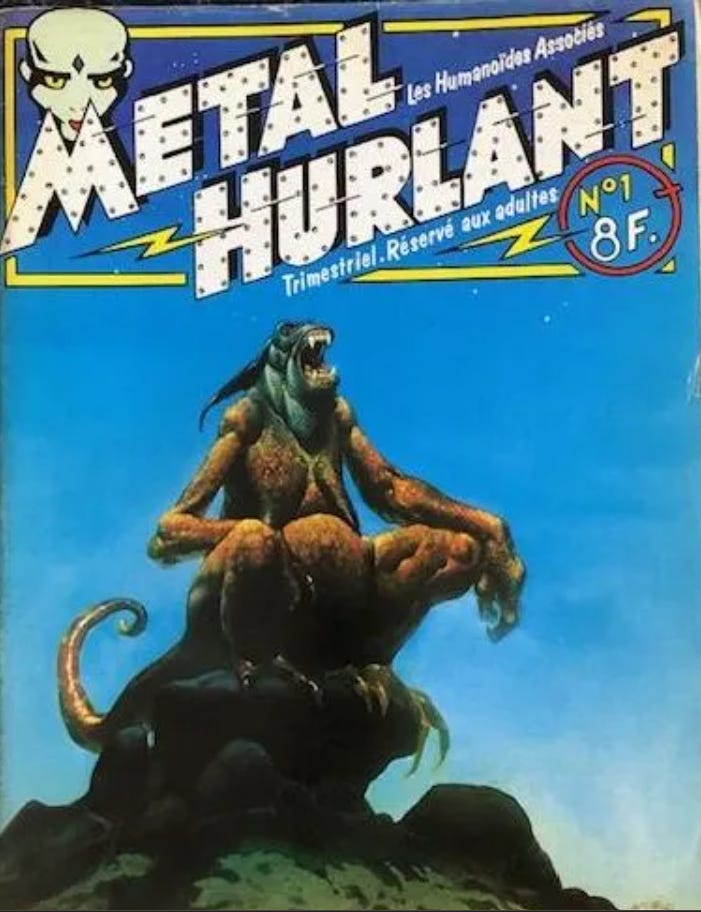

Metal Hurlant

Screaming and suggesting

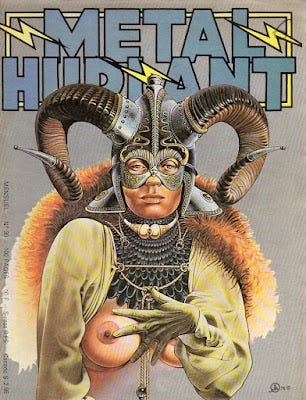

The French science-fiction magazine Métal Hurlant was founded in December 1974 by comics artists Jean Giraud (who worked as ‘Mœbius’) and Philippe Druillet, in consort with writer Jean-Pierre Dionnet and finance director Bernard Farkas. These four friends called themselves ‘Les Humanoïdes Associés’—United Humanoids—and this was the name they gave the publishing house that issued the magazine: quarterly to begin with, then, after the ninth issue, monthly. Each issue was 68-pages of text and illustration, 16 of which were full colour. It sold for 8 francs an issue—a substantial sum for a magazine in the 1970s. The magazine cover boasted, rather than warned, that it was ‘reservé aux adultes’, ‘adults only’: an indication that much of the art was sexually suggestive, and in some cases quasi-pornographic, as well as often violent and grotesque. A great many significant European science-fiction artists contributed to the magazine, and whilst it never entirely flourished, commercially—it very nearly went bankrupt in 1980, and struggled on until finally folding in 1987 (it has been resurrected a few times since then, but never to lasting success)—its reputation endures. Indeed, its influence, visually, was outsize, especially where the science-fiction of the 1980s, cyberpunk and cinematic dystopia, was concerned. In 1977 an English-language edition of the magazine began publication in the USA, under the auspices of National Lampoon. The title was translated as Heavy Metal, which makes one think of hard rock music; a poor rendering of the French title, which translates as Screaming Metal, or more literally Howling Metal, the sound of metal train-wheels breaking and screeching along metal rails—a more jarring, conceptually dissonant and less familiar referent. In terms of content the American edition reproduced the combination of dystopia, cyberpunk, dark fantasy and erotica, although the different mores of public display between the two nations resulted in some modifications to the art. Here, by Cypriot-British artist Chris Achilleos (1947-2021), is the cover for issue 39 (1979), which sat proudly on the news-stands of France.

