I bought this Simenon—from a Bracknell charity shop, for 25p—with the intention of posting this joke on Bluesky. But having bought it, and done so, I read it. It is, of course, really good. One of the notable things about Simenon, as John Lanchester notes, is not just that he was astonishingly prolific (nobody is sure of the precise number of novels he wrote, but it is in the 400s, including 75 Maigret novels) but how consistent he is:

They are uncannily consistent in quality. Most prolific writers have oeuvres that look like mountain ranges: peaks and valleys. The masterpieces stand out as sunlit peaks, and shadowed abysses conceal the duds, where even the fans cough politely and move on to the next one. The Maigret books aren’t like that. When I tell people I’m a fan, I’m often asked which I think is best; although it’s a good and simple question, it stumps me. They are eerily alike in quality – no especial highs, no especial lows. How did Simenon achieve that? I suspect it’s because the process of writing Maigret involved Simenon going somewhere in his head, the place where Maigret lived. While Simenon was writing the books, he was in a room alone with his character; when he finished the book he stepped out of the room; when he had another idea he went back into the room, and there his reliable inspector was, waiting to go. The books are consistent because they all come from the same place.

All of which would be of little interest if the books were no good. Barbara Cartland wrote – or ‘wrote’, since she mainly dictated – up to 8000 words a day, and frequently finished two books a month; in 1976 she published 23 books; she wrote 723 books in total. Nobody cares, because they’re all shit. Simenon’s extraordinary fluency, and his equally extraordinary writing method, is only worth paying attention to because his books are so exceptional.

I’ve read a dozen or so Maigret and have yet to find a dud.

In Maigret Takes a Room (1951) Maigret’s wife is away in Alsace, looking after her sick sister; so the detective inspector is on his own. Two youngsters rob a nightclub at gunpoint, taking its cash-box, but both are ID’d. One, a Belgian, has taken his half of the money and gone to Brussels. The other, a French lad called Paulus, is staying in a guest house on the Rue Lhomond. The police go round to arrest him, but he’s not there—his half of the money is in his room, along with a toy pistol, the ‘gun’ used in the robbery. To catch him on his return, Maigret stations a policeman, Inspector Janvier, to watch the lodging house. But then Janvier is shot in the chest, one dark night. Rushed to hospital, the bullet is extracted, and it looks like Janvier will recover. But who shot him? And why?

Since he has no wife at home, Maigret decides to take a room in the lodging house and observe its inhabitants, scope-out the locale. That’s the story: Maigret getting to know the various people, and trying to puzzle-out why his inspector was shot. The owner of the house, Mademoiselle Clément—rotund, though, Simenon is at pains to stress, not unattractive—takes a fancy to him, and though nothing comes of it there is a frisson between them, a quasi-erotic connection. It turns out that handsome young Paulus is hiding out, literally underneath Mademoiselle Clément’s bed, although it seems she has not taken him as a lover (asked this specific question, Paulus replies, astonished, ‘she’s over forty!’), but is only hiding him out of a sense of kindness. Maigret checks-in on one of his inspectors, Vacher, one morning. Has he been OK? ‘The fat lady’s left me everything I need,’ Vacher tells him. ‘She got up a while ago to make me some coffee. She was in her nightdress. If I hadn’t been on duty, I’d willingly have made a move in that direction’ [118]. Though in her forties Clément has a youthful manner and ingenuous friendliness that registers as erotic. Across the road is the house in which lives Madame Françoise Boursicault. Where Clément is plump, jolly, active and optimistic, Boursicault is thin, withered, confined to her bed with some debilitating chronic illness, doleful and suspicious. She is married to a merchant seaman who is away much of the year. Maigret spends a lot of time in the novel observing the various inhabitants of Mlle Clément’s tenants, wondering if any of them are the shooter—having discovered the ingenuous young Paulus hiding under Clément’s bed he is soon able to eliminate him as a suspect.

