Blake's Laocoön

When is a draw not a draw? When it's a Jah.

The group-statue ‘Laocoön and His Sons’ was excavated in Rome in 1506, and immediately admired as one of the finest example of its type. Experts agree that it was sculpted around 200 BC, in Greece or Asia minor: Pliny says it was carved on Rhodes, by three sculptors he names as Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, but this is probably a guess or legend-reporting on his part.

The statue represents a moment from myth, most famously rendered in Vergil’s Aeneid, the demise of Laocoön, a Trojan priest. When the besieging Greeks left the wooden horse at the city gates, supposedly as a parting gift but in fact as a means of smuggling their troops inside, Laocoön refused to believe it, denounced it as a Greek trick (‘I fear the Greeks even when they bear gifts’, as Vergil famously has him saying) and even threw a spear into the flank of the horse in disdain—it reverberated, revealing that the structure was hollow, but the Trojans ignored this giveaway. Then a terrible omen persuaded them that Laocoön was wrong, and had offended the gods: two sea-serpents, with blood-red crests and fiery eyes, emerged from the sea, entangled Laocoön and his two young sons in their coils, devoured them, and then slunk away to the temple of Athena. The Trojans, terrified, immediately brought the wooden horse into their citadel, going so far as to dismantle their gateway to do so, the horse being so large. That night, the Greek warriors in the horse’s belly emerged, and the city was sacked.

