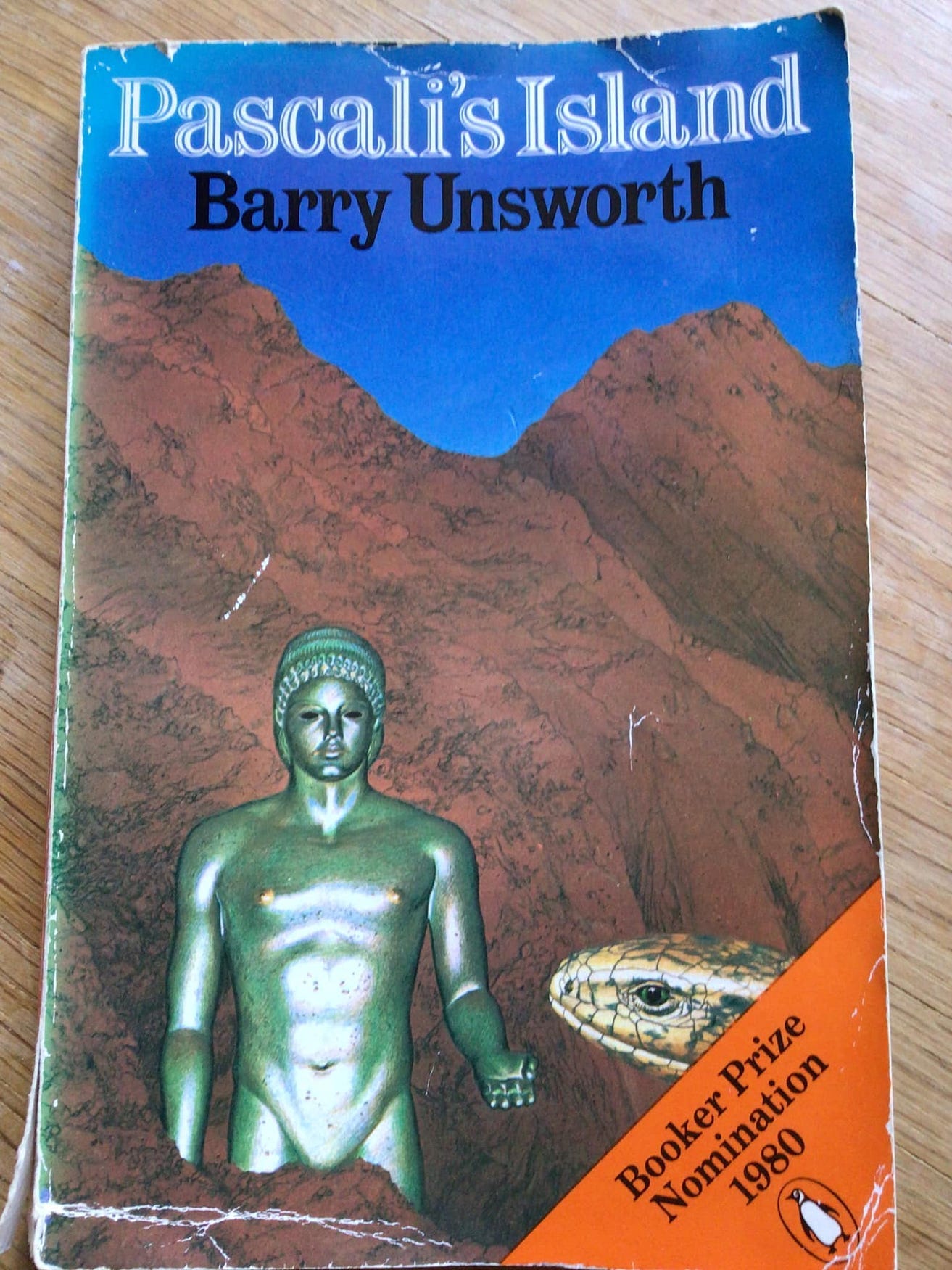

Barry Unsworth, ‘Pascali’s Island’ (1980)

