1

I’ve been re-reading Dickens’s Christmas books for the season.

So: after the huge success of A Christmas Carol (1843) Dickens produced, annually, four further ‘Christmas Books’, illustrated novellas on Christmas or New Year themes. But where the Carol endures, and is indeed by far the most famous and widely-loved thing Dickens produced, the other four titles haven’t: The Chimes (1844), The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), The Battle of Life (1846) and The Haunted Man (1848). It would be too harsh to say that they are rubbish, but: well—they pretty much are. Least likeable of all of them, perhaps, is The Chimes (1844), Dickens’s immediate follow-up to A Christmas Carol. What’s odd is that Dickens didn’t think so: he really rated this work, and indeed continued, through his life, to think it one of the best things he had written.

The idea for it came to him whilst he and his family were living in Italy in 1844, when (this is John Forster’s account in his Life of Dickens):

… all Genoa lay beneath him, and up from it, with some sudden set of the wind, came in one fell sound the clang and clash of all its steeples, pouring into his ears, again and again, in a tuneless, grating, discordant, jerking, hideous vibration that made his ideas ‘spin round and round till they lost themselves in a whirl of vexation and giddiness, and dropped down dead.’

He wrote the book quickly, writing to Forster that the new book was ‘as unlike [A Christmas Carol] as such a thing can be’; and, once he had completed the manuscript, he wrote to another friend Thomas Mitton, ‘I believe I have written a tremendous book, and knocked the “Carol” out of the field.’ How could he get this so wrong? Not just him, but his friends. On a flying visit to London to correct proofs, Dickens read the story aloud to a group of friends: Daniel Maclise reported ‘shrieks of laughter, floods of tears’ among this audience. Dickens wrote to his wife Catherine, still in Italy: ‘if you could have seen Macready last night—undisguisedly sobbing, and crying on the sofa, as I read—you would have known what it is to have Power.’ It’s not a power that has carried through into posterity, it must be said.

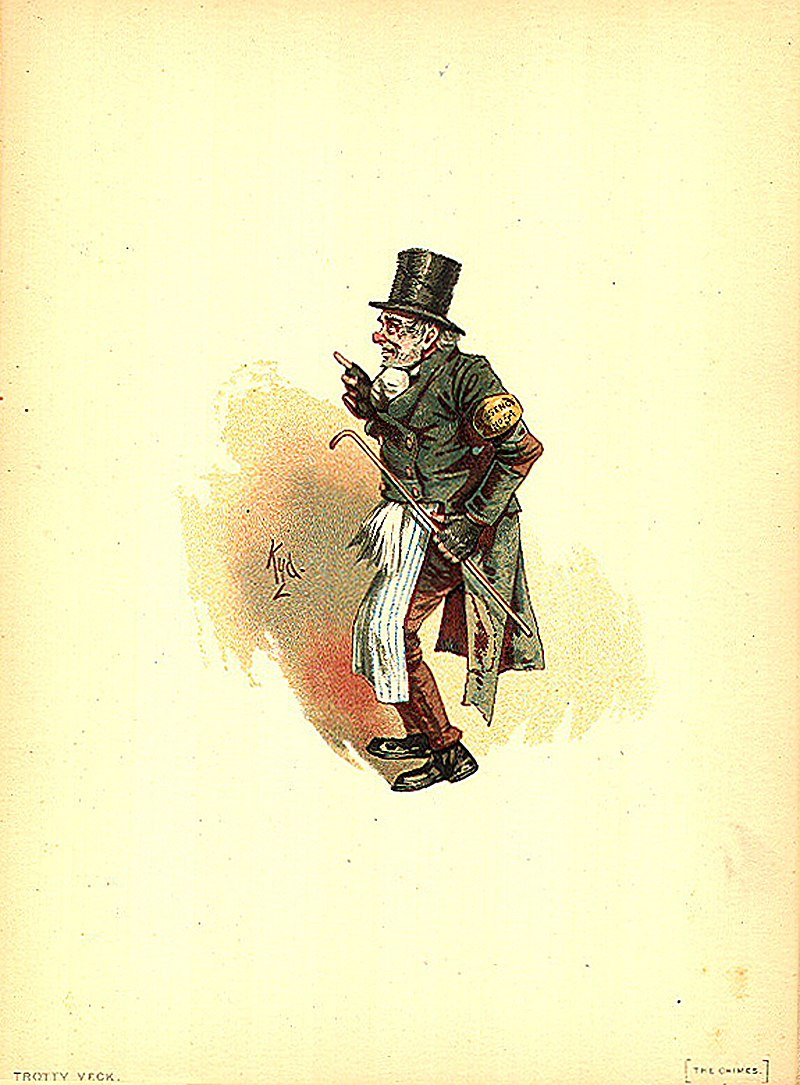

Toby Veck, the protagonist, is a poor elderly ticket-porter, known as ‘Trotty’ because of his gait as he scurries from place to place.