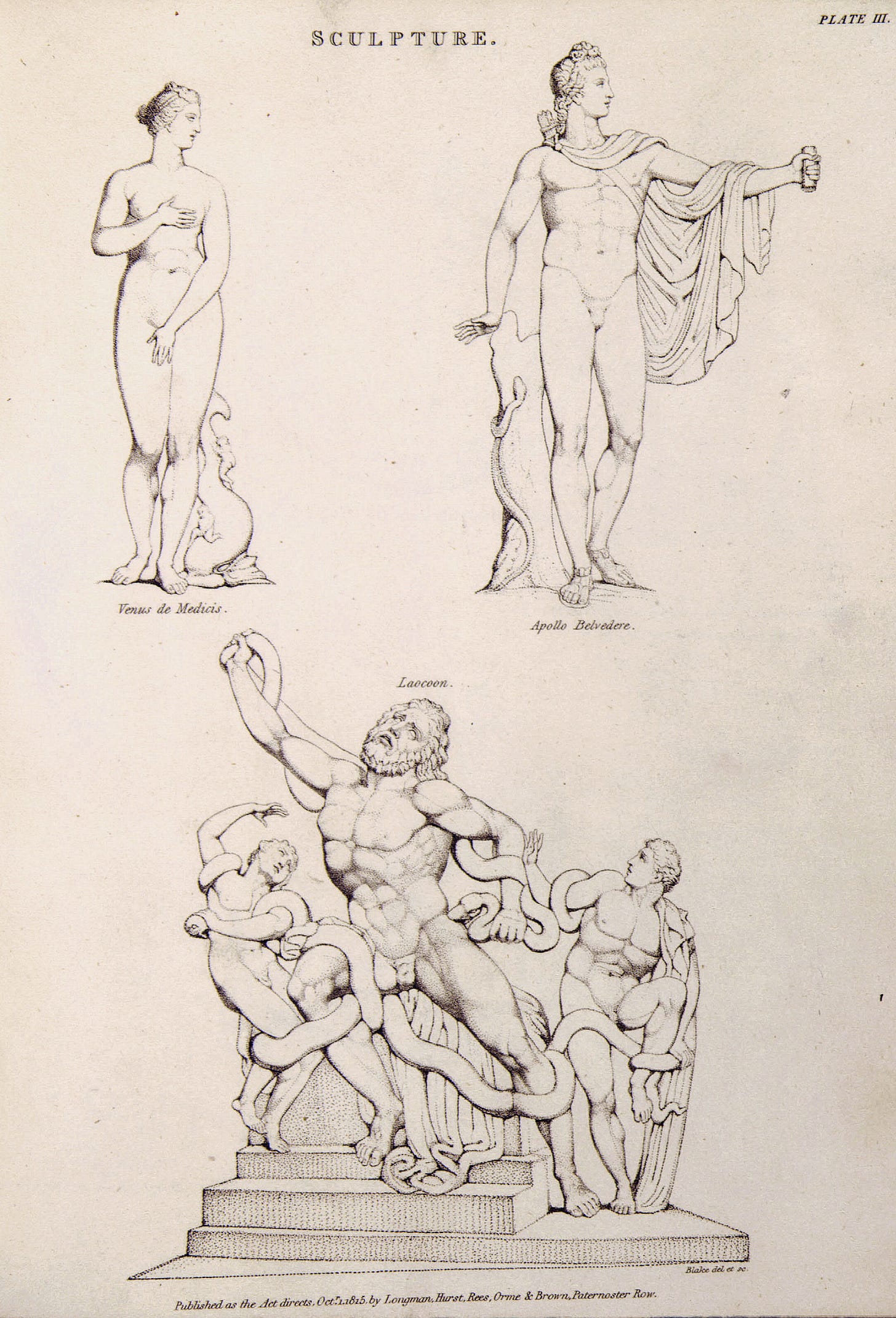

He surely knew it before, but Blake first paid the Laocoön statue proper attention in 1815 when his friend, Swedenborgian sculptor and artist John Flaxman, asked him to make an engraving of it (and some other pieces) for an article he was writing on classical sculpture for Abraham Rees’s Cyclopedia: or Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and Literature—an encyclopedia published in 39 volumes between 1802 and 1819. The actual Laocoön group is in the Vatican, a place Blake never visited (he never left England, and indeed except for one ill-fated expedition to the south coast never left London: the moral of that story being, never leave London) but a cast of the original is in the Royal Academy, and Blake went there to make sketches and prepare his engraving. Henry Fuseli, keeper of the Academy at that time, is supposed to have exclaimed: ‘vot, you here misther Blake? Ve ought to come and learn of you, not you of us!’ Here is the finished plate, as it appeared in Rees’s Cyclopedia:

Nicely done, this: clean, uncluttered, classical in the traditional sense. It gives a good sense of the dimensions and dynamic construction of the Laocoön sculpture, although there are a couple of suggestions of haste, or perhaps carelessness: the pediment is at once full-on to us and at an angle, the shading on the right thigh of the left-hand son is lumpishly done, and Laocoön’s penis is not so much fashionably de-emphasised, as per the cultural logic of the day, but actually absent.

The image well illustrates Flaxman’s larger argument: that sculpture, which had been more or less barbarous with the Egyptians and Babylonians, reached its first perfection of form and plastic expressiveness with the Greeks, and especially with what Flaxman calls ‘those precious monuments of art, the ancient groups’ (of which the Laocoön is the greatest) ‘in which we see the sentiment, heroism, beauty and sublimity of Greece existing before us’ [Rees’s Cyclopedia 32: 68]. For Flaxman ‘the essence of art is the imitation of nature’—a sentiment with which Blake, of course, violently disagreed.