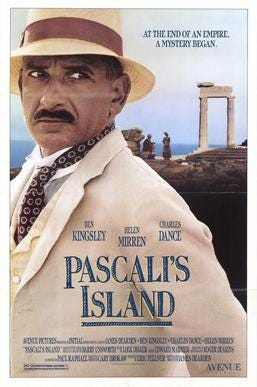

I read Pascali’s Island back in 1980, in this very tie-in paperback edition, where the positioning of the orange splash across the bottom right corner of the hardback cover art rather gives the impression of the Booker Prize as a serpent-headed entity. Which in a sense it is, perhaps. 1980 was the year Anthony Burgess’s superb Earthly Powers went up against Golding’s stilted Rites of Passage, the latter winning, contrary to natural justice — I talk about this here (scroll down). The shortlist that year also included J. L. Carr’s fine novella A Month in the Country, and future-Nobel-laureate Alice Munro’s The Beggar Maid (aka Who Do You Think You Are?), an excellent fix-up volume of linked short-stories. The other two shortlisted titles were Anita Desai’s Clear Light of Day and Julia O’Faolain No Country for Young Men. O’Faolain is one author on this list no longer current, no longer read. Unsworth may be another, I don’t know. He went on to win the Booker with his big slave-trade historical novel Sacred Hunger (1992) and through the 1980s and 1990s he was a big deal, but I don’t know if he’s still read, or discussed, or part of the critical debate, today. To read John Sutherland’s Reading the Decades: Fifty Years of the Nation’s Bestselling Books (2002) is to be struck by how few of the titles discussed have survived, have any kind of currency or presence today. Obviously, I — a novelist of small profile, with neither sales nor prizes to my books’ names — will be forgotten after I am dead, and assuredly before then too. But it’s striking the extent to which writers can enjoy huge success in their day, sales, awards, cinematic adaptations, how they can be fêted and treated as great voices, and still vanish utterly away after their death. Unsworth was a major writer towards the end of the last century: prizewinning, bestselling, many of his novels adapted into films — Pascali’s Island was made into a pretty good movie in 1988 (written and directed by James Dearden: Ben Kingsley played Pascali, Charles Dance the Englishman Bowles and Helen Mirren the Italian sculptress Lydia) —

— and Morality Play (1995), which was also nominated for the Booker prize, was filmed as The Reckoning in 2003. And the Booker-winning Sacred Hunger is in production as a TV mini-series. This last fact might suggest that Unsworth is still current, still read and talked about. I don’t know though.

Anyway, recently I reread Pascali’s Island, and also watched the movie. My memory of the initial reading (four and a half decades ago! I am old) was hazy, although some moments had stuck with me.

The novel is narrated by Basil Pascali, living on an unnamed island — one of the Dodecanese, presumably— that is part of the crumbling Ottoman empire. The action happens July 1908. Pascali is ambiguously Turkish and Greek, Muslim and Christian, bisexual, an outsider in the island community. His occupation is: spy and informer. For twenty years he has been writing reports and sending them to his Ottoman masters. He has heard nothing back, although his salary is paid monthly with absolute regularity — he complains that it is the same sum it was twenty years ago, eroded by inflation, that he is poor, that he lives in a one-room hut, that he can’t afford to replace his spectacles, to dress properly, to eat. But it is the lack of any response to his missives that troubles him most. Now he writes to the Sultan Abdul Hamid II directly.

You do not know me, Excellency. I am your paid informer on this island. One of them at least, for their may be others. Forgive this temerity of your creature in addressing you. I am driven to it. I can no longer endure the neglect of your officials. In spite of repeated requests no word has come to me from the Ministry, no single word of acknowledgement. Never. Not from the beginning. Twenty years, Excellency. I sit here at my table, in the one room of my house above the shore, on this island, far from Constantinople and the centres of power. I have calculated that this is my two hundred and sixteenth report.

This will be, he says, his last: he has intimations that ‘they’ will soon assassinate him: that is, the Greeks on the island, working towards independence, who will kill him as a spy. There are partisans in the mountains, supplied with guns by an American (Smith, whose boat is moored off the coast, on the pretence of sponge fishing), fighting for independence. The Ottoman Empire is crumbling. Pascali can read in the faces of the Greeks around him that he will soon be dead. He writes, describing all that he can see.

For a while, the novel does something interesting with this Malone Dies-y premise, and there are some lovely descriptive passages. This is what Pascali can see through his one window.

