works of genius. Thackeray was undervalued by posterity because, unlike Dickens, his fiction was less amenable to ‘modern theories’ – Ray meant psychologising approaches, of the Edmund Wilson kind.

This is right about Thackeray not really being amenable to psychoanalytic readings, and half-right about the ‘redefine the gentlemanly ideal to fit a middle-class rather than an aristocratic context’ idea—a cool one, but one that only applies to his 19th-century set novels, I think: Vanity Fair, Pendennis, some shorter pieces. The various 18th-century set books—the Hibernophobic Barry Lyndon, Henry Esmond, The Virginians—are not part of this project, scrupulously recreating as they do the actual aristocratic mores of their age. This makes them less interesting. And though there’s some nice comedy in The Viriginians, Esmond is so straight-faced as to be almost priggish.

It is in this novel that Thackeray coined the apothegm ‘it is not dying for one’s faith that is hard, but living for it’, one of his more famous lines. It’s humble Trooper Dick in conversation with the young, and pious, Henry Esmond:

‘The rack tore the limbs of Southwell the Jesuit and Sympson the Protestant alike. For faith, everywhere multitudes die willingly enough. I have read in Monsieur Rycaut's History of the Turks of thousands of Mahomet's followers rushing upon death in battle as upon certain Paradise; and in the great Mogul's dominions people fling themselves by hundreds under the cars of the idols annually, and the widows burn themselves on their husbands' bodies, as 'tis well known. ’Tis not the dying for a faith that's so hard, Master Harry—every man of every nation has done that—’tis the living up to it that is difficult.’ [Henry Esmond, ch 6]

Well, indeed. And there is some of the ‘I’m not in the business of presenting fables and ideals and fictions: this is reality’ Thackerayan schtick.

And now, having seen a great military march through a friendly country; the pomps and festivities of more than one German court … Mr. Esmond beheld another part of military duty: our troops entering the enemy's territory, and putting all around them to fire and sword; burning farms, wasted fields, shrieking women, slaughtered sons and fathers, and drunken soldiery, cursing and carousing in the midst of tears, terror, and murder. Why does the stately Muse of History, that delights in describing the valour of heroes and the grandeur of conquest, leave out these scenes, so brutal, mean, and degrading, that yet form by far the greater part of the drama of war? [Henry Esmond, ch 9]

This strikes the modern note: but the problem is that Thackeray more-or-less ducks it himself. His account of the Battle of Blenheim is truncated—shortly after it begins, Henry’s horse is shot out from under him, and he himself hit in the shoulder, he passes out, regaining full consciousness long after the battle is won. And his account of the Battle of Wijnendale (he calls this ‘Wyendael’) is much more concerned with the bickering of military commanders, General Webb and General Cadogen, as to which was responsible for the victory. The other famous battles of the age are mentioned only in passing (‘the gazetteers and writers, both of the French and English side, have given accounts sufficient of that bloody battle of Blarignies or Malplaquet’). Of the Duke of Marlborough, victor of Blenheim, Henry says: ‘He achieved the highest deed of daring, or deepest calculation of thought, as he performed the very meanest action of which a man is capable; told a lie, or cheated a fond woman, or robbed a poor beggar of a halfpenny, with a like awful serenity and equal capacity of the highest and lowest acts of our nature, having this of the godlike in him, that he could see a hero perish or a sparrow fall, with the same amount of sympathy for either.’ [ch 9]. But again, this insight into Malrborough as, in effect, a sociopath, however fascinating, isn’t developed in the book.

We could perhaps argue that the two ‘periods’ about which Thackeray wrote, the early 18th-century and the mid-19th, are, for him, in dialogue each with the another: Henry Esmond, who marries his mother, fathers a child who has children who in turn spread the family line, and whose stories later novels pick up. We could say that this asks a particular question, which is also the question underpinning the Big Baggy Monster Victorian novel: ‘what happens next?’ What happens after Henry marries his mother? Oedipus, the prototype of this kind of alliance, answered riddles rather than asking them, although Oedipus himself is a riddle, a question about our desire, its familial determinants, its transgressive-incestuous origins. The children of Oedipus and Jocasta develop into a variety of tragic denouements, although that is in part because our apprehension of them is exclusively filtered generically, via Attic Tragedy. Thackeray isn’t writing tragedy, and his fundamentally comic art—comic in a generic, but also in a modern-day sense of humourous, funny, witty—reconfigures the Oedipan heritage. Comedy streaked with sourness, what is sometimes (it’s not a very good phrase) ‘dark comedy’, is the tenor of the times. The ‘comedy’ of Attic Greece, if Aristophanes is reliable témoignage, was collective, communally therapeutic, often sexual, sometimes violent, concerned with the polis rather than the individual, satiric of types. Thackeray is working in the same mode, broadly—unlike Dickens, I think, whose comedy is much more personal, individual, more bound-up in idiosyncracy of particular people, and exuberance of language. Perhaps this is one of the reasons Thackeray isn’t read so much today, where Dickens is. Or we could say, humour is how Thackeray gets at tragedy. In his studies of The English Humourists of the Eighteenth Century (1848)—writers upon whom Thackeray modelled his style: Addison, Steele, Prior, Hogarth, Smollett and Fielding—he said: ‘Humour is the mistress of tears; she knows the way to the fons lachrymarum, strikes in dry and rugged places with her enchanting wand, and bids the fountain gush and sparkle. She has refreshed myriads more from her natural springs, than ever tragedy has watered from her pompous old urn.’