His job is carrying messages and letters within the city of London—the first penny black postage stamps had only just come in, in 1840, and the first red pillar box would not arrive until 1852: which is to say, within decade or so the Royal Mail would render ticket-porters redundant. In the later 19th century, London had between six and twelve posts a day, allowing correspondents to hold conversations by post: a worker in the city could write to let his wife know what time he would be home that day, and she could write a reply to tell him to pick up some groceries on the way. But that’s the future: it’s not clear to me if Dickens is positioning Trotty as someone about to be swept away by the new logic of the mail, or not. He is, certainly, a pathetic figure: old, broken down, poor and prone to despair and self-loathing. This latter is a main element in the story, in fact, and it makes the book hard to like—The Chimes, as Paul Schlicke argues, lacks the fundamental geniality of Carol, and Trotty’s sufferings, which are supposed to work reformation in him, involve putting a fundamentally decent, good-hearted individual through the wringer. It’s painful to read, the final redemptive happy-ending something of a non sequitur as well as being oddly ambiguous.

The book is in four chapters, each called a ‘quarter’, as per a chiming clock, though the titular chimes are not clock- but church-bells (the church in the story is not named, but Dickens based it on St Dunstan-in-the-West, on Fleet Street; its Victorian bells, destroyed in the war, were replaced in 1969, so its peels today are not what Dickens would have heard). The first two quarters of the book contain no supernatural or seasonal elements, and give the story a very slow start. Trotty trots about delivering messages. His grown-up daughter,; Meg, and her boyfriend Richard announce that they will marry. But this is the Hungry ’40s, and they are desperately poor. Alderman Cute (a figure based on Sir Peter Laurie) and Mr Fiker, a political economist and utilitarian (based, I think, on Mill) deprecate this marital ambition: the poor should not marry.

Ah!’ cried Filer, with a groan. ‘Married! Married!! The ignorance of the first principles of political economy on the part of these people; their improvidence; their wickedness; is, by Heavens! enough to—Now look at that couple, will you!’

Laurie assures Meg and Richard that their marriage will be a disaster: they will have children who will turn out bad; Richard will die young ‘most likely’, and leave Meg with a baby. She will be turned out to wander the streets: ‘don’t wander near me, my dear,’ he tells Meg, ‘for I am resolved to Put all wandering mothers Down.’ Trotty is persuaded, to his sorrow. Overhearing Cute say that he plans to arrest a certain poor countryman, Will Fern, for vagrancy, Trotty later chances upon Fern on the streets, with his nine-year-old orphaned niece, Lilian: he urges them to avoid Cute, and takes them to his own home, poor though it is, where he and Meg shares their meagre food with the pair. Meg, upset, appears to have given up the idea of marrying Richard.

Trotty takes to heart all the statements of Alderman Cute, Filer, and another character, the wealthy MP Sir Joseph Bowley, as to the improvidence and badness of the poor. That evening, in his home, matters come to a despairing head. One of the germs of The Chimes was the case of Mary Furley, a young Londoner. Unmarried, with a small child, and destitute on the streets of the city, Furley was so afraid of being sent to the workhouse that she jumped in the Thames to kill herself and her baby. In the event she was rescued but her child died. She was charged with its murder, and convicted. The case was widely discussed and debated. On the one hand was Peter Laurie, who argued that the only way to reduce suicides was to criminalise it, ensuring that any who survived would be strictly prosecuted, as a deterrent to others who might be considering killing themselves, and to indicate society’s disapproval. On the other hand was Dickens who, in an article in Hood’s Magazine (May 1844) argued that the case was tragic not criminal, and that Furley’s sentence was unjust. In The Chimes Dickens has Alderman Cute admonish Meg: ‘if you attempt, desperately, and ungratefully, and impiously, and fraudulently attempt, to drown yourself, or hang yourself, I’ll have no pity for you, for I have made up my mind to Put all suicide Down!’ (In the event, and following a public outcry, Furley’s capital sentence was commuted to transportation).