At present, because of the slight haze or graining in the air, only the nearer islands are visible: Spargos with its almost symmetrical bulk, the long jagged line of Ramni. Below me I can follow the sweep of the bay as far as the headland, and see beyond to the pale heights of the mainland across the straits. In the thickening of atmosphere, the sand and stones of the shore appear slightly smoky, as if enveloped thinly in their own breath. Beyond this is sea is opaline, gashed near the horizon by a long, gleaming line of light. The light fumes upward into the sky. The American’s caique will be somewhere out there, lying in that gash of light. [12]

Pascali goes out, returning home later in the day. Now his thoughts are running on extinction:

Now, back in my room, fear returns. Fear of the void to which I am moving. My words, the motion of my hand as it writes, alike proceeding to the void. Parmenides knew of this … Is not Your Excellency’s foreign policy, holding together a crumbling empire Empire, based on fear of the Void? For twenty years I have poured language in, trying to achieve a depth which would enable me to drown —

The sea is blank. Without mark or indentation anywhere. A fitting image for the void. [15]

Pascali’s wish is to leave the island, to travel to Stambul, recover all his previous reports and edit them into a single book. Which is to say: he is a writer, in the fullest sense, and Pascali’s Island is, amongst other things, a self-reflection by Unsworth on the writer as de facto spy, informer, outcast. But Pascali doesn’t have the money to leave. So he observes, writes, anticipates his own death (‘my room is securely locked at all times. But of course they will break in, sooner or later … broken man on the rough cross, his head down’). He several times refers to this coming death as a Christ-like sacrifice — ‘why have you left me here among my enemies, Excellency? Why have you abandoned me?’ [45] — with he himself as the Paschal Lamb, as indicated by his surname.

From somewhere near at hand, somewhere above me, the soft, plaintive bleatings of a sheep. I looked up but could not see it. The light hurt my eyes. Waiting on some balcony for the sacrificial knife. How far is it off now, the Sacrifice Festival? [57]

But a whole novel cannot be made of such passive musings, so Unsworth introduces a story. It’s a pretty good story, although slender: the handsome English gentleman Bowles arrives on the island — played in the movie adaptation by the young Charles Dance, very well cast— intent, he claims, upon archaeological exploration. There are ancient ruins here and there on the island, and the local story is that the Virgin Mary ended her days in an island house. Bowles hires Pascali as interpreter, in order to negotiate with the authorities, the corpulent Mahmoud Pasha and his skinny sidekick Izzet, for the rights to explore a particular stretch of coastal land. Bowles also has an affair with the sculptor Lydia, who lives on the island (young Helen Mirren in the movie, also very well cast). Pascali has long yearned, hopelessly, after Lydia, and now he yearns hopelessly after Bowles as well. Spying on them making love on the beach one afternoon, he gets so het-up he has to hurry off to the town baths, to pay for a hand-shandy from Ali the masseur (he can afford only one of these visits per paycheck, and always goes at the exact middle of the month: ‘“Merhaba effendim,” Ali says. “This is not your usual day.” “I could not wait,” I tell him.’ [97]).

Lydia drops out of the novel after this (the movie adaptation, wisely, gives her quite a bit more to do) but Pascali performs his interpreter’s work: Bowles offers a large sum for a temporary lease: 200 lira. ‘I should feel myself to be trespassing on the Pasha’s property if I had not paid a proper sum for right of access’ he says. Pascali cautions him: ‘but this is more than the land could be sold for — such an offer will make them suspicious’ and is overruled: ‘please do as I ask’. The Pasha and Izzet, greedily, accept. A contract is drawn up. This means that Bowles has legal access to the land, although he cannot remove anything from the site. But he is happy with this, or says he is: he only wants his name to be associated with any notable or valuable finds he uncovers, which would, in themselves, be donated to the museum in Constantinople. The Pasha posts soldiers below the piece of land to ensure nothing is smuggled out, and Bowles goes about his archaeological business.

