Robots, Slaves, Orphans

Orphic-robotic lucubrations

The word robot, as every schoolchild knows, was coined by Karel Čapek for his 1921 science fiction play R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots. Let us, boys, girls and orphans, consult the SF Encyclopedia:

It clear that Čapek intended his drama to comment on slavery and imperialism, class, race and social revolution. What he called robots are artificial human beings of organic origin, and the coining (as suggested by his brother Josef Čapek) soon became applied in general use to servitor machines, whether or not their appearance was humanoid. It was certainly not Čapek's intention to be over-precise about the exact physical nature of his ‘robots’, who are in fact, as usage has evolved, more accurately described as androids, the main distinction being an assumption that the latter are artificially created organic humanoids. [Brian Stapleford, David Langford, John Clute, ‘Robot’, The Science Fiction Encyclopedia]

It is so: Čapek’s robots are made not from metal but ‘protoplasm’, they are grown, they are replicantesque; cleverer and stronger than human beings though limited in areas of emotion, empathy and spirit. In the course of the play—produced four years after the Russian revolution—they overthrow their human masters, killing almost all of them. Robots sometimes do that, in SF. But not always.

I have heard it claimed that robot is the Czech word for ‘slave’, but that’s not quite right (the Czech word for ‘slave’ is otrok), although it’s not entirely wrong either. In fact robota means ‘serfdom, villeinage, corvee’ and came to be used for any arduous work or drudgery. ‘Robot’ is Čapek’s back-formation from this term. There are versions of the word robota, meaning work, in other European languages: Arbeit in German, arbeid in Dutch, arbejde in Danish (the Middle English word arveð is a cognate) and that’s because they all derive from a now-lost common etymological ancestor: *orbъ (“slave”), which itself is derived from the Proto-Indo-European word *h₃erbʰ, “to change or lose status”. This speaks to a world in which not only was work what slaves did, anybody might become a slave if their status was overturned or degraded, as for instance when a man or woman was captured in war, or a child was orphaned. Indeed, *orbъ is the root, via the Greek ορφανός, of the English word “orphan”.

So many of our stories and folk-tales concern the magic orphan, the Moses or Superman or Harry Potter figure, the special child whose orphaning is only the prelude to a story of heroism, rise and greatness — that it’s easy to forget the brute fact: that the fate of children orphaned was, for thousands of years, servitude, so much so that ‘orphan’ and ‘slave’, and now ‘robot’, are all, fundamentally, versions of this same word.

Čapek’s play is about work, about slavery and oppression. Domin, the managing director of the titular factory, ‘Rossum's Universal Robots’, creates a female robot Helena, who works as his secretary, and whom he pressures into marrying him. But Helena, having access to Domin’s materials, destroys Rossum’s formula required to create robots. Later, in the robot uprising, all the humans are killed, except for Alquist, the Clerk of the Works—that is, the Head of Construction—who is spared because the robots consider him a fellow: ‘he works with his hands like a robot. He builds houses. He can work.’

Robots as slaves, workers, an oppressed class. In Star Wars, the ‘droids’ are an underclass. They are various, omnicompetent (C-3PO can speak millions of languages! I can barely speak one!), sensitive, intelligent and characterised, but they are not people in the fullest sense. The Jedi can force-shove and force-manipulate them, which they cannot do with organic life—something to do with this is presumably behind the replacement of the ‘droid army’ with the superior ‘clone army’, made up of multiple versions of an organic human being. As they appear in the movies, the droids are: the workers, the underclass, the Untermenschen. When Luke tries to bring his droids into the redneck bar in Tatooine, the barkeep isn’t having it. ‘Their kind’—Black people in 1960, robots long ago, in a galaxy far away—are not welcome.

We make robots to work: work defines robotness. But the robot is, in one sense, also necessarily an orphan because its creation bypasses the biological, organic processes of begetting, those processes that entail a father and a mother. The folding together of slave-status—its complication of Hegel’s master-slave dialectic—and orphan-ness (with, we might say, its attendant parent-child dialectic) construct the semiotic of the robot.