There’s also the question of adaptation, since radio, TV and cinema versions of ‘classic novels’ are one of the ways they remain alive in the present age. There have been myriad adaptations of much of Dickens, and complete runs of all Jane Austen, over and again, where the only Thackeray adapted is Vanity Fair (I’ve mentioned Andrew Davies 1998 BBC version; there was also a 2018 Netflix version, though it was a bit lumpen). Nobody has adapted Esmond, Pendennis, Newcomes, Virginians or Philip and it’s not likely they will. There is the unique case of Kubrick’s 1975 Barry Lyndon, of course: but this is not so much an adaptation of Thackeray’s novel as a Kubrick movie loosely connected to the 18th-century and sort-of touching on the story of Thackeray’s novel without ever ‘getting’ its main character, or the gay savagery of the book’s tone. The film is slow, beautifully shot and framed, in love with its mise-en-scène—all those authentic 1750s interiors lit only by candlelit, those double-shots and slow zooms, gorgeous landscapes, beautiful costumes, leisurely pacing and the lengthily held tension of the final duel. Thackeray’s novel, on the other hand, is a rapid satirical picaresque, rowdily contemptuous of its Irish con-man chancer protagonist, Redmond Barry (he adds the Lyndon late in the story, when he wins the Countess Lyndon, whom he browbeats into marriage, and whom he then cheats on, abuses and tyrannises). Barry thinks himself a gentleman, although he is not. He behaves very badly, whether his fortunes are good or bad, and lacks pretty much all redeeming features. Chesterton calls the novel ‘a disagreeable story’ and he’s not wrong.

This, indeed, Thackeray fully realised. “You need not read it,” he said to his eldest daughter; “you would not like it.” The villain Barry, who never realises that he is not a hero, and his foolish wife, are only in part counterbalanced by Barry’s vulgar, loving mother, who goes to him in the day of his ruin and nurses him until he dies of delirium tremens in the nineteenth year of his residence in the Fleet prison.

Earlier I said that, for all his bogtrotting drunken blusterer Irishmen in Thackeray’s novels he at least conceded that Irish girls were pretty: in Barry Lyndon he turns his turn-of-phrase against even them: of red-headed Miss Honoria Brady (23, though she claims to be 19), he says: though she considered herself beautiful, in fact she was ‘rather of the fattest, and her mouth of the widest; she was freckled over like a partridge’s egg, and her hair was the colour of a certain vegetable which we eat with boiled beef, to use the mildest term.’ Ouch. The nastiness is partly a function of Thackeray anti-Irish prejudice, on full display in this novel (a prejudice Kubrick did not share). Thackeray was English. If his oeuvre doesn’t have a specific topography, as Dickens has London, or Balzac Paris, yet he is an English novelist, with the insights and the prejudices of that ethnos. Visiting America, 1852-3, Thackeray’s hosts fed him a meal of Boston oysters. After one particularly large one, they asked how he was enjoying his meal. Dabbing at his lips with his napkin, Thackeray pronounced himself ‘profoundly grateful’ for the meal, adding: ‘I feel as if I had swallowed a small baby’. That shocked his hosts, but strikes me as an English kind of joke. In Pendennis, Pen, and his friend Warrington, meet up. They have not seen one another for a year or so. Warrington

took his pipe out of his mouth, and said, “Well, young one!” Pen advanced and held out his hand, and said, “How are you, old boy?” And so this greeting passed between two friends who had not seen each other for months. Alphonse and Frederic would have rushed into each other’s arms and shrieked Ce bon coeur! ce cher Alphonse! over each other’s shoulders. Max and Wilhelm would have bestowed half a dozen kisses, scented with Havannah, upon each other’s mustachios. “Well, young one!” “How are you, old boy?” is what two Britons say: after saving each other’s lives, possibly, the day before. To-morrow they will leave off shaking hands, and only wag their heads at one another as they come to breakfast. [Pendennis, ch 70]

‘How hard it is to make an Englishman acknowledge that he is happy!’ says the narrator, which seems to me spot-on.

I need to give him another shot. I haven't read much of him, and if he was thought of so highly in his time...

Thank you so much for your detailed and illuminating post, Adam. I have no doubt that it is infinitely more interesting and enjoyable than Thackeray's novels. I don't think I could tolerate that level of misogyny. I love Dickens - I have read Bleak House five times, Our Mutual Friend three - but I bounced off Vanity Fair twice. I will read Thackeray for research if I must, but I don't think I'll enjoy him.