The [spoiler] twist in the story is that the actual shooter has nothing to do with Clément’s lodging-house. Whilst her husband is away at sea, the bedridden Boursicault has been seeing her lover: an old flame, from before her marriage, and before her illness, when she was working as a waitress in a night-club. As a young man, in love with Françoise, this man had planned on marrying her; but then he got into trouble with a money-lender, whom he killed with a candle-stick. He then fled France and lived for eighteen years in Panama. Eventually coming back to France, he renews his relationship with the now-married Françoise, whilst her husband is at sea. But he is anxious not to be arrested for his previous crime, and doesn’t want to jeopardise his lover’s marriage. Trapped in the house, because of Janvier’s posting outside, knowing that Monsieur Boursicault is on his way home, he shoots the policeman and slips away. But although he planned to leave the country again, he couldn’t tear himself away from Françoise. The story ends with him in custody: Maigret is able to persuade him to turn himself in, on the understanding that if he doesn’t his lover Françoise will be arrested as an accomplice.

Simenon is excellent on vivid details, on noticing things. When Maigret visits Janvier in hospital, we’re told ‘it was the first time Maigret had seen the detective in bed.’ Description is sparse, and to the point: effectively so, although there are moments of unexpected vividness and descriptive lushness. ‘A broad beam of sunlight crossed the room, vibrant with fine particles of dust, as if the air had suddenly disclosed its intimate life.’ (The original French for this is even more euphoniously put: ‘un large faisceau de lumière traversait la chambre, tout vibrant d’une fine poussière, comme si soudain on découvrait la vie intime de l’air.’) What would, in another more overwritten book, strain or seem pretentious here works because the majority of the writing is so plain and unassuming. Here Maigret, new in the lodgings, leans out of his window.

L’air était d’une douceur de velours, presque palpable. Aucun mouvement, aucun bruit ne troublait la paix de la rue Lhomond qui descend en pente imperceptible vers les lumières de la rue Mouf fêtard. Quelque part, derrière les maisons, on percevait une rumeur, les bruits amortis d’autos qui passaient boulevard Saint-Michel, de freins, de klaxons, mais c’était dans un autre monde et, entre les toits des maisons, entre les cheminées, on jouissait d’une échappée sur un infini peuplé d’étoiles.

The air was soft like velvet, almost palpable. Not a movement, not a sound disturbed the peace of the Rue Lhomond which slopes gently down towards the lights of the Rue Mouffetard. Somewhere, behind the houses, could be heard a dull roar, the deadened noise of cars driving along the Boulevard Saint-Michel, of brakes and horns, but that was in another world and, between the roofs of the houses, between the chimneys, one could enjoy a glimpse of infinity inhabited only by stars.

Bold of Simenon to layer his cityscape this way, and to end on stellar infinities. It works because the rest of the prose, more or less, is plain, unadorned, unpretentious: it tells you a few facts, and much of the book is the to-and-fro of conversation, much of it Maigret questioning witnesses. As Maigret closes in on the killer, he waits, in his room, during a hailstorm.

A few moments later he was leaning on the window-sill; the window was open and it had stopped hailing. … the sky was brighter, but the sun had not yet come out, the light had the hardness of certain electric-light bulbs with frosted glass. There were hailstones scattered all along the pavement. [141]

Lovely writing, really. The killer walks into this scene, observed by Maigret from his window.

It’s striking how much Maigret drinks. At the beginning of the novel, returning from the hospital where his inspector is recovering from surgery, he telephones his wife; but before he does so he drinks a glass of sloe-gin [29]. That’s fair enough, perhaps: he’s just seen his friend and colleague at death’s door. The next day he has a meeting with his subordinates ‘at the bar counter, sinking white wine’ [25]. On the night he moves into the boarding house, to commence surveillance from within, the landlady supplies him with great draughts of crème de menthe: ‘she fetched the bottle of syrupy green liquid from the sideboard … he had not the strength of mind to refuse. The evening had consequently been one of green and blue, the green of the liqueur and the pale blue of the knitting which was lengthening imperceptibly in the landlady’s lap’. The following morning, significantly hung-over, he breakfasts: ‘he did not want any coffee, but a glass of white wine’ [52]. Breakfast of champions! Still, just one glass, right? Wrong! ‘Maigret drank three glasses of the white wine, which had greenish reflections in it’ [53]. Ouf! On his way back to the boarding house he stops in a bar ‘to make a telephone call’ and has a fourth glass [56]. A few nights later Maigret is readying himself for bed: ‘he went across to the bistro opposite, where he drank three glasses of beer, one after the other’, following this with ‘a glass of white wine’ [79]. The landlady, taking the measure of the man, ensures ‘there was always a bottle of beer on the table’ in his room, every evening. As he cudgels his brains to try and discover the assassin, Maigret ‘draws up a kind of time-table’ of the events of the evening, and ponders it: ‘or else he would go and drink a glass of white wine at the Auvergnat’s bar’ [85]. Zeroing-in on the actual criminal, he must interrogate Françoise Boursicault in the house opposite. So over he goes: ‘the inspector crossed the road once more, went first of all to have a glass of white wine, before going into the house’ [89]. Maigret’s net tightens on his suspect, but first ‘he went to the Auvergnat’s, intending to eat, but instead stopped at the bar and drank two glasses of wine, one after the other’ [112]. The following day? ‘He was drinking a glass of white wine, the first of the day, at the Auvergnat’s when the concierge returned from her shopping’ [131]. His last day in the boarding house, the landlady comes to say goodbye, in his room. ‘He opened the beer, which he drank from the bottle, because he had forgotten to bring up a glass, and the tooth-mug was of a not very appetising colour’ [142]. In British fiction it’s: ‘would you like a drink inspector?’ ‘Not while I’m on duty, ma’am, thank you’. In France it’s basically Chumbawumba’s ‘Tubthumping’: he drinks a whisky drink, he drinks a vodka drink, he drinks a lager drink, he drinks a cider drink.

