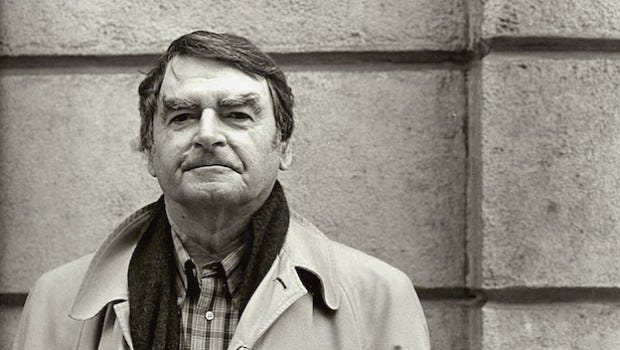

I was sorry to hear of the death of David Lodge, novelist and academic.

Looking back over his oeuvre, I discover that, with the exception of his first four novels (The Picturegoers [1960], Ginger You're Barmy [1962], The British Museum Is Falling Down [1965] and Out of the Shelter [1970])—to the which, for some reason, I never got around—I have read all his fiction and quite a lot of his criticism. This is, in part, a tell: since I am also an academic (and novelist), and Lodge’s highly-praised campus novels were major representations of university life across the 1970s and 1980s: Changing Places: A Tale of Two Campuses (1975); Small World: An Academic Romance (1984); Nice Work (1988)—all better, because funnier and wider-ranging, than Lodge’s friend Malcolm Bradbury’s sour The History Man (1975), although Bradbury may have been better served by TV adaptation than Lodge. The Academy is a different place today than it was then, and Lodge’s trilogy is now a period piece, but it remains excellent reading. His novelistic career was, perhaps, prone to ups and downs, as almost all such careers are. Paradise News (1991), a book about Catholicism and paradise and contemporary life, is not very good, although Lodge’s next novel, Therapy (1995) is excellent: it concerns a male mid-life crisis but, having stepped through a series of the kinds of comic scenes you might expect from such a topic, it takes a bracing and effective move into Kierkegaard, the philosophy of whom saves the novel’s protagonist. Lodge’s Henry James novel Author, Author (2004) was overshadowed by Colm Tóibín's frankly better Henry James novel, The Master (published a few months eatlier in the same year, and shortlisted for the Booker: Lodge later wrote about his experience of being literarily gazumped in The Year of Henry James [2006]). On the other hand, Lodge’s last novel A Man of Parts (2011), about the life of H. G. Wells, is much better than its reputation. It was criticised on publication because it spends so much time on Wells’s sex-life; but Wells’s sex-life was pretty much coterminous with his life as such, so that seems to me a viable approach to the topic. And Lodge is good on how this diminutive, small-headed, lower-middle-class man, with a high-pitched Cockney accent and various eccentricities, proved erotically irresistable to so many women.

This novel provided the only occasion on which I met Lodge personally, for I interviewed him for a public event at the British Library (on the grounds that I wrote a biography of Wells, and am vice-President of the H G Wells Society). Lodge was an excellent interviewee: he had the audience in the palm of his hand. Not every academic is a good lecturer, but—though I never actually saw him lecture—you could tell that he was one such. He also showed me his all-bells-whistles deafness aid, which he operated with an iPod; with it he could target his hearing throughout the room. Questions after the interview were fielded fluently. You wouldn’t have known he was deaf, though he was, and wrote about the condition eloquently in his 2008 novel Deaf Sentence. ‘I hate my deafness,’ he said, around this time. ‘It's a comic infirmity as opposed to blindness which is a tragic infirmity.’

I don’t mean to denigrate his achievement by suggesting that he had a particular talent for pastiche, although that was certainly part of his skill-set. He was immensely widely read in the anglophone novel tradition, as his extensive bibliography of literary criticism makes plain (Language of Fiction [1966]; Graham Greene [1966]; The Novelist at the Crossroads [1971]; Evelyn Waugh [1971]; The Modes of Modern Writing [1977]; Write On [1986]; The Art of Fiction [1992]; Consciousness and the Novel [2002]) and you can see elements of Greene and Waugh, of nineteenth-century fiction—playfully invoked and deliberately reworked in the Campus trilogy—in what Lodge did as a novelist. And here’s something else I came across, serendipitously (in the sense that I wasn’t specifically looking for it) the day after Lodge died. It’s Lodge’s pastiche of Craig Raine’s first ‘Martian’ poem, ‘A Martian Sends a Postcard Home’ (1979). That work is famous enough not to need summary, I think; but Lodge inhabits the Raineian-Martian idiom so expertly that what he lacks—originality—is more than made up for by the charmingly alienated perspective he provides, that of an older academic at a provincial university (such as I am) observing the going-on and doings of the rather incomprehensible young undergraduates he is teaching. The poem was published in the London Review of Books in 1984, and Clive James, no less, identified it as a kind of parody so well-done it unpicks the merit of its object: ‘David Lodge parodies the Martian approach so successfully that you wonder if it has quite enough to it’. What might have seemed a bold and brilliant new way of writing verse is actually a kind of gimmick, a trick that’s imitated with facility. Here is ‘A Martian goes to College’:

Caxtons are bred in batteries. If you take one from its perch, a girl

Must stun it with her fist before you bring it home.

Learning is when you watch a conjurer with fifty minutes’ patter and no tricks.

Students are dissidents: knowing their rooms are bugged, they

Take care never to talk Except against the blare of music.

Questioned in groups, they hold their tongues, or answer grudgingly, exchanging sly

Signals with their eyes under the nose of the interrogator.

Epilepsy is rife, and the treatment cruel: sufferers, crowded in dark and airless cells,

Are goaded with intolerable noise and flashing lights, till the fit has passed.

Each summer there’s a competition to see who can cover most paper with scribble.

The sport is hugely popular; hundreds jostle for admission to the gyms,

And must be coaxed out when their time is up. A few, though,

Seem unable to play, and sit staring out of windows, eating their implements.

And yet this is a good poem. ‘Caxtons’ (books) is a straight lift from Raine’s original, of course; although the notion of them in library-shelf ‘batteries’, and being stamped by the librarian on the way out (that used to be a thing, you know) is sharply observed. I am, as the contemporary idiom has it, seen, by Lodge’s description of lecturing as a fifty-minute and wholly empty conjuring trick, and I daresay students still play loud music in their rooms, go to clubs full of cacophonous music and strobe lighting to dance the nights away, and mumble and evade discussion in seminars. Sat exams in exam halls, where students scribble over endless sheets, or chew their pens meditatively, mostly stopped being a part of university life a while back, and the lockdown put an comprehensive end to it. Still, there is something of the estrangement of age looking at youth, and the way leaving home and going to university opens up odd vistas and perspectives on things. Excellent. We might wish he’d written more poetry.

Sad to hear the news! I loved The British Museum Is Falling Down -- extremely funny stuff and its brilliant use of pastiche did the great thing of giving one the feeling of being in on the joke.

Ahhh I'm gutted by this news--though he had a long and productive life, it still feels sad that all of his work is done.

I'd always meant to write him a letter saying how much I'd appreciated his endeavors (loved his novels--"Thinks..." is also a great read--and benefitted from his insights into the practice of writing) and I'd spent much time and money tracking down hardcover editions of all of his novels and much of his literary work.

Grateful for this notice and tribute from another writer whose work I've attempted to track down and collect in hardcover editions and whose work I've also enjoyed immensely!!