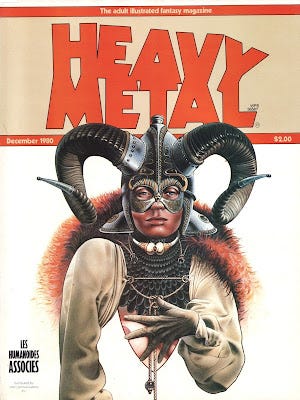

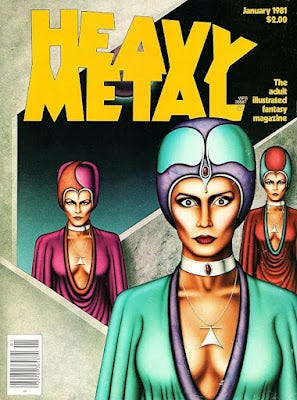

The American edition of this issue appeared in December 1980, with the some papillary censorship.

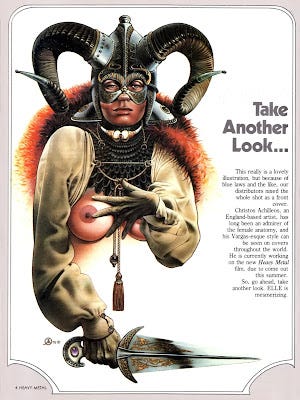

The American editors did publish the image, undoctored, inside the body of the magazine, away from the eyes of the general news-store browsers, with what amounts to an apology for their cover-bowdlerisation.

This overlap between science-fiction and titillation has always been part of SF art, of course. American aversion to the public display of a single nipple indexes what might be thought an egregious pudeur. One thinks of the national outcry during the Houston Texas, Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime show, broadcast live on February 1, 2004, when performer Janet Jackson's right breast was momentarily exposed. Though her nipple was covered by a ‘nipple shield’, the incident, called variously ‘Nipplegate’ or ‘Janetgate’, produced an enormous brouhaha and backlash, and was followed by an immediate crackdown on perceived indecency in broadcasting. It is hard to think of any equivalent incident in France.

We are talking, in other words, of differences in cultural valences: the eroticism that can be screamed in France must be more circumspectly hinted-at in America.