More seriously, I was interested that this novel, set in a carefully observed and realised Paris of 1951, makes no mention whatsoever of the war. A mere six years previously, the largest armies the world has ever seen were fighting the most destructive war ever waged through northern France. Now there’s only one glancing, oblique reference to the fact: slowly, observant Maigret comes to have a sense of the little neighbourhood in which he has situated himself. ‘In a block of six houses, he had already come across five widows. He saw them go out each morning, carrying their shopping-baskets on their arms, to the market in the Rue Mouffetard’ [83]. We understand why 1951 Paris was so well-supplied with widows, though Simenon doesn’t spell it out, and makes no reference to the immediate history of the city.

What did Maigret do in Nazi-occupied Paris, 1940-44, we wonder?

There are no specific references to WW2 in any of the seventy five Maigret novels, from the first Pietr-le-Letton (1931) to the last Maigret et Monsieur Charles (1972), but the closely observed contemporaneity of each of them means they cannot but trace a France, and particularly a Paris, that evolves from the 1930s into the post-war period. (Two of Simenon’s non-Maigret’s romans durs are set in a specifically WW2 France: Le Train [1958] and Le Clan des Ostendais [1947]). This means that we get an in-effect social-history of France across the 20th-century, its day-to-day, its people and their work and pleasure, their passions and hatreds, but with this notable gap in the middle of it.

Maigret is based, critics agree, a little on Simenon himself and a little on his friend, the notable police inspector Marcel Guillaume. Simenon spent the war in the Vendée; in 1945 he was briefly arrested and investigated for collaboration, but he was acquitted: the worst of his activities seemed to have been selling the rights to a bunch of his novels to a Nazi film company. He left for America, but this was a move he had been planning for a while, not because he was fleeing France in shame about his behaviour in the war years. Guillaume retired as a policeman in 1937, before the Germans occupied Paris, and so was also a civilian during the war. Interestingly he was recruited back into the police in 1945 in order to be part of a team that investigated Adolf Hitler’s death.

And Maigret? In Maigret (1934) he has retired from the police, but in La Maison du Juge (1940) he is a working policeman, and no mention is made of him ever having left the job (although, for unclear reasons, in this story he has been posted away from Paris: to Normandy). Then in Cécile est morte (1942), Signé Picpus (1944), Félicie est là (1944) and L'Inspecteur Cadavre (1944) he’s again a policeman in Paris. It seems as if Maigret steps down from his job in 1945, since 1947’s Maigret se fâche is set two years into his retirement—although, of course, in dozens of postwar Maigret novels he’s back at the Sûreté, and Maigret se fâche doesn’t specifically date its events, or peg them to the war years. This is tricky though: in Maigret et son mort (1948) M. is on the force. In Les Mémoires de Maigret (1950) he has retired and is writing his memoirs, but in Maigret au ‘Picratt's’ (also 1950) he’s a working policeman again, as he is in all subsequent Maigret novels up until the last, Maigret et Monsieur Charles (1972), in which we are told Maigret’s retirement is imminent. It doesn’t overstretch things to suggest that 1940-44 marks a kind of aporia in Maigret’s career: he both is and is not a working policeman in Nazi-occupied Paris. As a French policeman he would inevitably have been involved in enforcing Nazi law, including the Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup of July 16–17 1942, in which Paris police, on the orders of the German occupiers, rounded up 13,152 Jews, including 4,115 children, and sent them to Auschwitz. Pretty much the entire Parisian police force, some 9000 men, took part in this operation. That’s not a comfortable thought. There’s some anti-Semitism in Simenon’s fiction from the 1930s through to the 1960s, though it is not a specific or pointed part of his writing. Maigret: collaborator.