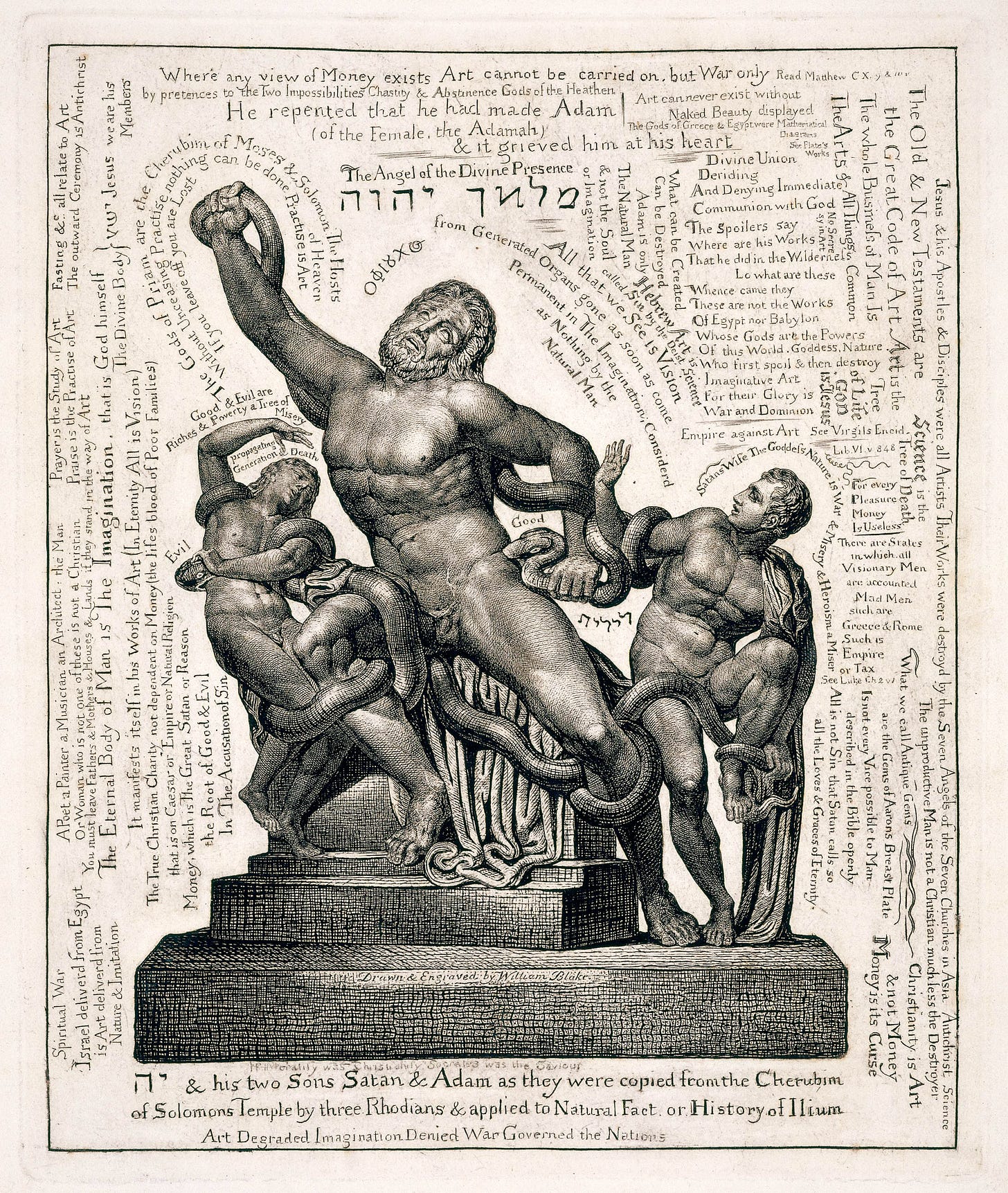

Blake was paid for his Cyclopedia work and went on to other jobs, but Laocoön wouldn’t leave his imagination alone. Some years later, at some point in the early 1820s, and it seems entirely for his own satisfaction—that is, not as a result of a commission, or even with the intention of printing and selling copies of the image commercially (although he certainly needed the money)—Blake re-worked his engraving of the Laocoön, added a blizzard of text around the figures, and printed a limited number of copies. We don’t know how limited the print run was, but indicative of its paucity is the fact that only two original printed sheets remain in existence today (the engraved plate has long gone): one is in the Fitzwilliam museum in Cambridge, the other in the private collection of Robert N. Essick, Altadena, California. If either were willing to give up their copy, I would be very happy to receive it. I might note that it’s my birthday in a few weeks.

It is, of course, simply extraordinary: the kind of image, like a Bosch canvas, Dadd’s Fairy Feller or Picasso’s Guernica, you can absolutely lose yourself in, immensely symbolically expressive although also challenging, busy, baffling, the visual iteration of limits at once contracted from a famous original and opaque to that original. The more I ‘read’ it, the more it becomes one of my favourite of all Blake texts.

The engraving is in part a rebuttal to Flaxman’s claim that there are ‘no works of sculpture discovered in any country at all to be compared with Greek art.’ Indeed, Flaxman styled the Hebrews as the enemies of art and sculpture: for him, the episode of the Golden Calf, and its implied critique of sculpture as inherently idolatrous, was ‘a dreadful attempt to annihilate inspired art at its birth’. For Blake, this was entirely the wrong way around.

The contrast between the image Blake made for Flaxman and the one he made for himself is striking. In the first instance Blake produced a clean, white engraving with lots of empty space; when he reworks this for himself he darkens the central sculptural group with minutely-worked textural specificity, making it more solidly situated and rounded; and he fills the white space with a horror vacui of words, inscribed into every space horizontally, vertically and surrounding the arm of Laocoön and the three heads like haloes. The writing is mostly in English, although one word is given in Greek—ΟΦΙ[ου]Χος, Blake’s idiosyncratic version, without accents or breathings as is typical when Blake cites Greek, of ὀφῐοῦχος: ‘snake-handler’ (from ὄφις, óphis, “snake” + ἔχω, ékhō, “to bear, carry, bring”)—and there are several pieces of Hebrew. Near the top is מלאך יהוה, ‘the angel of YHWH’, a phrase translated in the KJV as ‘the angel of the Lord’, for instance in Exodus 3:2–4:

And the angel of the Lord appeared unto [Moses] in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush: and he looked, and, behold, the bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed. And Moses said, I will now turn aside, and see this great sight, why the bush is not burnt. And when the Lord saw that he turned aside to see, God called unto him out of the midst of the bush, and said, Moses, Moses. And he said, Here am I.