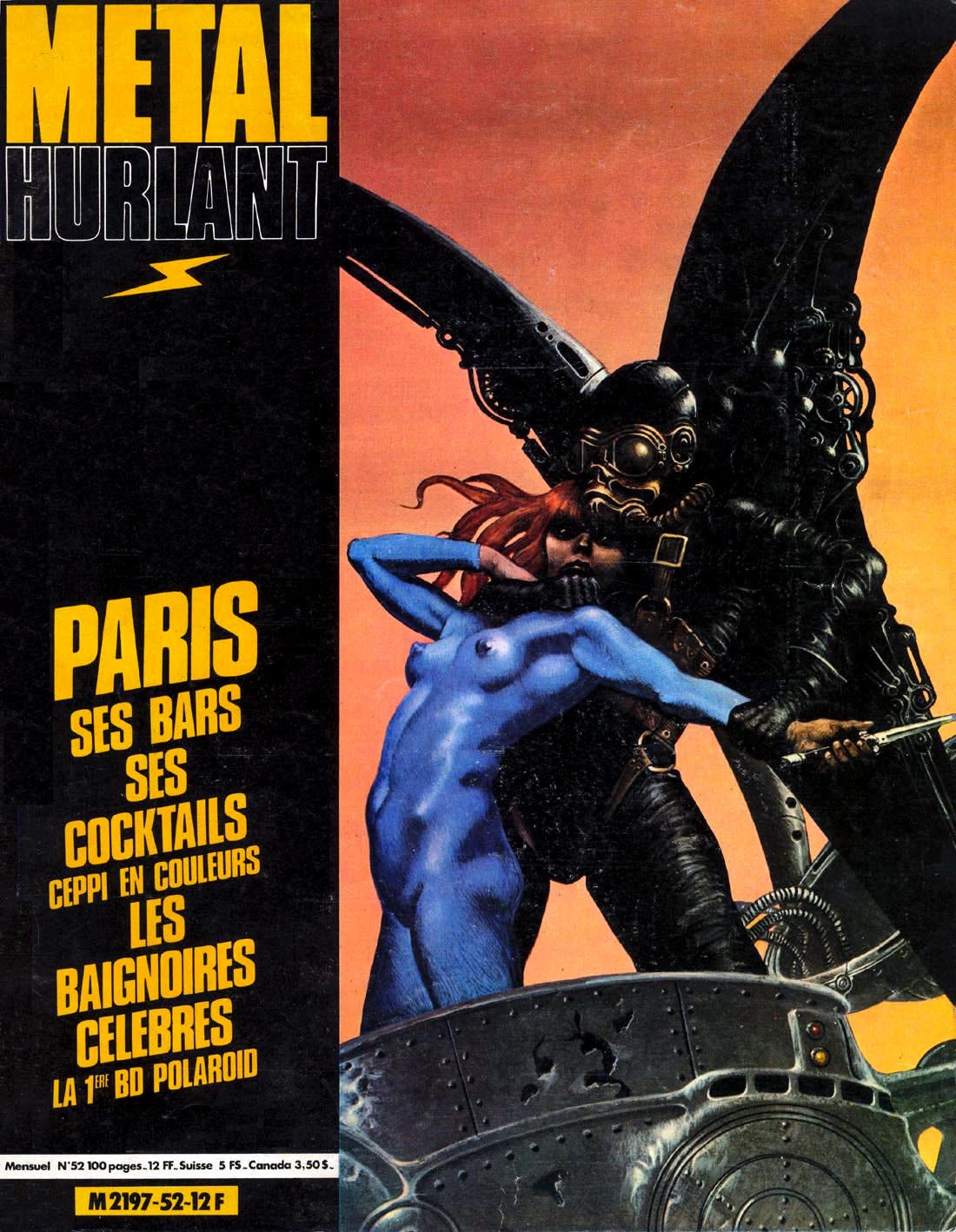

This, the American cover for January 1981's Heavy Metal, is by American artist Robert Burger (the work is entitled ‘...And One More Makes Three’). It is not sexually unsuggestive, but is restrained and, in terms of the severity of the women's expression and the stiffness of their postures, not quite what we might call lubricious. Here, by way of contrast, is the French cover that the American publishers replaced: Métal Hurlant #52 (June 1980) cover by Jean-Michcel Nicollet (born 1944).

The cover shows a leathern-winged alien creature clasping a fully naked, blue-skinned woman. A text bar on the cover promises readers an introduction to Paris's best cocktail bars and baignoires celebres, ‘famous bath-houses’, ramps-up the sexual explicitness. It would be unimaginable on an American news-stand.

-------

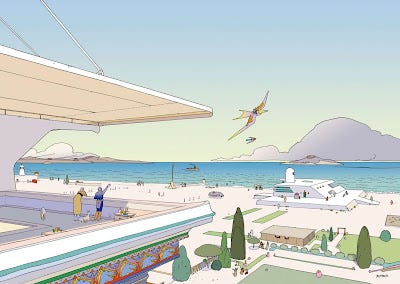

The most famous artist associated with Métal Hurlant is one of the magazine's founders: Jean Giraud, or ‘Mœbius’ (1938-2012). Giraud's first commissions were not for science-fiction projects, but illustrations for Westerns comics: starting with The Adventures of Lieutenant Blueberry. These bandes dessinées followed the peregrinations of a Civil-War-era anti-hero. Giraud had grown up obsessed with Western movies, and in 1956 he abandoned art school in France to Travel to Mexico, where is his mother had re-married a Mexican national. The nine months that he stayed there had a profound effect upon Giraud's artistic sensibilities: the wide, spacious landscapes under endless blue skies reinforced what he had so loved about Westerns in cinema. As a visual experience it was, he later said, ‘quelque chose qui m'a littéralement craqué l'âme’, ‘something which literally cracked open my soul’. After the Blueberry work he moved towards science-fiction and fantasy, blending illustrative ligne claire precision with gorgeously spacious, open-ended watercolour elaboration that re-rendered his imaginary Mexico into science-fiction. In addition to a great deal of Métal Hurlant work, Giraud worked for Marvel, designed for cinema and produced a variety of cover-art work.

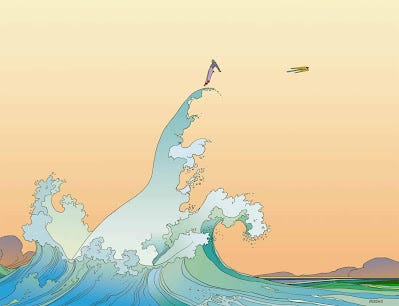

These are works of marvellous amplitude, capacious rendered spatialities that broach the sublime of science-fictional wonder in part by virtue of their combination of draughtsman-line precision and open-space pastel coloration. Mostly Giraud works in his own world: wide landscapes, figures in future-coded clothes, a sense of floating or gliding over amazing, alien worlds. When he engages famous prior art, as here with Hokusai's famous coloured woodblock Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831), he opens the image, widens it, and gives it an otherworldly splashiness of particular vigour:

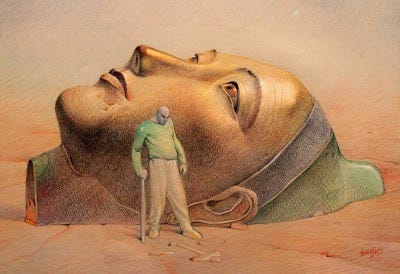

Given Giraud's topographic fascinations, it's not surprising that he was drawn to Shelley's sonnet Ozymandias:

Though his giganticism and scale-contrasts are more often than not sexualised.

... which brings us back to where we started.

Thanks for the introduction to Jean Giraud/Moebius.