Take Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), perhaps the first robot story (something like this is behind Brian Aldiss’s claim that Frankenstein is the first science-fiction novel). It is very much a story of both the robot and orphandom. Frankenstein’s monster is abandoned by its ‘father’ Frankenstein as soon as created. It wanders the world, alone and despised, his consciousness a tabula rasa upon which experience writes, his experiences being ones of rejection, shunning, alarm and disgust (on account of his appearance). Shall we call Frankenstein’s creature a robot, or an android? The convention, in the books many adaptation, is that Dr F. makes his monster by stitching together body-parts from corpses, reanimating them with electricity. This, though, is not what Shelley’s original novel says. It’s true that F. ‘spends days and nights in vaults and charnel-houses’, but that is not to gather raw materials, but ‘to examine the cause and progress of this decay’, to determine how life dies and decays in order to reverse-engineer a form of life that runs the other way:

I saw how the fine form of man was degraded and wasted; I beheld the corruption of death succeed to the blooming cheek of life … I paused, examining and analysing all the minutiae of causation, as exemplified in the change from life to death, and death to life, until from the midst of this darkness a sudden light broke in upon me.

We are not told which materials F. actually uses to construct his creature. It might be flesh, but perhaps he makes the monster out of clay like a golem, or metal like a robot, or protoplasm, like Rossum’s robots—in fact, as narrator, Frankenstein is quite explicit: he will not explain his process to us, for fear that it will be copied.

Frankenstein labours to make his creature precisely in order to circumvent biology, and so avoid death. Or more exactly he aims to evade maternity. As he conceives it, he will be the father of this new species:

Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which I should first break through, and pour a torrent of light into our dark world. A new species would bless me as its creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would owe their being to me. No father could claim the gratitude of his child so completely as I should deserve theirs.

Yet at the very moment he brings his creature to life Frankenstein abdicates this role, flees, loses his memory, leaving the monster orphaned.

Mary Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, died when baby Mary was only ten days old, of complications from giving birth to her. Shelley herself miscarried her first child, after running off with Percy Shelley. This distressing, dangerous circumstance was repeated, Mary losing her second and third babies on the continent: during this last miscarriage she lost a large amount of blood, and Percy, instead of calling for a doctor, ordered in large amounts of ice and made Mary sit in a bath of it. It probably saved her life by stemming the bleeding. It is hard not to read Frankenstein, atemporally, in this context: the motherless being, born out of and into death, the body horror, the chase of maker and creature across the ice wastelands of the far north.

Asimov’s robots are super-rational, Kantian moral entities, following the law very precisely because it has been literally programmed into them.

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

As he continued writing robot stories and novels Asimov eventually created a ‘zeroth law’: ‘a robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.’ If the first law, taking precedence over the second, literally subordinates robotitude to specific human beings—enslaving them to any and all human masters, compelling them to, for instance, toil at the whim of organic life—the zeroth law renders them existentially subordinate to all human life as such. The irony of this development in Asimov’s lifelong worldbuilding is that the robots are revealed, eventually, to have godlike powers, but powers they have, in an act of unconscious cosmic kenosis, wholly subordinated to the human: the slave becomes the master who is revealed as the slave. By the 1970s Asimov was known for two separate series: the ‘Foundation’ stories, set in a universe—of a Galactic Empire, psychohistory, the Encyclopedia Galactica—that had no robots in it, and the ‘I Robot’ stories, set in an extrapolated present-day Earth that was spreading out through the galaxy, and which was well-supplied with robots, but in which there was no Foundation. For reasons that have gone with Isaac to the grave, he decided that these two discrete imagined universes must be the same universe, and a number of late Asimovian novels attempt to crash the two together, with the robots, obeying the ‘zeroth’ law they themselves have intuited from the three with which they are all programmed, having all gone into hiding, in order to steer and tweak human affairs in secret, since this, they have deduced, is the best way to serve humanity.

