Goblins!

In George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin (1872), the beautiful princess Irene lives in a fantasy kingdom, fair and courteous in the sunlight, but whose hollow mountains and hills are infested with goblins that emerge at night. The goblins are plotting to kidnap the girl and forcibly marry her to the hideous Goblin prince Harelip, so Irene can only leave the safety of her castle by day. One night she strays and the goblins come after her, but she is rescued by a handsome young miner, called Curdie. Working underground, Curdie eavesdrops on a goblin scheme to flood the (human) mine workings with water. Eager to learn more, Curdie explores the labyrinthine goblin tunnels, using a Thesean ball of wool to trace his path, ‘for although he was not afraid of the cobs [goblins], he was afraid of not finding his way out.’ But then he is set upon:

Turning a sharp corner, he thought he heard strange sounds. These grew, as he went on, to a scuffling and growling and squeaking; and the noise increased, until, turning a second sharp corner, he found himself in the midst of it, and the same moment tumbled over a wallowing mass, which he knew must be a knot of the cobs. Before he could recover his feet, he had caught some great scratches on his face and several severe bites on his legs and arms. But as he scrambled to get up, his hand fell upon his pickaxe, and before the horrid beasts could do him any serious harm, he was laying about with it right and left in the dark. The hideous cries which followed gave him the satisfaction of knowing that he had punished some of them pretty smartly for their rudeness, and by their scampering and their retreating howls, he perceived that he had routed them. He stood for a little, weighing his battle-axe in his hand as if it had been the most precious lump of metal — but indeed no lump of gold itself could have been so precious at the time as that common tool. [The Princess and the Goblin, ch 18]

In H G Wells’s The Time Machine (1895), a nineteenth-century man uses his titular machine to travel to the far future, where he discovers child-like descendants of humanity frolicking in the sunshine , amongst them a beautiful child-girl called Weena. But the land is plagued by goblin-like Morlocks, cunning and malicious beings who dwell inside the hollow earth and come out at night. These beings have designs upon Weena, and the Time Traveller must fight them off:

Morlocks were closing in upon me. Indeed, in another minute I felt a tug at my coat, then something at my arm. And Weena shivered violently, and became quite still … I lit a match, and as I did so, two white forms that had been approaching Weena dashed hastily away. One was so blinded by the light that he came straight for me, and I felt his bones grind under the blow of my fist. He gave a whoop of dismay, staggered a little way, and fell down … I was caught by the neck, by the hair, by the arms, and pulled down. It was indescribably horrible in the darkness to feel all these soft creatures heaped upon me. I felt as if I was in a monstrous spider’s web. I was overpowered, and went down. I felt little teeth nipping at my neck. I rolled over, and as I did so my hand came against my iron lever. It gave me strength. I struggled up, shaking the human rats from me, and, holding the bar short, I thrust where I judged their faces might be. I could feel the succulent giving of flesh and bone under my blows, and for a moment I was free. The strange exultation that so often seems to accompany hard fighting came upon me. I knew that both I and Weena were lost, but I determined to make the Morlocks pay for their meat. I stood with my back to a tree, swinging the iron bar before me. [The Time Machine, ch 12]

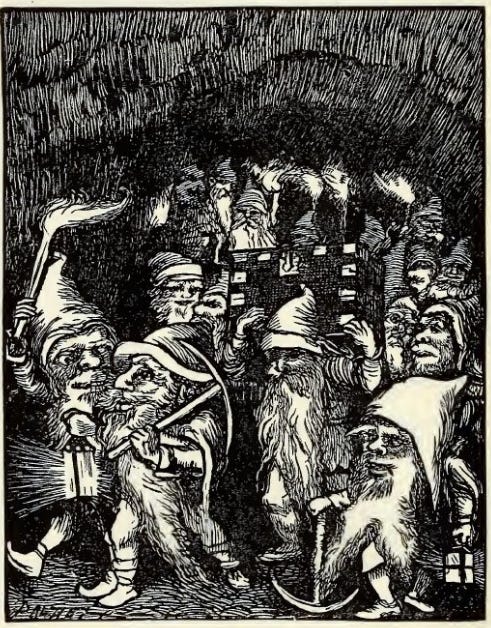

In J R R Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937), some travellers are making their way through the mountains when, out of the hollow depths of the world, goblins ambush them.