But it’s a ruse. The trick is this: Bowles arrived on the island with a number of small antique pieces hidden in his luggage, a marble head, a golden one. After a few days he returns to the Pasha and Izzet and claims to have discovered these on the Pasha’s land. There are, he implies, many more. The greedy Pasha, fearful that the Englishman will indeed pass this treasure to the actual authorities in Istanbul, rather than allowing him to claim the site for himself to sell the treasures on the black market and so enrich himself, is hindered by the fact that Bowles has the lease. He offers to buy the lease back. Bowles agrees, but (‘naturally, in view of the inconvenience, the disruption to my research and so on’) for a much higher price than he originally paid: 700 lira. The Pasha agrees.

This, it seems, is a scam Bowles has played-out at various places. He arrives somewhere, offers an exaggerated sum for a lease on a field or hillside or valley, pays only a small part of this on deposit (saying that it will take a week for the rest of the money to be transferred from his London bank) — then reveals his faux finds to the local ruler, afterwards selling the lease back for a fortune, and moving on. In fact there’s nothing valuable on this particular site, but by the time the Pasha finds out the truth Bowles will be gone. But there’s a twist. Though most of the site is void of valuables, Bowles has stumbled upon a flawless bronze statue buried in the dirt — there it is, on the book’s cover, at the head of this post. Bowles becomes fascinated, obsessed with this treasure, abandons his usual scam and instead attempts to excavate it and spirit it away.

This brings us to the book’s denouement, its weakest part. Pascali discovers the truth (he rummaged through Bowles’ luggage on arrival and discovered the smuggled-in heads). Challenged, Bowles shows Pascali the statue, and promises him a large sum of money if he will keep quiet about his plans — for despite the presence of armed Turkish soldiers to prevent just such a thing he is going to steal it: Bowles has recruited the American, Smith, who brings rig and tackle from his boat. One night Bowles, Smith, Lydia and two of Smith’s men assemble move the statue. At this point the Turkish guards are dead — killed, I think, by Greek partisans, although this isn’t spelled out. But Pascali, driven, somewhat inchoately, by a belief that Bowles is double-crossing him, as well as his tangle of lust and shame, has betrayed the Englishman to the Pasha. He ends the story not as Christ, but Judas.

They came for me, Mahmoud Pasha himself and Izzet at his heels. Appropriate of course that I should lead them to him, perform the kiss. Twelve troops. We went in two boats across the bay. They had muffled the oars. We made no noise as we crawled along the rim of the bright sea, the shadowed hills to our right. [179]

Caught in the act, Bowles, Lydia and Smith are all shot dead. The statue is broken in the mêlée. Pascali finishes his narrative by insisting that their deaths have robbed him of any further desire to write. He no longer has any desire to go to Constantinople, and indeed says ‘I know it now. My reports have not been read. Worse, they have not been kept’ [188]. All has been for nothing.

The ending feels like a false step, a melodramatic flurry of action capping a novel that is not really interested in activity, but in passivity — again, as per the narrator’s surname — and contemplation. The shift from a sacrificial narrative to a Judasian betrayal narrative is awkward, too. Why does Pascali betray Bowles? It could, potentially, have been like Jim’s leap, a profound interrogation of the human motivation of what looks, on its surface, like counter-intuitive action. But in the event it is too overdetermined to work that way. So we have: [1] Bowles promises Pascali money to keep his statue-smuggling secret, but Pascali is convinced this is simply a lie, that Bowles will pay nothing and will abandon him (but after the betrayal Pascali returns to his one-room hut to find the money has indeed been delivered), [2] Pascali is in love, and lust, with Bowles, but knows he can never have him, admires and resents him in equal portions, and works out his psychological tangle by cutting himself free from the whole relationship (in the event, Bowles’ death at the hands of Mahmoud Pasha does not free Pascali of his complex of odi et amo desires); [3] a German businessman, Herr Gesing, is also interested in the land for which Bowles has a lease, but for vulgar commercial reasons, not reasons of classical civilisation and archaeology: the ground is, it seems, rich in bauxite, and Gesing plans commercial exploitation of this resource. Bowles’s lease prevents him going ahead with this plan and, for reasons that are obscure, instead of just waiting until Bowles’s lease expires and then bribing the Pasha himself, Gesing plots to get Bowles removed. It is to Gesing, rather than direct to the Pasha, that Pascali first goes — and Gesing also promises him money for his betrayal (money which is duly paid, although in the last pages Pascali says he will not avail himself of this: ‘the blood money from Herr Gesing I will not collect’ [188]). The novel ends with Gesing triumphant: ‘the preliminary surveys have been made. Yesterday, and again today, there were explosions of dynamite, resounding over the whole island. First fanfares of Herr Gesing’s Commerce and National State’ [188]. Why Gesing was in such a hurry, prepared to betray four fellow Westerners to their death, is not made clear. [4] Pascali was involved in a complex game with two people, Bowles and Lydia, who were themselves involved in complex and nefarious games, and his betrayal was a chess move to outmanoeuvre them. But this is undercut by Pascali’s admission, which this reader shares, that he never knew exactly what either of them were up to: of Bowles ‘I do not know, even now, what he proposed to do with the statue. Other than getting away with it, I don’t think he knew himself’; of Lydia likewise: ‘I should have known then. She was the victim of us all’.