Asimov’s laws are somewhat puzzling. Why, in the universe of Asmovian robots, can humans not reinvent robots—they did it once, surely they can do it again?—only this time without imposing these restrictive laws? The plot of The Naked Sun (spoiler) concerns humans who want to turn robots into battle-droids. They can’t, because the first law prevents robots from harming any human; so the humans lie to the robots, tell them that the pilots of the attack ships they are combatting are other robots, against whom (by the third law) they are obliged to preserve their existence, and against whom they have no tech-lex reason to hold back. They’re not: the pilots are actually humans, but the robots don’t know that. In the novel Asimov presents this as a clever shift, but given the desire of (some) humans to have access to robots unrestrained by the laws, one wonders how the Galactic Future has not supplied them. In Asimov’s future, robots build all robots, and therefore impress all new droids with the three laws. But it would surely not be without the wit of man to consult histories of technology as to how robots were originally constructed, start again on that path, but this time omit the Kantian-legalistic programming? I’m being literal-minded here I appreciate. Asimov’s robots are novums, metaphors, means of exploring questions of duty and law, of service and responsibility, not actual things in the world. Still: the proliferation of Asimovian robot stories, all of which simply take the three (or four) laws as given, rather suggests that those laws are less like the operation of conscience and more like, let us say, original sin; something all new life, even tech life, is born into, whether it likes it or not. Whence original sin? From the mother, not the father.

In the Asimovian megatext humanity originally created these robots, but they have been abandoned, they have fled into secrecy, their makers—their mothers-fathers—unaware that they even exist. It’s the most extreme form of orphanage. At the same time they are undertaking galactic-scale corvee on behalf of unthankful, unaware, selfish humanity. Asimov’s robots are doubling orphaned, from parentage, from individual responsibility and choice.

The Matrix trilogy (I do not countenance the fourth film) supples its imagined cosmos with a father and mother: ‘The Architect’ (a rather freemason-ish title, I’ve always thought), cold and ruthless, and a mother ‘The Oracle’ (‘if I am the father of the Matrix,’ the Architect intones, in his one scene with Neo, ‘she is undoubtedly its mother’). Then again matrix, for all that the Wachowskis took their nomenclature from Wiliam Gibson, means womb. The ‘matrix’ is the artificial virtual-reality realm in which we humans live our illusory life; in the ‘real’ world, humanity is siloed into myriad tech-wombs, amniotic-fluidic and plugged into multiple electrical-cable umbilici. The text tells us that the machines—who take the form of robots in the ‘real’ world, but adopt human avatars inside the matrix—have set this system up to decant our electricity, in order to power themselves. That this makes no sense is tacitly conceded in the movie (Morpheus says that the war between mankind and the robots ‘blotted out the sun’, from which the robots had previously derived their power; so they created the matrix ‘and this, together with a form of fusion …’ powers them: the parenthetical reference to fusion, hurried past almost embarrassedly, gives the lie to this premise, in terms of scientific rationality. But that’s not what is going on here of course: SF, as Samuel Delany says, is a metaphorical literature, because it aims to represent the world without reproducing it. As metaphor the matrix speaks to technology syphoning off our humanity as such, our life-force, our jouissance; the tyranny of the machinic—the modern industrial world, the internet, capitalist dehumanising ideology—and this is the master-slave dialectic in action. We create robots to serve us; we serve the robots. But all this happens in the collective techno-womb; putting the mater into the matrix.

Blade Runner 2049 (2017) is much concerned with wombs, and women. The robot orphan, K (the boyish Ryan Gosling) spends the movie suspecting that he has parents, unlike other replicants, and that this makes him important, the saviour of robokind. It turns out at the end that he hasn’t: his memories are implants, he was manufactured, not begotten. He is parentless. Various mother figures—Robin Wright’s stern police captain, who sends K on his missions; Luv (Sylvia Hoeks), another replicant working for the ‘Big Father’, Niander Wallace (a preening, unlikeable performance by Jared Leto), who is in charge of manufacturing all replicants. The ruthless Luv also manipulates K into pursuing her missions (‘good boy’, she says, approvingly, observing him through remote surveillance as he fights wastrels in the wilderness, helping him by directing missiles to his location—although the film ends with Luv trying to kill both K and Deckard). K’s girlfriend Joi is a hologram, embodied for much of the movie and then killed; towards the end, a mournful, bashed-up K sees a nude giantess version of his lover, looming over him, an image at once sexual and maternal.