Above this Hebrew Blake has written ‘the Angel of the Divine Presence’, his translation of the phrase. Below, by Laocoön’s left hand and underneath the snake (to which the word presumably applies) is, לילית ‘Lilith’. Originally a Mesopotamian storm demon, a bearer of disease and death, in the Rabbinical tradition Lilith was styled the first wife of Adam who left Eden after Adam refused to subordinate himself to her, and later coupled with the angel Samael. In some versions of the story she was a kind of night-devil, taking the form of an owl; in the Bible she is mentioned in Isaiah 34:14 as one of a group of monsters: the Vulgate for his passage translates the Hebrew Lilit as lamia, and so the female seductress demoness becomes serpentine in later traditions. That’s clearly revelant to the intimately physical, horrifically sensual central image of Blake’s engraving.

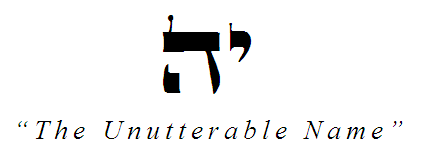

A third piece of Hebrew, at the bottom of the image, is יה, Jah, the shortened version of יהוה, Jahweh, the Hebrew God.

The William Blake Archive page on the image has a transcription (click on the ‘diplomatic translation’ tab) of all the English lines and phrase: the various aphorisms, assertions, claims and legends. I’m not going to go through every single word in the text here, but I want to talk about a few things with a view to trying to get more of a sense of what is going on in this striking image—why Blake produced it, why he didn’t try to sell it. What it is ‘about’.

A couple of things are clear enough. Most of all, as the legend at the bottom of the image makes plain, this picture is Blake repudiating the idea that the famous sculpture was original work by Rhodian Greeks illustrating the death of Laocoön. Not so, Blake says: this was a Hebrew sculpture, made for the Temple at Jerusalem by (or for, or modelled on) Cherubim, and only copied by the Rhodian Greeks, who misunderstood the true meaning of the work. The sculpture actually shows ‘[Jah] & his two Sons Satan & Adam as they were copied from the Cherubim/of Solomon’s temple by three Rhodians & applied to Natural Fact or History of Ilium’.

Blake’s engraving, then, reveals and glosses the ‘true’ meaning of the sculpture as Blake understood it: not a Greek priest strangled by the snakes sent by an angry pagan god or goddess (according to the mythological sources, the serpents came either from Poseidon, displeased that Laocoön had thrown a spear at the Trojan horse, or from Athena, who was deliberately misleading the Trojans in order accomplish the downfall of Troy, which town she hated). No, says Blake: the adult here is Jah, the God of the Old Testament, and the two youths are his sons, the dialectically-balanced Adam and Satan. The left hand snake has ‘Evil’ written over its head, and the right-hand one ‘Good’: but this is not to suggest that the image is picturing a battle between good and evil. Six decades before Nietzsche, and to rather different effect, Blake is taking us Beyond Good and Evil. As David E James puts it, the image does not allegorise ‘natural facts’ but sets out artistically to expresses spiritual truths. In Blake’s mythography, mankind—you and I—we all have fallen into an imprisoned, chained-up and miserable material existence. Release from this dilemma will come not through close attention to our materiality, the bricks of our prison, but through the emancipatory power of the imagination, the for Blake always spiritual and transcendent expressivism of the Artist practicing Art—as several of the aphorisms in the Plate record:

You must leave Fathers & Mothers & Houses & Lands if they stand in the way of Art.

Prayer is the study of Art.

Praise is the Practice of Art.

Fasting &c., all relate to Art.The Eternal Body of Man is the Imagination, that is,

God himself The Divine Body Jesus: we are his MembersIt manifests itself in his Works of Art (In Eternity All is Vision).

Jesus & his Apostles & Disciples were all Artists. Their Works were destroy'd by the Seven Angels of the Seven Churches in Asia, Antichrist Science.