Later that night, Trotty is reading the newspaper at home.

He came to an account (and it was not the first he had ever read) of a woman who had laid her desperate hands not only on her own life but on that of her young child. A crime so terrible, and so revolting to his soul, dilated with the love of Meg, that he let the journal drop, and fell back in his chair, appalled!

‘Unnatural and cruel!’ Toby cried. ‘Unnatural and cruel! None but people who were bad at heart, born bad, who had no business on the earth, could do such deeds. It’s too true, all I’ve heard to-day; too just, too full of proof. We’re Bad!’

At this the bells suddenly start up, and Toby Veck believes them to be calling him. ‘Toby Veck, Toby Veck, waiting for you Toby! Toby Veck, Toby Veck, waiting for you Toby! Come and see us, come and see us, Drag him to us, drag him to us, Haunt and hunt him, haunt and hunt him, Break his slumbers, break his slumbers’

Trotty leaves his house, enters the empty midnight church and climbs the belltower: ‘Still up, up, up; and round and round; and up, up, up; higher, higher, higher up!’ When he reaches the top, he is overwhelmed by a ‘heavy sense of dread and loneliness’ and sinks into a swoon.

Now the supernatural part: the Third Quarter opens with Trotty waking from his swoon to see the bells all around him being rung by goblins:

The tower [was] swarming with dwarf phantoms, spirits, elfin creatures of the Bells. He saw them leaping, flying, dropping, pouring from the Bells without a pause. He saw them, round him on the ground; above him, in the air; clambering from him, by the ropes below; looking down upon him, from the massive iron-girded beams; peeping in upon him, through the chinks and loopholes in the walls; spreading away and away from him in enlarging circles, as the water ripples give way to a huge stone that suddenly comes plashing in among them. He saw them, of all aspects and all shapes. He saw them ugly, handsome, crippled, exquisitely formed. He saw them young, he saw them old, he saw them kind, he saw them cruel, he saw them merry, he saw them grim; he saw them dance, and heard them sing; he saw them tear their hair, and heard them howl. He saw the air thick with them. He saw them come and go, incessantly. He saw them riding downward, soaring upward, sailing off afar, perching near at hand, all restless and all violently active. Stone, and brick, and slate, and tile, became transparent to him as to them. He saw them in the houses, busy at the sleepers’ beds. He saw them soothing people in their dreams; he saw them beating them with knotted whips; he saw them yelling in their ears; he saw them playing softest music on their pillows; he saw them cheering some with the songs of birds and the perfume of flowers; he saw them flashing awful faces on the troubled rest of others, from enchanted mirrors which they carried in their hands.

[Daniel Maclise’s design for the frontispiece of The Chimes]. In Carol, the vividly individuated ‘three spirits’ personalise the supernatural redemptive experience through which Scrooge passes; this myriad—arriving belatedly in the story more than halfway through—do not. They are legion because Dickens wants to say something about society as a whole, not just one miserly misanthrope. But it dilutes the force of the supernatural intervention.

The ‘Goblin of the Great Bell’, the largest of this species, addresses Toby. He shows him Trotty’s dead body, lying on the ground at the bottom of the tower—he had fallen from its height to his death, and done so nine years before. Then the Great Bell shows Trotty what has happened to all the other characters in the story in that time, and it is nothing good: the pair Trotty brought home, Will and Lilian, have gone to the bad: the former in and out of prison, the latter becoming a prostitute. Meg, having initially refused to marry Richard, watched him descend into alcoholism; in an attempt to save him, Meg did marry him, but he drinks himself to death leaving her with a baby. Destitute and homeless, Meg decides to drown herself and her child, as Mary Furley, about whom Trotty read in his newspaper, had done before. Trotty, seeing this in visionary form, weeps: crying out that he has learned his lesson. He tries to restrain her from jumping in the river, but, being only a ghost, he has no material grip upon her. The goblin spirits stand in myriads above him. ‘O, save her, save her!’ he cries.

He could wind his fingers in her dress; could hold it! As the words escaped his lips, he felt his sense of touch return, and knew that he detained her.

The figures looked down steadfastly upon him.

‘I have learnt it!’ cried the old man. ‘O, have mercy on me in this hour, if, in my love for her, so young and good, I slandered Nature in the breasts of mothers rendered desperate! Pity my presumption, wickedness, and ignorance, and save her.’ He felt his hold relaxing. They were silent still.