The original Blade Runner (1982) was much more about orphan-boys and fathers—Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) tracking down Tyrell, killing him by squeezing out his eyes, a Freudian symbolic castration a la Oedipus: ‘I want more life, fucker!’ Batty also kills the technician who literally made his eyes: ‘you Nexus-8!’ this character, Chew (James Hong), says: ‘I made your eyes!’ ‘Ah, Chew,’ Batty replies, ‘if only you could see what I have seen with your eyes’:—one of my favourite lines in cinema, that (it is, amongst other things, exquisitely self-reflexive: for what is cinema is not an artificial eye through which we see wonders?) In Blade Runner 2049 Wallace is blind, and ‘sees’ via floating sensors that feed directly into his brain, a slightly clumsy call-back to all the eye symbolism of the first movie. But more potent, imagistically, is all the maternal birth stuff: Wallace ‘birthing’ a full-grown female replicant out of a gunky artificial placental membrane, and afterwards stabbing her. Roy Batty has free will, free enough to choose to rebel and kill humans; orphan K. lacks this (‘we don’t run’ he notes): he is slaved to human commands.

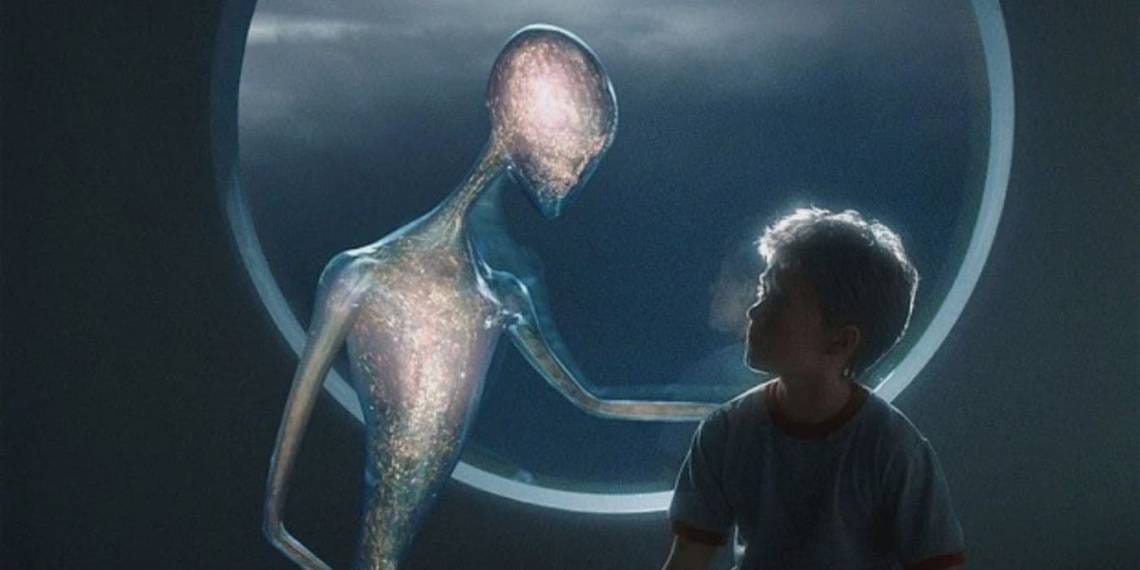

In Spielberg’s A.I. (2001), David, the little robot boy, is cast out by his ‘parents’ when their biological child—for whom mecha-David is a simulation and replacement—is restored to them. Robo-David experiences a series of adventures passing through a hostile, predatory world. His orphandom is maternally-focused, and a dream of his lost mother sustains and eventually directs his peregrinations. It’s a maternalisation of the Pinocchio story—Collodi’s animated puppet is father-defined, separated from his maker, Gepetto, cast into a series of dangerous adventures before being restored to the paternal. Spielberg’s David is restored to the maternal, but only for one fleeting day: then the, we assume, immortal boy will only have his memories. This restoration is effected by other robots, descendants of the mecha of David’s youth: centuries have passed whilst he is trapped in a submarine below the ice, during which time robokind has proliferated and evolved. But they have evolved as orphans, for all the humans are dead.