The Old & New Testaments are the Great Code of Art.

Art is the Tree of Life.

Science is the Tree of Death.

The restrictions that pen and pin us have two limits, as-it-were horizons of being, an outer and an inner: what Blake calls ‘the limit of Opacity’ and ‘the limit of Contraction’. David E James [37] quotes a passage from The Four Zoas [from ‘Night the Fourth’, p56, 13-22] as illuminative of the Laocoön print. Jesus, discovering the fallen corpse of Albion, promises spiritual resurrection:

The Corse of Albion lay on the Rock the sea of Time & Space

Beat round the Rock in mighty waves & as a Polypus

That vegetates beneath the Sea the limbs of Man vegetated

In monstrous forms of Death a Human polypus of Death

The Saviour mild & gentle bent over the corse of Death

Saying If ye will Believe your Brother shall rise again

And first he found the Limit of Opacity & namd it Satan

In Albions bosom for in every human bosom these limits stand

And next he found the Limit of Contraction & namd it Adam

While yet those beings were not born nor knew of good or Evil

As James puts it: in the Laocoön engraving ‘the Imagination/Jesus complex of values, here identified under the term “Jah”, is projected onto the forms (Satan and Adam) in which it must enter space and time and confront materiality and reason’—that is, Blake’s oppressive and carceral ‘science’.

In the engraving the human figures are struggling to free themselves from the pair of serpents, which are together materiality and moral systems devoid of imagination—that is, in antinomian orthodoxy, they are together the system of good and evil, rather than one being ‘Good’ and the other ‘Evil’.

I can’t disagree with this, which chimes with Blake’s larger legendarium, his core beliefs about art and poetry, his marrying of heaven and hell, damning of braces and blessing relaxes, his human-form incarnationism and his belief that Biblical truth had been derailed by a crushing and misleading pagan, classical, neoclassical and now scientific tradition, Hebrew vision being swamped by classical allegory and a kind of materialist historism, what this engraving calls ‘Natural Fact’ and the ‘History of Ilium’. As against this Blake worked to establish, in his own practice, what James aptly calls ‘a Hebrew-Anglo-Gothic tradition’, one that could ‘provide the basis for a cultural revolution.’

But … there’s a part of me that finds myself itchy at this mode of approach to Blake’s engraving, and indeed to his art more broadly. It works to provide conceptual and interpretive coherence: it selects and rearranges details from Blake’s art and poetry to make the gorgeous, creative confusion—con-fusion—of the orginal comprehensible to precisely the rationalising mind that Blake himself abdured.

When I look at Blake’s Laocoön engraving I see a number of generative contradictions, as much formal and textual as to do with content and semantics. I don’t mean the ‘the trinity is God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit, not Jah, Adam and Satan!’ type of contradiction of orthodoxy: Blake is full of that, through all his work, and generally what he is doing there is attempting to shock people out of complacency and habit, trying to get them to rethink more imaginatively what they have been trained, by rote, to believe. I mean the more fundamentally expressive contradictions, out of which the true friendship of art can emerge.

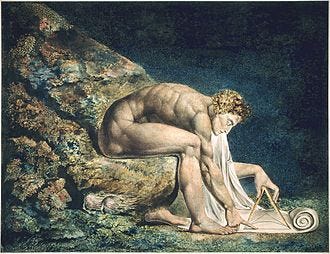

So: we could style the contrast in terms of visual texture between the two images as: neo-classical and Gothic, the one plain, harmonious and balanced, the other dark, dense, intricate and full of ornamentation, the curving lines of text over Laocoön’s arm and head looking almost architectural, like archways. This makes sense, as a Blakean artistic antithesis to the bald, bleached classicisim forced upon him by the Flaxman commission. But consider the image another way: the density, weight, the heaviness of image is more like the oppressive undersea pressures of Blake’s bottom-of-the-ocean ‘Newton’ (1790s, 1805), where the archpriest of ‘Science’ measures out reality with calipers, seated upon a great rock in such as way as almost to become part of it, the sisyphean crushing logic and limitation of materialist science …

… rather than like Blake’s many representations of the liberating fires of the imagination, the burning brush out of which the מלאך יהוה, ‘Angel of the Lord’ spoke thrillingly to Moses. Is that right for a text that speaks so multifariously and eloquently of escape, of transcendence, of art and imagination? Irene Tayler notes another potent contradiction:

The engraving used for Blake’s major plate [of Laocoön and his sons] is striking in its depiction of the depth, the mass, the solidity of the figures, as if one might turn the page around and see their sides and backs. But this three-dimensionality, established so firmly in the rendering of the statue itself, is then utterly subverted and denied by the rest of the plate—a crowded clutter of two-dimensional symbols that stand, by the most arbitrary of human conventions, for words and ideas. Editors have always had problems with the phrases and aphorisms because there is no progressive order in which to arrange them, no directive as to sequence, or even grouping.