‘Have mercy on her!’ he exclaimed, ‘as one in whom this dreadful crime has sprung from Love perverted; from the strongest, deepest Love we fallen creatures know! Think what her misery must have been, when such seed bears such fruit! Heaven meant her to be good. There is no loving mother on the earth who might not come to this, if such a life had gone before. O, have mercy on my child, who, even at this pass, means mercy to her own, and dies herself, and perils her immortal soul, to save it!’

She was in his arms. He held her now. His strength was like a giant’s.

At this climax, Trotty wakes. He is at home, Meg sitting happily in the corner sewing. It was all a dream. What remains is: Richard and Meg do marry, and the final scene of the novel is a jolly wedding celebration, Will and Lilian finding the friend for whom they were searching in London and avoiding vagrancy, and all living happily ever after. Then Dickens’s envoi:

Had Trotty dreamed? Or, are his joys and sorrows, and the actors in them, but a dream; himself a dream; the teller of this tale a dreamer, waking but now? If it be so, O listener, dear to him in all his visions, try to bear in mind the stern realities from which these shadows come; and in your sphere endeavour to correct, improve, and soften them. So may the New Year be a happy one to you, happy to many more whose happiness depends on you! So may each year be happier than the last, and not the meanest of our brethren or sisterhood debarred their rightful share, in what our Great Creator formed them to enjoy.

Trotty only dreamt his travails with the bell-goblins; or perhaps he didn’t dream it, and it was ‘real’, the dream being the author’s, Charles Dickens. Either way, we are exhorted, in a slightly inconsecutive way, to ‘correct, improve and soften’ the harsh realities of economic and social life. Does Trotty have a bright future? The inevitable coming of the Royal Mail and its stamps suggests not. Will Richard and Meg live happily ever after? That will depend on whether they have enough money, which is by no means assured, as the hungry 40s grind on.

So: Scrooge is a misanthrope and miser who despises and mistreats his fellow men and women, and that is why the spirits force him through all the events of a Christmas Carol, so that he can see the error of his ways and repent. But Trotty? He’s neither misanthrope nor miser (he doesn’t have any money with which to be miserly); on the contrary he’s a kind-hearted, generous and within the limit of his means charitable individual. No: Trotty is put through the ringer because he despaired, and fell into self-loathing, or more specifically a loathing of his whole class, the poor. The goblins show him a vision of the future (from his 1844 perspective) revealing what such despair entails: misery and death spreading out, like ripples from a stone plunged into a pond. But what saves Trotty is not an awakening to general benevolence, but the specific impulse to save his own daughter—like Darth Vader being ‘redeemed’, after killing and terrorising billions, because he baulks at seeing his own son killed in front of him: that’s hardly selflessness. Not that Toby Veck is a Sith: on the contrary, he is a decent, kindly, good-hearted old man. His wickedness is not exploding Alderaan, but giving way to despair—the same thing that put Mary Furley in the dock, that afflicts Meg, that is behind, we can intuit, Richard’s decline into alcoholism. But depression is not a moral failing, it is an illness, and it is not ‘cured’ by sudden manic bursts of enthusiasm. This recalls Edmund Wilson’s ‘The two Scrooges’, an essay that in effect diagnoses Scrooge with manic-depression and says (more or less): but we know how this pathology goes—from miser(able) withdrawal from humanity into gloom and solitude, through hyper-manic episodes of exaggerated sociability and generosity. But the manic-depressive doesn’t move from depression to mania and then settle into well-balanced psychological health. He doesn’t even move from depression to mania and then stay there. Whatever the last paragraph of Carol says, we understand what will happen to Scrooge: his episode of Christmas mania will give way to another long, desperate period of depression. Believe me, I know whereof I speak on this matter.

This is only to say that Scrooge, as characterm, ‘feels’ like a real person, and I’m not convinced that Toby Veck does. The goblins themselves seem egregious: there is an intuitive rightness to Marley’s ghost, and the three spirits, as vehicles for the story-arc of Carol that isn’t present with the goblins and the bells and all these women jumping into the Thames to drown themselves in despair. The goblins are set-dressing, a swarm of supernatural oddness, no sooner introduced than distilled down to one, the goblin of the Great Bell, who acts as an externalisation of conscience.