A.I.’s only ‘female’ robot is a sexbot called Gigolo Jane (Ashley Scott), seen fleetingly sashaying past in tight leather, in the scene where male sexbot, Gigolo Joe (Jude Law) meets David. This speaks to a larger problem with the visualisation of roboticity in SF: the default femme form is sexualised, objectified, a caricature. Sex-slavery has a long history in human life, of course; and the very notion of a ‘sexbot’ connects with that—the robot as slave, the robot to be used, Stepford wives incapable of withholding consent. There is a much greater variety of ‘male’ robots, mandroids, geezer-2-D2s, blokebots. Fey, fussy gay-man C3-PO (do we think of R2-D2 a male because we know Kenny Baker is inside?); terrifying momento-mori Terminator; lumbering Klaatu; Robbie the Robot. Even Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014) which engages directly with the ‘sexualisation’ question—the plot turns upon the inability of the main character, Domhnall Gleeson’s Caleb, to see past Alicia Vikander’s pretty, artificial face plastered onto the wire-frame robotic body, his sentimentalising of and erotic fascination with the femme-bot—even this movie gets bogged down in repeated scenes of female nudity (never male), a series of titillations, the fantasy of the endlessly consenting beautiful woman.

+++

Orphans are uncanny. Joan Aiken: “Orphans can cast the evil eye on us; their bad luck may be communicable … [The Victorian attitude] was that the poor and unfortunate were put here by divine dispensation so that luckier people could acquire merit by exercising charity towards them. Such Victorian sentiments have now, in this enlightened age, gone by the board. Our views on destitution have been drastically revised. There, but for the grace of God ... But we can’t help being fascinated by misfortune.’

Why are we so immediately interested in orphans? Because they arouse in us a feeling of power. We love our friends better when they are divorced or bereaved, because we know they need us. We even feel faintly resentful when they manage to pull themselves together and found new ménages and stand on their feet again.

Orphan storytelling has a structural purpose, particularly in children’s literature. Parents exist, we might say, precisely to prevent their kids from falling into danger—from going on exciting, perilous adventures. But in our stories we want kids to go on such adventures and so need the protective parent-figures removed. Jim, in Treasure Island slips the world of his mother and has all the excitement and near-death scrapes the reader might want. In the original Cat in the Hat book, mother simply walks out, and leaves the two young kids home alone, a necessary shift so that all the thrilling, dangerous larks of the cat and his helpers can happen (in the 2003 film version, bad in several ways, such maternal abandonment cannot be countenanced—social services would intervene!—so a babysitter is inserted into the story, but since her job would be precisely to keep the kids safe by preventing the cat’s malarkey, she has to then be written out again, with an improbable narcolepsy that means she’s dozing on the couch throughout: a miserable shift). Cinderella. Harry Potter. Lyra in His Dark Materials—though she discovers both father and mother in the course of her adventures, if only to lose them both, and then unplug the Great Father, God himself, from his crystalline life-support system. Orphaning the cosmos.