Out jumped the goblins, big goblins, great ugly-looking goblins, lots of goblins, before you could say rocks and blocks. There were six to each dwarf, at least, and two even for Bilbo; and they were all grabbed and carried through the crack, before you could say tinder and flint. But not Gandalf. Bilbo’s yell had done that much good. It had wakened him up wide in a splintered second, and when goblins came to grab him, there was a terrific flash like lightning in the cave, a smell like gunpowder, and several of them fell dead … Just at that moment all the lights in the cavern went out, and the great fire went off poof! into a tower of blue glowing smoke … The yells and yammering, croaking, jibbering and jabbering; howls, growls and curses; shrieking and skriking, that followed were beyond description. Soon they were falling over one another and rolling in heaps on the floor, biting and kicking and fighting as if they had all gone mad. Suddenly a sword flashed in its own light. Bilbo saw it go right through the Great Goblin as he stood dumbfounded in the middle of his rage. He fell dead, and the goblins soldiers fled shrieking into the darkness. [The Hobbit, ch 4]

A rite of passage, then, for the Hero on his quest: to get to the treasure, to win the girl, you must first fight off the swarming goblins with a spar of metal in your hand! Except that Time Traveller loses the girl, and Gandalf isn’t exactly the hero (and Bilbo marries no princess at the end of his adventures). Still: one fights off goblins with the tool that one has to hand: pickaxe, metal spar, sword.

Dictionaries still suggest that the word goblin, and its synonym kobold, derive from the Greek word, κόβᾱλος (kóbālos): ‘impudent rogue, arrogant knave’, and ‘(in the plural) mischievous goblins invoked by rogues’. But ‘Gideon’, in this fascinating post on the linguistic history of κόβᾱλος, demonstrates not only that the Ancient Greeks did not use the word to refer to goblin-style creatures, but that it came into English after the word goblin. Wiktionary has an alternate etymology for the German Kobold, which may be more relevant: ‘Kobe + holt’ a shed or sty ‘friendly one’, this last a euphemistic way of referring to dangerous supernatural entities: as with the Greek Eumenides. As to where κόβᾱλος came from, it might be related to κάβαξ (kábax, “crafty, knavish”) — or it might have something to do with κοβαλεύω ‘to carry as a porter’. Are goblins the embodiment of malevolent mischief?— something of which the world around us only too often seems to manifest, and which cries out to be anthropomorphised (like gremlins on an airplane) in our storytelling? Or are goblins, actually, our servants: bent double under the loads we make them carry, liable to rise-up and attack us if we don’t keep them down by beating them with a pickaxe, metal spar or sword?

Tolkien was always up-front that the goblins of The Hobbit owe a great deal to George MacDonald’s work: he wrote to Naomi Mitchison ‘Goblins … are not based on direct experience of mine but owe, I suppose, a good deal to the goblin tradition, especially as it appears in George MacDonald, except for the soft feet which I never believed in. [Letters, 144]. Adaptations of Tolkien into other media have differentiated goblins and orcs as different types of creature, but for Tolkien himself ‘orc’ and ‘goblin’ are synonyms. As the preface to The Hobbit says: ‘Orc is not an English word. It occurs in one or two places but is usually translated goblin (or hobgoblin for the larger kinds)’. That said, writing The Lord of the Rings Tolkien moved to distance his goblins from the goblin tradition, referreing to them as orcs. Mitchison disagreed, and he wrote to her: ‘your preference of goblins to orcs involves a large question and a matter of taste, and perhaps historical pedantry on my part. Personally I prefer Orcs (since these creatures are not “goblins”, not even the goblins of George MacDonald, which they do to some extent resemble’) [Letters 151]

[dips toe in etymology of 'goblin']

[shakes head sadly over OED entry]

[dips toe a bit further]

[pulls foot out before it gets bitten off]

The OED entry really does look a bit of a mess - it doesn't look like there ever was a med. L. 'cobalus' - but beyond that I'm not going. There also seems to be general agreement that the original goblins/kobolds were brownie-like protective and helpful house spirits, but that the ones you met down the mine were mischievous at best. Why this was, who knows?

Victorian goblins are something else again, and will have been absolutely loaded with repressed middle-class guilt and eugenic fantasy. H.G. Wells, being a progressive and rational person, won't have had any truck with that sort of nonsense, though.

Yes, thanks! (I suspect you and I are among the very few who've written studies of orcs/goblins and of Fredric Jameson! ;) )