Maigret en Meublé straddles the war: the present-day, 1951 crime, the shooting of Janvier, is revealed to be connected with a murder from eighteen years earlier, 1933. The murderer then, and shooter of Janvier now, is never named in the novel, which is an interesting textual strategy (‘But you don’t know my name’, he tells Maigret, and the policeman replies: ‘I shall know it sooner or later’ [138]). The nameless man who kills in France, flees across the Atlantic, and returns after the war.

This is to say, something is missing from the world of Maigret Takes a Room. It is a novel built around a palpable absence. On one side of the war ‘moneylender’, called Mabille, is murdered (could Simenon have been tipping the nod to Hélène Mabille, a famous Parisian heroine of the resistance, Jewish by birth—though ‘Mabille’ is not a Jewish name—who was arrested and sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp during the war, which experience she survived, just—she weighed 34kg when the Americans liberated her). On the other side of WW2, a policeman is shot in the chest and nearly dies. A nameless man, unmemorable-looking, ‘small and thin, dressed in grey, even his face had a greyish look; he might be either old and well-preserved or a young man prematurely aged’ [141], neither one thing nor another, is the centre of the crime. The mystery is, in essence, a cherchez la femme story, but the femme turns out to be not the voluptuous Clément, nor her lodger, the pretty 22-year-old would-be actress Blanche Dubut, who is supported by a mysterious ‘uncle’ whom Simenon never meets, and who enjoys the effect her allure has on men (when Maigret interrogates her she is wearing only a peignoir with nothing beneath, and Simenon notes ‘she thought, actually, that he was not displeased to see her in her dishabille’). But no, the femme is revealed to be a woman notable by her lack of conventional sex-appeal. When asked if she is attractive, Maigret rather brutally says ‘no, She’s almost fifty and she’s been bed-ridden for five years’. And yet she is the hinge around which the crime of passion turns.

This sense of absence is the ostensible premise of the novel—I mean, the actual absence of Madame Maigret. In almost all the Maigret novels she is there, to quote John Lanchester again: ‘the bourgeois home life and marriage of his main character are central to the books’ appeal. Madame Maigret is the source of that: she grounds the novels in diurnal reality. The novels are intensely domestic, balancing the psychological grimness of Maigret’s investigations, and the jet-black view of humanity embodied in his discoveries, with the comfort and routine of settled domesticity.’ Maigret en Meublé is the exception (in fact there are various others, but this is the one novel that opens on Maigret’s wife’s absence and Maigret’s discombobulation because of that). But this is a manifest absence, on the level of plot and storytelling; there is a latent, more significant absence—the war, the recent past of Paris, the Holocaust—which is what the book is more fundamentally about.

