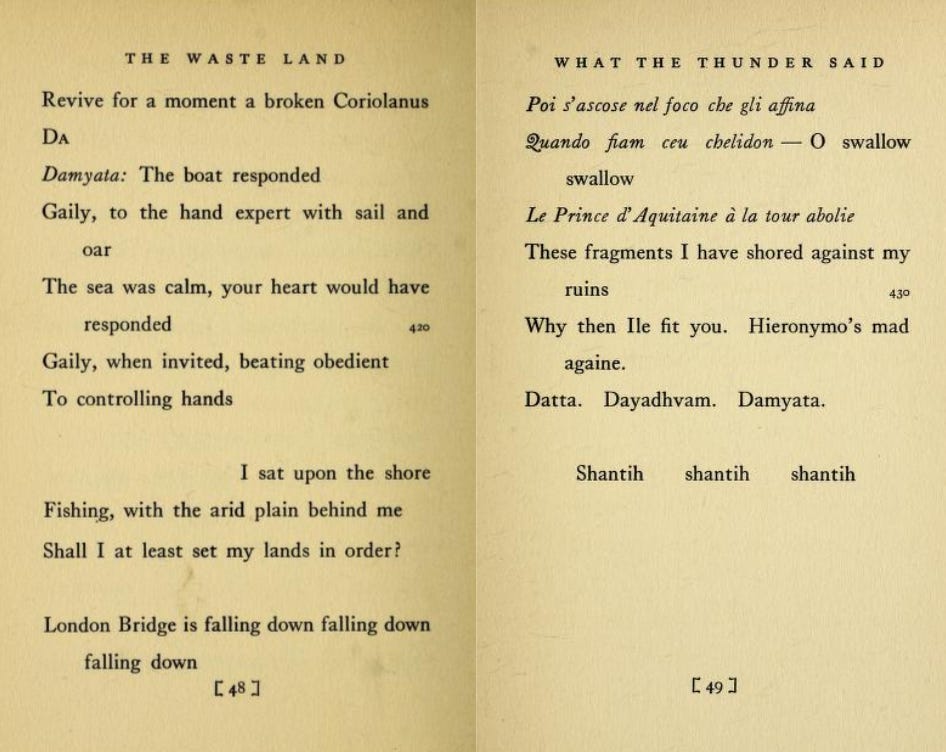

Right at the end of The Waste Land Eliot quotes Gérard de Nerval: ‘Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie’, a line from his Les Chimères sonnet ‘El Desdichado’ (1854). Here’s the sonnet:

‘El Desdichado’ Je suis le ténébreux, — le veuf, — l’inconsolé, Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie: Ma seule étoile est morte, et mon luth constellé Porte le soleil noir de la Mélancolie. Dans la nuit du tombeau, toi qui m’as consolé, Rends-moi le Pausilippe et la mer d’Italie, La fleur qui plaisait tant à mon cœur désolé, Et la treille où le pampre à la rose s’allie. Suis-je Amour ou Phébus ?…. Lusignan ou Biron? Mon front est rouge encor du baiser de la reine; J’ai rêvé dans la grotte où nage la syrène… Et j’ai deux fois vainqueur traversé l’Achéron: Modulant tour à tour sur la lyre d’Orphée Les soupirs de la sainte et les cris de la fée.

The title of the sonnet is from Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819): a mysterious knight (actually our hero Ivanhoe in disguise) arrives to fight in the lists: ‘his suit of armour was formed of steel, richly inlaid with gold, and the device on his shield was a young oaktree pulled up by the roots, with the Spanish word Desdichado, signifying Disinherited.’ Scott’s Spanish was next-to-nonexistent, and there’s no evidence that Nerval’s was any better: but in fact desdichado means ‘unfortunate’, ‘miserable’, ‘distressed’ or ‘unlucky’: not ‘disinherited’ (which would be desheredado). Perhaps Nerval knew this, or perhaps he was following Scott. No-one is sure.

There’s no lack of translations of Nerval into English (you can find various versions of this poem, ranging from serviceable to decent to pretty good) but I’ve had a go myself, below.