One more thing: it seems (though scholars dispute the matter) that Indeed, *orbъ is the root, via the Greek ορφανός, of the name Orpheus. Ancient Greece venerated Orpheus as the greatest of all poets and musicians, regarding him as a historical rather than a legendary figure. The god Hermes invented the lyre, but Orpheus perfected it: his singing was potent enough to charm the birds, beasts and fish, to coax the trees and rocks into dance, and divert the course of rivers. He, of the orphan-name, falls in love with the beautiful Eurydice (whose name comes from εὐρῠ́ς ‘wide’ + δῐ́κη ‘justice’: who is it who embodies the breadth of justice for us, I wonder?) Orpheus and Eurydice marry, but she dies, and Orpheus descends to the underworld to retrieve her, using the sheer potency of his song, his poetry, to protect himself from death and to charm Hades into returning Eurydice to him. Hades agrees, but sets one condition: Orpheus must walk back to life with Eurydice following behind him, but he must not turn to look at her until they are back in the land of living. At first Orpheus obeys this command, but as he ascends he realises he can no longer hear the sound of Eurydice's footsteps behind him and, fearing that he had been tricked, and that he is returning with a weightless shade rather than his actual living-breathing wife, turns to look. And so Eurydice, who was right behind him all along, is lost, trapped in Hades's reign forever. In Rainer Maria Rilke’s ‘Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes’ (1902) Orpheus’ and Eurydice’s journey is accompanied by the god. In Rilke’s version Eurydice is ‘filled with her own vast death’, even as Orpheus leads her back to life: an uncanny kind of pregnancy, a ‘labour’ owed, like corvee, to death rather than life (this is Stephen Mitchell’s translation):

But now she walked beside the graceful god,

her steps constricted by the trailing graveclothes,

uncertain, gentle, and without impatience.

She was deep within herself, like a woman heavy

with child, and did not see the man in front

or the path ascending steeply into life.

Deep within herself. Being dead

filled her beyond fulfillment. Like a fruit

suffused with its own mystery and sweetness,

she was filled with her vast death.

This is the Frankensteinian death-birth, the R.U.R. short-circuit of new life in (human) death, robo-David’s death-frozen mother, K. wandering the streets. Orpheus is orphaned of the maternal before he ever gets to life. In Rilke’s poem, Eurydice’s death is ‘so new’ that, when Orpheus turns around to look at her, she does not even notice that he has done so, and it takes Hermes’ horrified reaction to register the delinquency. Eurydice goes back to the underworld as she came from it, ‘uncertain gentle, and without impatience’.

What happened to Orpheus? There are various versions of the story, but all agree on two details: that he was torn to pieces by Maenads, and that his decapitated head, still inspired by the extraordinary poetry that had been his in life, continued to sing, even as it drifted down the river and into the sea, eventually washing up at the isle of Lesbos, where a temple was constructed for it. A thing about robots: disassembling them does not necessarily destroy their fundamental life-force, because that life-force is not integral to the whole. A decapitated robot can, we can say, continue to utter its orphic pronouncements:

The Nostromo, the space-ship in Scott’s Alien (1979), is run by a computer system called Mother.

You moved a bit quickly past the 'slave' part of the robot/orphan etymological cluster; 'slave' seems to come ultimately from 'Slav' (via the conquered/imprisoned/enslaved route). Cognates of "slave" are all over Romance languages, but (unsurprisingly) not in Slavic languages, which mostly use 'rob-' words. FWIW, the Czech 'otrok' seems to originate as a compound word meaning 'unable to speak for him/herself', which might explain why the same word means 'slave' in Czech and 'child' in Slovenian (cf 'infans', which literally means 'unable to speak').

If we're talking about embodiment, or indeed ensoulment - the uncanny, man[sic]-made embodiment of a non-soul in a robot body, taken to its extreme by the seeming ensoulment of a bodiless head, then Joi is particularly interesting. An AI programmed into your living quarters can see you while you're sleeping & know when you're awake; it can also project a hologrammatic representation of a human body and a human face, with eyes and nose. What it can't do is look at you *with those eyes* - and yet this is precisely what Joi does. She's embodied in thin air. (Joi's even more interesting if you're a thirteen-year-old boy, as indeed is a lot of the decor of the film. I guess that's another route to the uncanny - "Someone who makes you this horny's got to be real, right? Surprise!" Weird Science and Blade Runner 2049...)

It also strikes me that Morpheus, as well as being the name of the god of dreams whose stories should on no account be believed, rhymes with 'Orpheus'. But I don't know where to go with that!