It’s a muddle, a missed target where ‘impactful denouement’ is concerned. Fundamentally I think the issue is that Pascali’s Island (to repeat myself: as per its title) is a novel about sacrifice that Unsworth, in the final pages, wrenches into being a novel about betrayal. He presumably thought this a neat twist, but it negates the earlier heft of the novel. Most of Pascali’s Island is about the end of things, the Ottoman Empire dying, Pascali’s facing the finis of his life, the impending nothingness we all face, eventually: the novel’s epigraph is from Demetrius Capetanakis: ‘nothingness might save or destroy those who face it, but those who ignore it are condemned to unreality.’ Unsworth flirts with this unreality in his telling: early in the book, he has Pascali draw attention to ‘the predicament of the tiny, amber-coloured fly entrapped in the frond of my wrist hair … the fly struggles and swoons in this swamp, amid the miasmic exudations of my skin.’ But in fact ‘there is no fly, no actual fly. The fly belongs to the realm of fancy.’ It is introduced into the narrative, he tells the Sultan, ‘only as an image of my insignificance in your eyes’ [11]. Pascali returns to this in the penultimate paragraph of the novel, teasing his reader — the Sultan, us — with the thought ‘maybe none of this happened. Like the fly, the fly on my wrist, remember?’ [189] This, chimes with a thematic of sacrifice, of nothingness, in a way not true of the melodramatic plot-climax of betrayal, gunfire, death and disaster.

Adam Phillips considers betrayal as, in a strange way, a creative act. Betrayal makes things happen: the passion of Christ, and therefore the redemption of mankind, could not have happened without it. ‘If betrayal is one of the ways, or even the way, in which we change our lives,’ says Phillips, ‘perhaps we should talk not only of the fear of being betrayed, but of the wish, the willingness to be betrayed, and to betray.’ He gives the Bob Dylan example:

In 1965–66 the erstwhile folk singer Bob Dylan released a great trilogy of albums, Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, and set off on a world tour that would change popular music. At a now famous concert at the Manchester Free Trade Hall Dylan was playing his new electric and electrifying music when a disaffected folkie in the audience shouted ‘Judas’. Dylan responded by instructing his band to ‘play fucking loud’ what turned out to be an extraordinary performance of ‘Like a Rolling Stone’, a song about someone disillusioned by who they had become, a song about someone having to change. People had been wanting Dylan to be one thing when he turned out to be another, and they felt betrayed. By doing something new and unexpected, Dylan was Judas.

Here the betrayer is someone who wanted something to change; in retrospect we can see that what sounded like a betrayal was innovation. Something was betrayed to make something else possible. This Judas was bringing a new sound, a new vision. Being called Judas incited Dylan, released him into being the person he had become. He played the loud music even louder. He took on the role, and it freed him, for the moment. Dylan, like Judas, now had, in the words of the song, ‘no direction home’. You can do a lot of things with betrayal, but you can’t undo it. It feels irredeemable. To betray is to create a situation that there is no going back from.

This may seem a long way from the expiring Ottoman Empire, on the very verge of being overturned by the Young Turks, but Unworth’s focus in his novel is not on that change — and Pascali’s grubby, obscure betrayal in no way plays into that larger historical shift. Pascali avoids change: he will never leave his island, never track down his writing and make something of it, never escape. The final line of the novel — ‘Lord of the world. Shadow of God on earth. God bring you increase’ — is the same as the opening line, because the novel goes nowhere, offers no line of escape, embraces its decay.