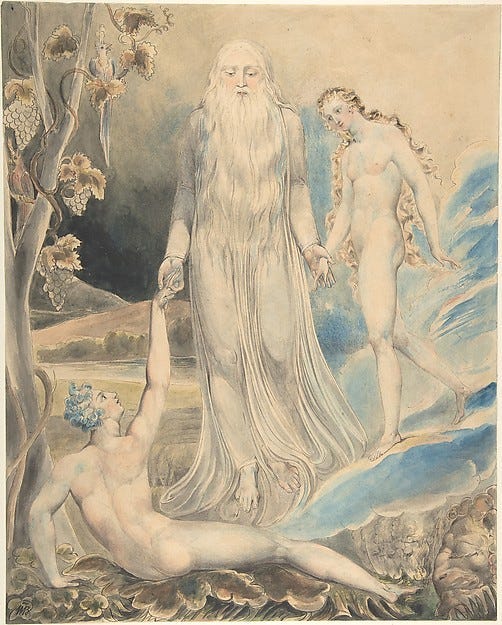

One thing Blake is interested in, here (and in his other art) is the way the shapes of words, in different languages—English carved out with deliberately careful neatness, Greek, Hebrew—form aesthetic constructions that augment or actualise their semantic meaning. This is why, though entirely autodidact where Hebrew was concerned, he was so attracted to inserting the expressive and lovely shapes of Hebrew letters into his art. Consider ‘Angel of the Divine Presence Bringing Eve to Adam’ (c. 1803), an engraving Blake made for his patron, the government clerk Thomas Butts:

The image riffs on Michelangelo’s creation of Adam, although instead of Adam’s hand connecting directly with Eve’s, both lovers are mediated by the ‘Angel of the Divine Presence’, this latter not God, it seems, but rather a divine emanation of angelic presence. Adam’s supineness, and Eve’s lightness of foot as she steps down, are both beautifully expressive. The vines signify fertility, and a lion lies down with a lamb peaceably in the bottom-right-hand corner. More: it seems obvious to me that Blake has modelled the arrangements of his figures in this image on the Hebrew letter שׂ, ‘shin’. In Jewish worship this letter stands for the word Shaddai, a name for God; and the kohen, or priest, forms the letter shin with his hands as he recites the priestly blessing (young Leonard Nimoy, observing this in synagogue when he was growing up, later used a single-handed version of the gesture as Spock’s Vulcan hand salute on Star Trek). Because it is so holy a letter, it is sometimes written with a special crown on the left hand upstroke.

We see the structural echo of this in Blake’s composition: the tree becomes the left hand upstroke, with the crown rendered as the foliate vine; the central upstroke the angel of the divine, the right-hand one Eve, Adam the bar across the bottom. It is a way of Blake saying, in effect: all these elements together constitute one holy name, God.

With the Laocoon Blake is constrained by the fact the central figures are what they are, how those ancient sculptors made them: but nonetheless I think he positions them centrally as יה, Jah, referenced above and below: Laocoön shoulders a horizontal line (not quite horizontal, but learning that way), his left arm and below that his body the vertical line, one son tucked underneath this shape, the other ornamenting it to the right. Laocoön’s raised left arm could be read as the ‘horn’ with which the name was sometimes spelled:

יה is also how ones says the number 15 in Hebrew (from י “ten” + ה “five”), although more devout Jews avoid this expression because of its proximity to the holy name of God. Was Blake aware of this? I note how often Blake’s aphorisms consist of precisely 15 words:

[Jah] & his two Sons Satan & Adam as they were copied from the Cherubim

Of Solomon’s temple by three Rhodians & applied to Natural Fact or History of Ilium

Good & Evil are Riches & Poverty, a Tree of Misery, propagating Generation and Death.

The Gods of Priam are the Cherubim of Moses & Solomon, the Hosts of Heaven

The Whole Business of Man Is The Arts, All Things Common. No Secresy in Art.