El Desdichado I am the Darkness, — widower, — unaligned, The Aquitaine Prince in the ruined tower: My only star death, and my lute’s star-sign Displaying the Black Sun Melancholia. In the night of the tomb you, who calmed my mind, Give me Poslippo, Italian sea, flower And so you delight this sad heart of mine: A trellis where vine and rose interbower. Am I Love, Phoebus? … Lusignan, Biron, which? My brow is still red from the queen’s planted kiss; I have dreamed in the pool where the siren swims … And I’ve twice crossed Acheron, victorious: Tuning, turn by turn, the lyre of Orpheus, The sighs of women-saints and fairies’ hymns.

My falsest step here, translation-wise, is the last word in the poem: but I stand by the rendering, since there is—it seems to me—something integrally hymnal about Nerval’s sonnet. That is my partiality with respect to this enigmatic poem. Other critics have taken it in other ways: as a symbolist, astrological work (according to Richer, ‘El Desdichado is ‘a kind of horoscope poem in which almost every word has a biographical, an astrological, and a metaphysical significance’: J. Richer, ‘Le luth constelle de Nerval,’ Cahiers du Sud, 331 (1955), 373-389). What most critics agree on is its apprehension of a state of mind of unhappiness, psychic pain—manic-depressive Nerval who lived his life by a series of eccentric spurts and dashes, often descended into misery and ended his life by hanging himself leaving a suicide note that spoke of black nights and white nights. Miranda Gill is dismissive of the story that he had a pet lobster that he used to walk, like a pet dog, up and down the Parisian streets on a silk cord instead of a leash [Gill, Eccentricity and the Cultural Imagination in 19th-Century Paris (Oxford, 2009)]—and indeed, the practicalities of such a pet would be challenging beyond what Nerval as a person was capable of maintaining, I think—though she doesn’t address the glorious statement Nerval supposedly delivered to Théophile Gautier, who mocked him for his choice:

Why should a lobster be any more ridiculous than a dog? ...or a cat, or a gazelle, or a lion, or any other animal that one chooses to take for a walk? I have a liking for lobsters. They are peaceful, serious creatures. They know the secrets of the sea, they don't bark, and they don't gnaw upon one's monadic privacy like dogs do. And Goethe had an aversion to dogs, and he wasn't mad.

But even if we, death-of-the-author-ily, detach nervy-Nerval from this poem it leaves a residue of sadness: he is tenebrosity personified; he is widowed (of what? of whom?), unconsoled and separated from the world, he is a Prince of Aquitaine in a ruined tower—the ruins, I think, speaking to this as historically belated: not the medieval kingdom in its glory, fought-over by France and England, but an epigone and merely archaeological remnant of the same, its castles now tumbledowns. His star-sign is death (as Nerval himself wouldn’t reach his 47th birthday) and the star-sign of his lute, figuring his poetic calling, is melancholy. Yet lines 5-8 make it clear that, for all that he is passing through the dark night of the soul, there is somebody else, some partner with whom this widowed and grieving man can connect, a queen, a muse, a siren, whose shared experience of swimming in the grotto-pool, whose fairy-singing sustains him. He has, he says, crossed Acheron—died—twice, and yet returned as vainqueur, victor. That’s not altogether miserable.

And Nerval’s positioning in the Waste Land: the storm has broken he drought, and we’re almost at the shantih, the peace that passes all understand: water flooding down to fill the grotto so we can swim with the siren; female-saints call to us; fairy voices carry through the air.

Looking at this again, I'm not altogether happy with how sibiliant the last line is. Tennyson used to go through his verse revising out sibilance: a process he called "kicking the geese out of the boat" (he admired Pope, but thought the opening line of "Rape of the Lock", "What dire offense from amorous causes springs", one of the ugliest in English poetry). Tennyson's verse is very rarely sibilant like this.

“the Desperado (de Nerval)”

I am the bereaved, the widower, the shadowy,

the Cathar prince of the devastated citadel:

My guiding star is snuffed, my galactic lute

carries Melancholy’s sable pentacle.

You who consoled me in the dark of the sepulcher,

give me back Posilipo & the Mediterranean,

the fragrance that enchanted my sere despair,

& that arbor where the rose & grape are intimate.

am I Cupid or Apollo?….Poe or Byron?

the kiss of some dread queen still becrimsons my brow;

I have dreamed in the grotto where the siren plashes…

& twice have I crossed Acheron victorious:

practicing in turn on the lyre of Orpheus

moans of a mystic, sobs of a dying elf.

4 26 87