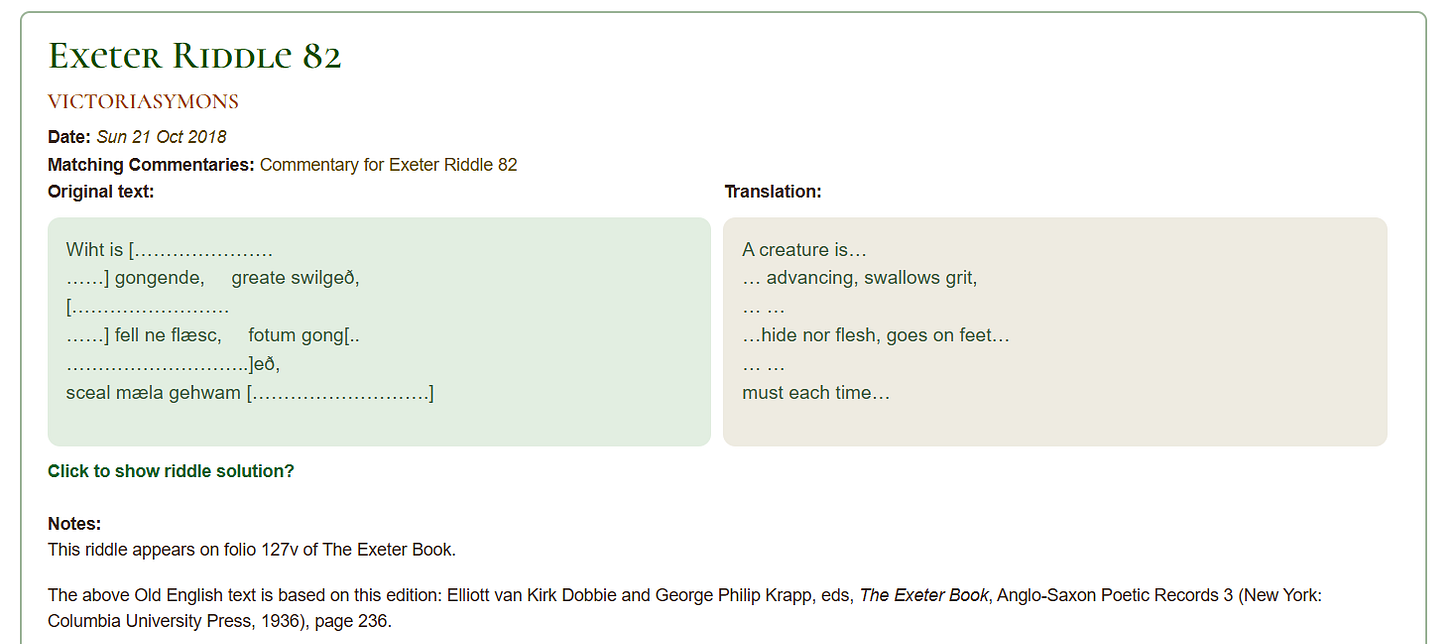

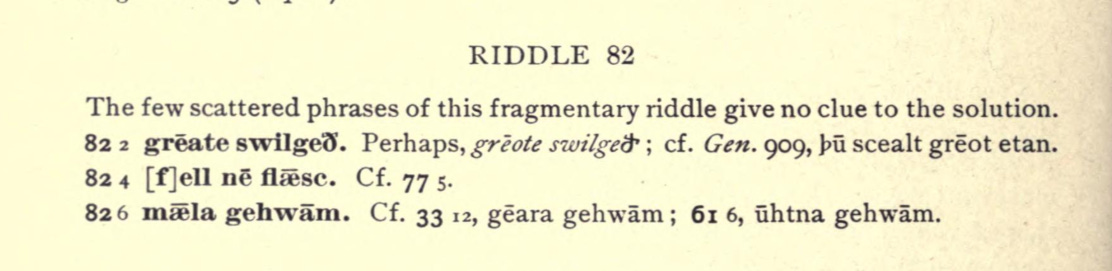

Some of the riddles in the celebrated Exeter Book are complete, and we know their solutions; some are complete and scholars argue over possible answers to them. But Riddle 82 is tantalisingly fragmentary, such that nobody is entirely sure what it’s saying, let along what its answer might be. Above is a screenshot from the excellent ‘The Riddle Ages’ website, where UCL’s Dr Victoria Symons offers her translation of the riddle’s four (of six) incomplete lines, and suggests possible answers. Suggesting possible answers is further than Frederick Tupper’s venerable The Riddles of the Exeter Book (Boston 1910) is prepared to go:

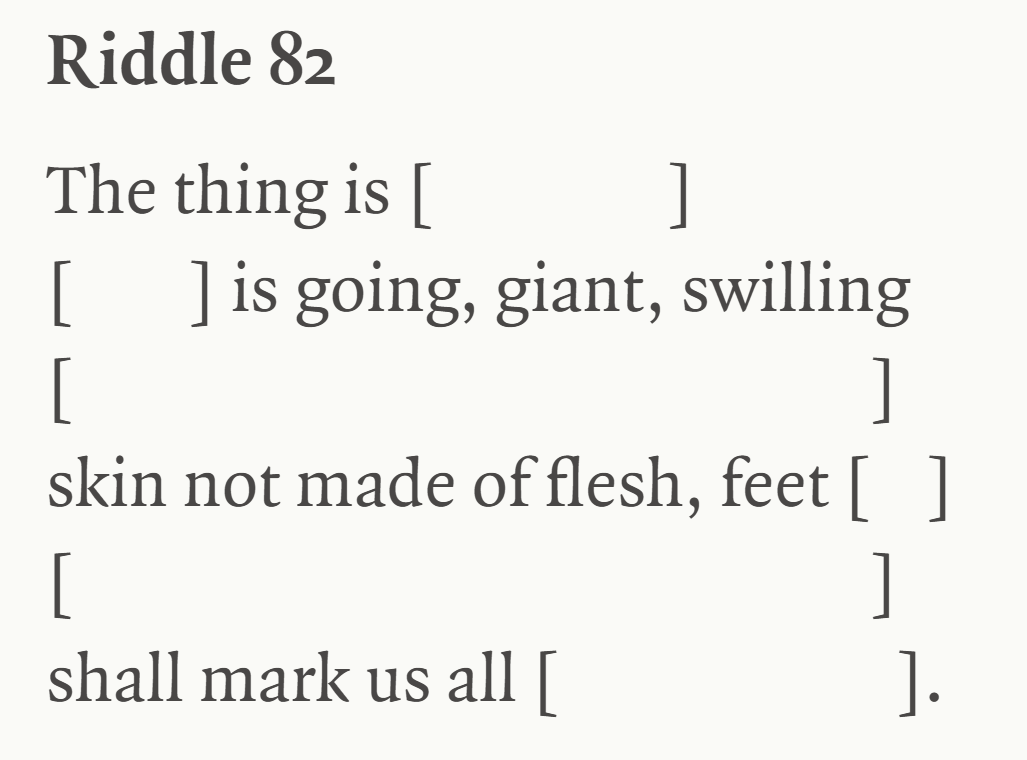

And here is American poet Miller Wolf Oberman’s version:

This plays games with the riddle which, since riddling is inherently ludic, might be thought only fitting. The actual text starts Wiht is, where the first word means both ‘creature, being’ (the later, but now archaic, ‘wight’ is a version of this word) and also more generally ‘thing’ (the term ‘whit’ descends from this, as in the phrase ‘to care a whit’). But ‘The thing is …’. especially with the (enforced) ellipsis that follows it, reads like a piece of phatic conversational filler (‘The thing is … my parents like me to be home by ten o’clock’; ‘The thing is … the shops close early on Sundays’) which cuts interestingly across the specificity a riddle complexly provides. Oberman manages accurately to translate the Old English whilst also creating un-Anglo-Saxon John Ashbery conversational casualness. In this context I like the implied hesitancy of ‘the thing is … is …’ and the groping for words of ‘going, giant, swilling’, arriving at the more certain assertion that this thing, whatever it is, shall mark us all. It’s a poem where ellipsis simultaneously records gaps in its source material and enacts a kind of hesitant caution or inarticulacy of expression, as if overwhelmed by what it is trying to say.

And what is the thing? The second line depends upon whether we read greate as ‘great, big, coarse, massive’ (which it could be) or as greot, ‘grit, earth, soil, sand’, as old Tupper suggests above, which: it also could be. My understanding is that scholars of the riddles nowadays believe this latter to be the meaning, although Oberman’s ‘giant’ goes with the former. The next words, …ell ne flæsc, assumed because of alliteration to be fell ne flæsc, could be ‘[neither] skin nor flesh’ or ‘skin [that is] not flesh’. And finally sceal mæla gehwam, depends upon how we take mæl, which can mean: ‘a measure’ ‘sign (especially a cross)’, ‘time, occasion, season’, ‘cares or troubles of the time’ or ‘a meal’. Victoria Symons takes it as ‘time’; Oberman as ‘mark’; I wonder if it could possibly be a version of *mehl, mala, malan, ‘grind’, which would go with the grit reference earlier (if indeed that is a reference to grit).

Oberman’s version has a Poundian vibe: like Pound’s deliberately fragmentary ‘Papyrus’, alluding to the incomplete fragments of Sappho.

Oberman’s isn’t confected, as Pound’s is, although by printing it as a standalone poem, as he does, he taps into the suggestivity of Pound’s poetic strategy. ‘Riddle 82’ becomes a poem about something rather ominous: something with skin—a point of contact with us—but no flesh behind it; something growing, swallowing things as it goes, an already gigantic entity that, like Revelation’s mark of the beast, shall mark us. To which, for a poem published in 2017, makes me think: the internet.

By contrast, Victoria Symons, translating ‘A creature is…/advancing, swallows grit,/ … hide nor flesh, goes on feet/… must each time…’ offers two possible solutions to the riddle, both in keeping with the Anglo-Saxon culture that produced the original text. Those two answers are: crab, or harrow. I can see how the former, but not the latter, goes on legs; and I can see how the latter, but not the former, swallows soil. Hard, too, to see how a crab has ‘neither hide nor flesh’: it has a shell rather than a ‘fell’, sure: but its flesh is famously delicious, as much a delicacy in Anglo Saxon times as today (though if fell ne flæsc means ‘skin that is not flesh’, then ‘crab’ would fit).

I have a different theory as to what this riddle is riddling: entirely speculative, of course, but that’s no reason not to post it.

Wiht is wandrian and æfre wundorlic Grene gongende, greate swilgeð, Bæc his bēag swā swiðe brād brycg Nawþer fell ne flæsc, fotum gongen, Hēah hægde tō help þæt fealleð Sceal mæla gehwam hēon weall reweorc.A wight is wandering, always wondrous, Green, going-onward, swallowing grit, Arching his back like a broad bridge Neither skin nor flesh, going on feet, A high palisade to protect, that falls And must each time rebuild its wall.

… to which the answer, of course, is: a wave breaking on the shore.

What if it's a book of poems? This would make 'feet' metrical, and 'hide' as in 'leather bound'.

Re: feet, a harrow has tines like a rake, doesn't it? But I like your reconstruction, particularly the sense it makes of the 'must each time' snippet (what do you call a fragment of a fragment?).