I’d go further, and suggest that the two main imaginative prompts under which Dickens wrote The Chimes are at odds: one, the cacophonous ringing of Genoese bells, two, poor Mary Furley and her attempted suicide and the death of her baby. But these two have no obvious associative or imaginative connection. More, I’d suggest that the moment in The Chimes that work are expressions of the latter, not the former, for all that it is the former that gives the book its title. So, the scene where the desperate ghostly father attempts to hold his suicidal daughter, to prevent her leap into the river, but cannot because he is only a spectre, until the sheer force of his remorse and love for his daughter starts to add materiality to his fingers, his hand, and, finally, is able to clasp her: ‘he held her now, his strength was like a giant’s.’ That’s genuinely affecting. But the flood, rather than the chime, is what speaks thematically. As Trotty wakes from his swoon at the beginning of the Third Quarter, Dickens gives us this:

Black are the brooding clouds and troubled the deep waters, when the Sea of Thought, first heaving from a calm, gives up its Dead. Monsters uncouth and wild, arise in premature, imperfect resurrection.

That’s a powerful image—the sea of thought giving up its dead, as the actual sea will do at the apocalypse: the monstrous forms that return, to slip into an anachronistic Freudianism for a moment, out of the Repressed, goblins and monsters. It resonates with the Thames flood that drowned Mary Furley’s baby and nearly killed her; and into which Meg gazes, with her baby. After he is able to hold his child and stop her killing herself, Trotty exclaims thuswise, addressing the world:

‘I see the Spirit of the Chimes among you! I know that our inheritance is held in store for us by Time. I know there is a sea of Time to rise one day, before which all who wrong us or oppress us will be swept away like leaves. I see it, on the flow! I know that we must trust and hope, and neither doubt ourselves, nor doubt the good in one another. I have learnt it from the creature dearest to my heart. I clasp her in my arms again. O Spirits, merciful and good, I take your lesson to my breast along with her! O Spirits, merciful and good, I am grateful!’

This, I think, is Dickens’s version of his friend Carlyle’s exhortation in Past and Present (Dickens was particularly solicitous that Carlyle be given a pre-publication copy of The Chimes) to justice:

Foolish men imagine that because judgment for an evil thing is delayed, there is no justice, but an accidental one, here below. Judgment for an evil thing is many times delayed some day or two, some century or two, but it is sure as life, it is sure as death! In the centre of the world-whirlwind, verily now as in the oldest days, dwells and speaks a God. The great soul of the world is just. O brother, can it be needful now, at this late epoch of experience, after eighteen centuries of Christian preaching for one thing, to remind thee of such a fact; which all manner of Mahometans, old Pagan Romans, Jews, Scythians and heathen Greeks, and indeed more or less all men that God made, have managed at one time to see into; nay which thou thyself, till 'redtape' strangled the inner life of thee, hadst once some inkling of: That there is justice here below; and even, at bottom, that there is nothing else but justice! Forget that, thou hast forgotten all. [Carlyle, Past and Present, 2]

As Michael Slater noted in 1970 that ‘The Chimes is indeed written so much in the spirit and occasionally even in the very idiom of Carlyle's social writings that it seems odd it is not noticed’.

But this imagery of floods and flooding, of the great uprising of water as the corelative of the plunge into drowning waters, has nothing to do with the ringing of bells. We could, I suppose, think of a maritime bell, a buoy chiming to warn sailors from rocks, but that is not the kind of bell Dickens’s story describes. These are church bells, even though they are tolled by spirits, ‘goblins’, rather than Christian men and women. The bells toll Trotty to virtue, although these are not bells that Dickens cares to characterise in terms of their virtues.

Thus there grew up in the Middle Ages what were called the virtues of the bell. These were usually expressed in two or three words of Latin, and anywhere from two to twelve were inscribed on a bell according to its location, importance. and use. The best known are the three on a bell of 1486 at Schaffhausen, Switzerland, which inspired Schiller three hundred yean later to write his immortal poem, ‘Das Lied von der Glocke’, The Song of the Bell. The conciseness of the Latin gives a power which no translation can convey; VIVOS VOCO — MORTUOS PLANGO — FVLGVRA FRANCO (“I call the living; I wail for the dead; I break the lightning”) It will be seen that, from our present-day viewpoint, the virtues vary from the highly religious to the deeply superstitious. In the Middle Ages there was no clear dividing line between the religious and the non-religious. It was therefore quite natural that the inscription which mentioned such virtues as, “‘I praise the true God”, “I signal the sabbath”, “I note the hours”, “I arouse the lazy”, “I call for assembly”, “I weep at the burial” should also include “I torment demons”, “I drive away the plague” “I break offensive things”, and even, “I dispel the winds”, “I drive away the cloud”, “I break the lightning”, “I dispatch hail”, and “I extinguish fire”. [Percival Price, ‘Bell Inscriptions of Western Europe’, Dalhousie Review (1966) 423–24]