This might be coincidence, and plenty of the aphorisms here are not 15 words long: although 15 is three time five, and there are myriad threes and fives in the verbal, as in the visual, composition.

In what is still one of the most influential works of Blakean criticism, David Erdman’s William Blake: Prophet Against Empire (1969), the argument is made that the jumble of orientations, font-sizes and positionings of all the words in this image is a deliberate strategy to ‘collapse the temporal extension of verbal arts into the simultaneity of the pictorial’: ‘there is no right way to read them,’ said Erdman, ‘except all at once and as the frame of the picture’. I think this is right, except that the image is not ‘framed’ by the words: the image is a word (as well as a picture) and the words around it are pictures (as well as words). This is true, I think, not just in the individual shapes of letters and their combinations into words, but in the whole-view: it’s just gorgeous, the neatly folded and arranged lines of text, at once mimicking the engraver’s lines and stipples used to give a sense of shade and shape, and, I would argue, mimicking drapery in its shapes and pleats. Flaxman has a lot to say about the brilliance with which Greek sculptors replicated the way cloth fell and cleaved to bodies, the folds and particularities of drapery, and I find in Blake’s cape of words, thrown over the central statuary, a similar brilliance.

+++

Coda. Blake owned a copy of Dryden’s Aeneid, and in his Notebook for August 1807 he records undertaking the sortes vergilianae with it, opening it at random and putting his finger on a line to see if it told his fortune. The Vergil cited in this engraving isn’t quoted from Dryden’s version (it appears to be Blake’s own) but I have sometimes been struck by a Vergilian flavour of the passage at the end of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-3). Blake meets an angel who rebukes him and takes him into an underground chamber and shows him this hellish vision:

A cloud and fire burst and rolled through the deep, blackening all beneath so that the nether deep grew black as a sea, and rolled with a terrible noise. Beneath us was nothing now to be seen but a black tempest, till looking East between the clouds and the waves, we saw a cataract of blood mixed with fire, and not many stones’ throw from us appeared and sunk again the scaly fold of a monstrous serpent. At last to the East, distant about three degrees, appeared a fiery crest above the waves;[34] slowly it reared like a ridge of golden rocks, till we discovered two globes of crimson fire, from which the sea fled away in clouds of smoke; and now we saw it was the head of Leviathan. His forehead was divided into streaks of green and purple, like those on a tiger’s forehead; soon we saw his mouth and red gills hang just above the raging foam, tinging the black deeps with beams of blood, advancing toward us with all the fury of a spiritual existence.

The angel then leaves, and in his absence Blake finds himself ‘on a pleasant bank beside a river by moonlight, hearing a harper who sung to the harp’: the angel’s imagination had imposed upon Blake and obscured reality—Blake then reverses the situation, and forces his imaginative imposition on the angel. But concerning that monstrous sea serpent, and comparing it to Dryden’s version of the sea-snakes that attack and kill Laocoön.

Laocoon, Neptune’s priest by lot that year,

With solemn pomp then sacrific’d a steer;

When, dreadful to behold, from sea we spied

Two serpents, rank’d abreast, the seas divide,

And smoothly sweep along the swelling tide.

Their flaming crests above the waves they show;

Their bellies seem to burn the seas below;

Their speckled tails advance to steer their course,

And on the sounding shore the flying billows force.

And now the strand, and now the plain they held;

Their ardent eyes with bloody streaks were fill’d;

Their nimble tongues they brandish’d as they came,

And lick’d their hissing jaws, that sputter’d flame.

We fled amaz’d; their destin’d way they take,

And to Laocoon and his children make;

And first around the tender boys they wind,

Then with their sharpen’d fangs their limbs and bodies grind.

The wretched father, running to their aid

With pious haste, but vain, they next invade;

Twice round his waist their winding volumes roll’d;

And twice about his gasping throat they fold.

The priest thus doubly chok’d, their crests divide,

And tow’ring o’er his head in triumph ride.

With both his hands he labours at the knots;

His holy fillets the blue venom blots;

His roaring fills the flitting air around.

A parallel, I think.

It's a great art work with a thoughtful parsing. Very welcome in my day.

Thank you Adam, "...the image is a word (as well as a picture) and the words around it are pictures (as well as words)" is so insightful. I saw this recently in the Blake exhibition at the Fitzwilliam and the sense of the etching being done by hand -- carved out with indentations to the paper through the process is palpable.