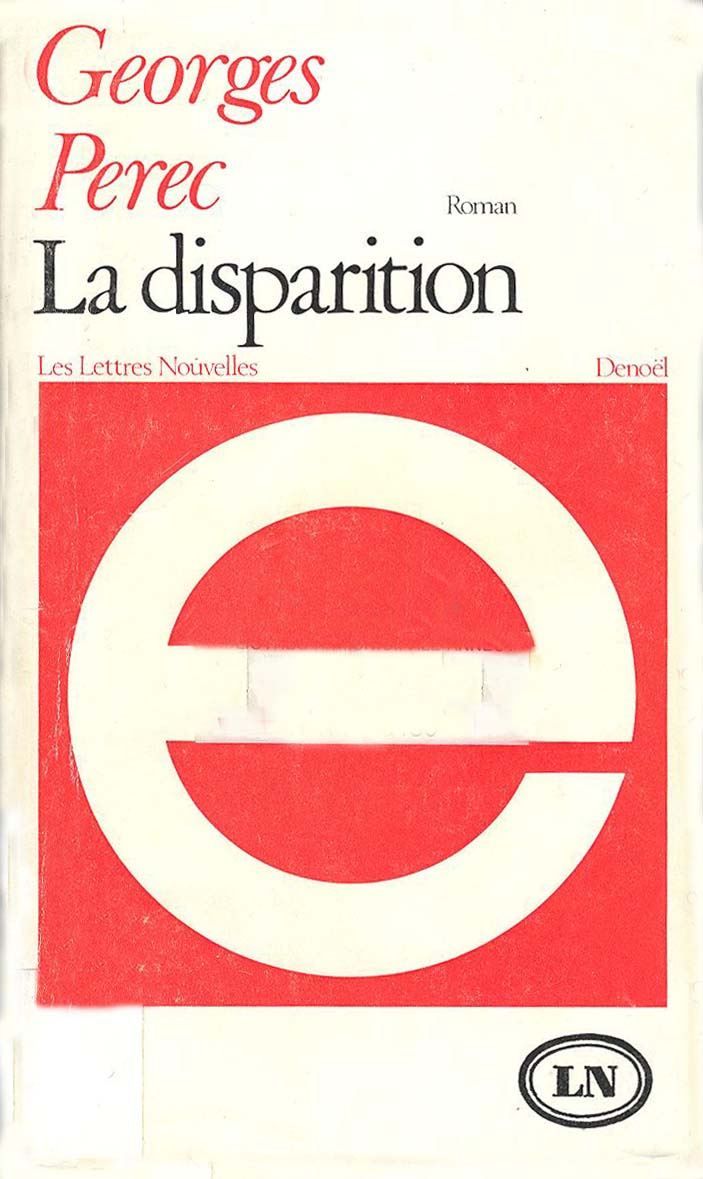

French Jew Georges Perec, whose father died as a soldier in the war in 1940 and whose mother died at Auschwitz, wrote La disparition (1969) as a Oulipo experiment: a novel written with normal sentence structure and correct grammar in which the letter e never appears—Perec deployed only words that do not contain the letter ‘e’ (it was ingeniously if a little stiffly and not over-accurately translated into English by Gilbert Adair under the title A Void, 1994). The main character in La disparition is Anton Vowl, a man frustrated the seemingly patternlessness of life, eager to discover the missing ‘signal’ that would make sense of everything, that would ‘knot-up this chain of discontinuous links.’ He keeps a diary recording his search, and expressing his frustration, but six months after beginning it he disappears. Is he dead? Friends try to solve the mystery, of A Vowl’s disappearance but also his awareness that ‘something else’ is missing, something that by virtue of its absence cannot be named. As the investigation goes on, one character after another is removed from the story, usually by violent death. After Cyrla Perec was deported from France to Auschwitz, all records of her cease; the only document Georges received regarding his mother’s fate was an Acte de disparition, ‘a certification of Disappearance’. That’s what haunts his 1969 novel, unnamed yet omnipresent. ‘For Perec, every detail of life gravitated toward that powerful void at the center, which the philosopher Maurice Blanchot, himself engaged with the question of how to approach the memory of the Holocaust (and also from the position of an indirect witness), described in terms of “time’s absence”’ [Eric Beck Rubin, ‘Georges Perec, Lost and Found in the Void: The Memoirs of an Indirect Witness’ Journal of Modern Literature, 37:3 (2014), 120]. The elimination of ‘e’ from the text is not just a textual whim: in French the letter e is pronounced like ‘eux’—them.

Simenon is writing a plain, expert policier, not an elaborate OULIPO experimental text; yet Maigret en Meublé is also about this unspeakable void, this absence at the heart of things. Madame Maigret has disappeared, gone East to Alsace—this debateable territory that is French but has been German—and Maigret has moved out of his solid home into the debateable environment of Mademoiselle Clément’s boarding-house. The original title of the novel means ‘Maigret in a furnished [room]’, but meubler can also mean ‘break the silence’. Hard to think of a way of Englishing the double-meaning, which is why the bland Maigret Takes A Room is used in UK editions. But this is a novel about the silence, the absence, the missing—the void—as much as the plot-line about a Parisian policeman taking a room in a lodging house.

Enjoyed the piece. I wonder if 'Maigret rooms alone' gets a bit closer to the feeling of the French. The silence of having no one to talk to, you've stepped out of the conviviality of 'normal' life