Why bells? Trotty has heard them, as he goes about his poorly-paid work, for years, but has in some obscure sense been untrue to them: he has ‘done [the bells] wrong in words,’ the Goblin of the Great Bell accuses him: ‘done [them] foul, and false, and wicked wrong, in words’. Trotty ‘confused’, denies it, and then says ‘it was quite by accident if I did’: but the bells press the point. It seems that Veck has wronged the bells by ‘lamenting’ his, and others’, poverty-stricken state.

‘Who puts into the mouth of Time, or of its servants,’ said the Goblin of the Bell, ‘a cry of lamentation for days which have had their trial and their failure … who does this, does a wrong. And you have done that wrong, to us, the Chimes.’

This seems incoherent: complaining is (a) wrong, and (b) a specific affront to church bells. What? If the idea is that church bells ringing is a tonation of celebration (as with wedding bells) then what of the funeral bell (Donne’s passing bell that tolls not just for the deceased but for thee) or indeed the wild tempest-driven shaking and cacophonous ringing that wakes Trotty on New Year’s Eve and sends him up the church tower? Why should the bells care if Trotty complains about his lot? He has much to complain about.

2.

Bells is the wrong vehicle for the story Dickens wants to tell here. But that’s alright: because there is an adaptation of The Chimes that finds a way of centring the bells, elaborating the story’s striking alternate-reality storyline—as surely, Dickens is the first writer to write alt-reality stories (the SF Encyclopedia suggests that Murray Leinster initiated this sub-genre in 1934, or else that the first was J-H Rosny aîné's Un autre monde (1895), but Dickens is decades ahead of them both). I’m talking about Frank Capra’s magisterial It’s A Wonderful Life (1946).

That It’s A Wonderful Life is an adaptation of Dickens’s Chimes—as Clueless is an adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma, or Apocalypse Now an adaptation of Heart of Darkness—is rarely, if ever, noted. But it is. Capra’s movie (and the Philip Van Doren Stern’s long short-story on which it is based) brings to the fore the protagonist’s suicidal ideation that is implicit in Dickens’s story. In It’s A Wonderful Life George Bailey, driven to despair, jumps into the river to kill himself—as Mary Furley did, as Meg Veck thinks of doing—and is saved only by the intervention of a trainee angel, Clarence Odbody (Dickens’s various goblins certainly have odd-bodies). Clarence shows George a world in which he had never been born, and in which all the people he loves and cares about are dead, or ruined, or miserable. It is part of the logic of the movie’s worldbuilding that angels must ‘earn’ their wings, by doing good in the world. One must assume these angelic apprenticeships are very common and successful since, as George's youngest daughter, Zuzu, says at the movie’s end: ‘teacher says every time a bell rings, an angel gets his wings.’ I once wrote a brief, seasonal short-story on this premise which you could read if you liked. Or not. I’m not the boss of you.

Anyway, the movie, though it substitutes one angel for Dickens’s myriad goblins, follows the lineaments of Dickens’s story: a decent man, who has worked hard all his life, trying to help his fellow humanity and care for his family, is driven to suicide by the pitiless realities of the economic world, and the heartless persecution of the wealthy; but that suicide results not in his death but instead a vision of an alternate version of the world—one much worse than even the miserable one in which he has been living—at the end of which he is restored to his family, his financial difficulties resolved and surrounded by the love of his fellows: and it happens to the sound of chiming bells.

This makes explicit what is, I think, implicit in Dickens’s original story: that Trotty climbs the church tower, full of self-reproach and self-hatred, as the bells ring and (as he thinks) rebukes him, in order to jump from the top and kill himself. In the work as printed Trotty gets to the top of the tower, sees the bells—but no goblins—and then abruptly ‘swoons’. What follows is a dream or (as per Dickens’s final paragraph) isn’t: but the implication is that Trotty jumps, that his body on the ground is his suicide. In It’s A Wonderful Life George Bailey jumping into the river can be retrieved—by Clarence, as Mary Furley was (though not her baby)—but somebody leaping from a tall church-tower onto the hard ground presumably could not. This in itself might suggest that Dickens’s ultimate ‘was it a dream? Or was it real and I am the dreamer? At any rate, be kind to people out there, in these hard times’ conclusion brackets both Trotty’s ‘Pottersville’ visions of the misery of all those he loves, and his ‘Return to Bedford Falls’ vision of happiness as dying, or posthumous, hallucinations. This is dark: darker even than the bracingly dystopian It’s A Wonderful Life. But that, I think, is the book Dickens has written.

Certainly suicide runs through it. Even though Trotty’s leap is implicit rather than explicit, the Mary Furley case Trotty reads about, and Meg’s path in the alternate-reality towards emulating her, are clear enough. One of the first things Trotty observes in the alt-timeline is a grand dinner thrown by Alderman Cut and Sir Joseph, interrupted by the news that a prominent banker has killed himself:

‘Deedles, the banker,’ gasped the Secretary. ‘Deedles Brothers—who was to have been here to-day—high in office in the Goldsmiths’ Company—’

‘Not stopped!’ exclaimed the Alderman, ‘It can’t be!’

‘Shot himself.’

‘Good God!’

‘Put a double-barrelled pistol to his mouth, in his own counting house,’ said Mr. Fish, ‘and blew his brains out. No motive. Princely circumstances!’

‘Circumstances!’ exclaimed the Alderman. ‘A man of noble fortune. One of the most respectable of men. Suicide, Mr. Fish! By his own hand!’

Richard drinks himself to death. Suicide is everywhere, because, I’d argue, the central event of the book is Trotty’s suicide, a death from which the bells-goblins somehow rescue him (or, perhaps, don’t).

Suicide is a strange theme to focus upon in a Christmas—or, more strictly, a New Year’s Eve—story. The Christmas season is about birth, new hope, redemption. For all that Dickens deprecates Peter Laurie’s insistence on prosecuting attempted suicides, he considers suicide is a mortal sin. Trotty’s epiphany involves an understanding that the young woman he was reading about in the newspaper, whose case decided him that the poor were ‘all Bad’—that is Mary Furley, but by extension his own child, Meg—acted from love, imperilling her own immortal soul by drowning her innocent baby and, thereby, sending it to heaven: ‘there is no loving mother on the earth who might not come to this, if such a life had gone before. O, have mercy on my child, who, even at this pass, means mercy to her own, and dies herself, and perils her immortal soul, to save it!’ It’s a strange mixture of condemnation and exculpation, this, turning an act of despair into a gesture of mercy: as if Meg is sacrificing herself to save her child. Montaigne said that ‘la mort est la recepte à tous maux’: death is the receptical for all ills. He also said that ‘Le vivre, c'est servir, si la liberté de mourir en est à dire’: Life is slavery if freedom to die is missing. [Montaigne, Essais (1595) 2.3.351]. Marzio Barbagli shows [Farewell to the World: A History of Suicide (Polity 2015)] that ‘for more than a thousand years in the West, suicide was ascribed to Satan’ to what John Sym in 1637 called ‘the strong impulse, powerfull motions, and command of the Devill’ but that in the nineteenth-century it began to be regarded differently: as a product of melancholy, or, as with Dickens’s novella, because of societal reasons—The Chimes anticipates Durkheim’s influentual Suicide (1897) in arguing that society was to blame. Dickens’s goblins are not demons or devils, prompting Trotty, or his daughter, to suicide; except that they perhaps look like they are. They are at once agents of a Christian redemption story and throwbacks to a pagan pantheon, holdovers from pre-Christian midwinter or soltice celebrations, the death of the old year (hence: suicide) and the coming of the new.

Still: suicide is a strange central topic for a Christmas book—or a Christmas film, like It’s A Wonderful Life. Perhaps Trotty’s logic, at the moment the Bells ‘convert’ him, is an attempt to see it as a kind of sanctified sacrifice, at (Meg’s eternal soul) great price—as the best sacrifice should be—for the sake of her young child, Christmas being the holy festival of the child. But that entails a strange, and indeed heretical theology. Dickens’s bells drowns out too careful or consecutive thinking about that! Ring out the old, ring in the new. Merry Christmas, everyone.