Alice Oswald’s “Dart” (2002): Drowning in the River of Language

Jan Coo, Jan Canoe, Jan Kenosis

The idea was originally Coleridge’s, although he never wrote it, as was the case with many of his proposed ideas and projects. In 1797 Coleridge planned a book-length poem, to be called The Brook, which would trace in verse the course of a West Country river—he doesn’t name the Dart, but it could easily have been that one—from source to sea, noting and versifying the nature, communities and incidents along its flow. In the Biographia Literaria (1817) he recalls this abortive project:

I sought for a subject, that should give equal room and freedom for description, incident, and impassioned reflections on men, nature, and society, yet supply in itself a natural connection to the parts, and unity to the whole. Such a subject I conceived myself to have found in a stream, traced from its source in the hills among the yellow-red moss and conical glass-shaped tufts of bent, to the first break or fall, where its drops become audible, and it begins to form a channel; thence to the peat and turf barn, itself built of the same dark squares as it sheltered; to the sheepfold; to the first cultivated plot of ground; to the lonely cottage and its bleak garden won from the heath; to the hamlet, the villages, the market-town, the manufactories, and the seaport. My walks therefore were almost daily on the top of Quantock, and among its sloping coombes. With my pencil and memorandum-book in my hand, I was making studies, as the artists call them, and often moulding my thoughts into verse, with the objects and imagery immediately before my senses. Many circumstances, evil and good, intervened to prevent the completion of the poem, which was to have been entitled The Brook.

Three centuries later, Alice Oswald supplied the poem Coleridge planned but didn’t write, with Dart (2002) her book-length work tracing a west-country river from source to sea, encompassing along its flow the variety of Devonshire natural and artificial life. Oswald is not from the west country, as Coleridge was (she is from Reading); but she lives in Totnes, at the mouth of the Dart, and knows the area well. For this poem, as the note at the beginning of the volume says, she spent ‘two years recording conversations with people who know the river’: the finished poem sometimes quotes from these interviews verbatim, sometimes reworks or consolidates them, ‘using them as life-models to sketch out a series of characters.’ This is well done, I think: these Darty monologues are all differentiated, the speakers distinct and well-characterised, the particularity of their various voices captured; and even without the steer of marginal glosses identifying them (‘the walker replies’, ‘naturalist’, ‘fisherman and bailiff’ and so on) it’s easy enough to see where, as we might say, the Eliotic police are doing their things in different voices. Easier than Woolf’s The Waves, for instance. This pulse, stretches of poetry—free verse, rhymed stanzas (usually half-rhymes rather than full-), lyric moments, one ballad—alternating prose ‘voices’, is the larger form of the piece.

Though Coleridge never finished The Brook, there are various fragments of it in his notebooks. These, isolated and printed together, bear an interesting resemblance, and specific specific textual relation, to Oswald’s poetic bricolage. Here’s Coleridge:

The swallows interweaving there mid the paired Sea-mews, at distance wildly-wailing.—Theabrook runs over Sea-weeds.—Sabbath day—from the Miller's mossy wheel the waterdrops drippd leisurely—On the broad mountain-top The neighing wild-colt races with the wind O’er fern & heath-flowers—A long deep Lane So overshadow’d, it might seem one bower— The damp Clay banks were furrd with mouldy mossBroad-breasted Pollards with broad-branching head.Moths in the moonlight.—

This could very easily be a section of Oswald’s Dart, as it stands (though she would say ‘over’ and ‘overshadowed’ rather than ‘o’er’ and ‘overshadow’d’). These elements are all in Dart—birds, plantlife, the landscape, roads, clay, moss, waterfowl—and the scheme of using the trajectory of the river to thread together observations of the natural world, the people who live and work this landscape, and what we might call ‘thoughts on humankind’ are reproduced. This is by way of saying that Dart is, in a sense, a Romantic poem, which I think it is.

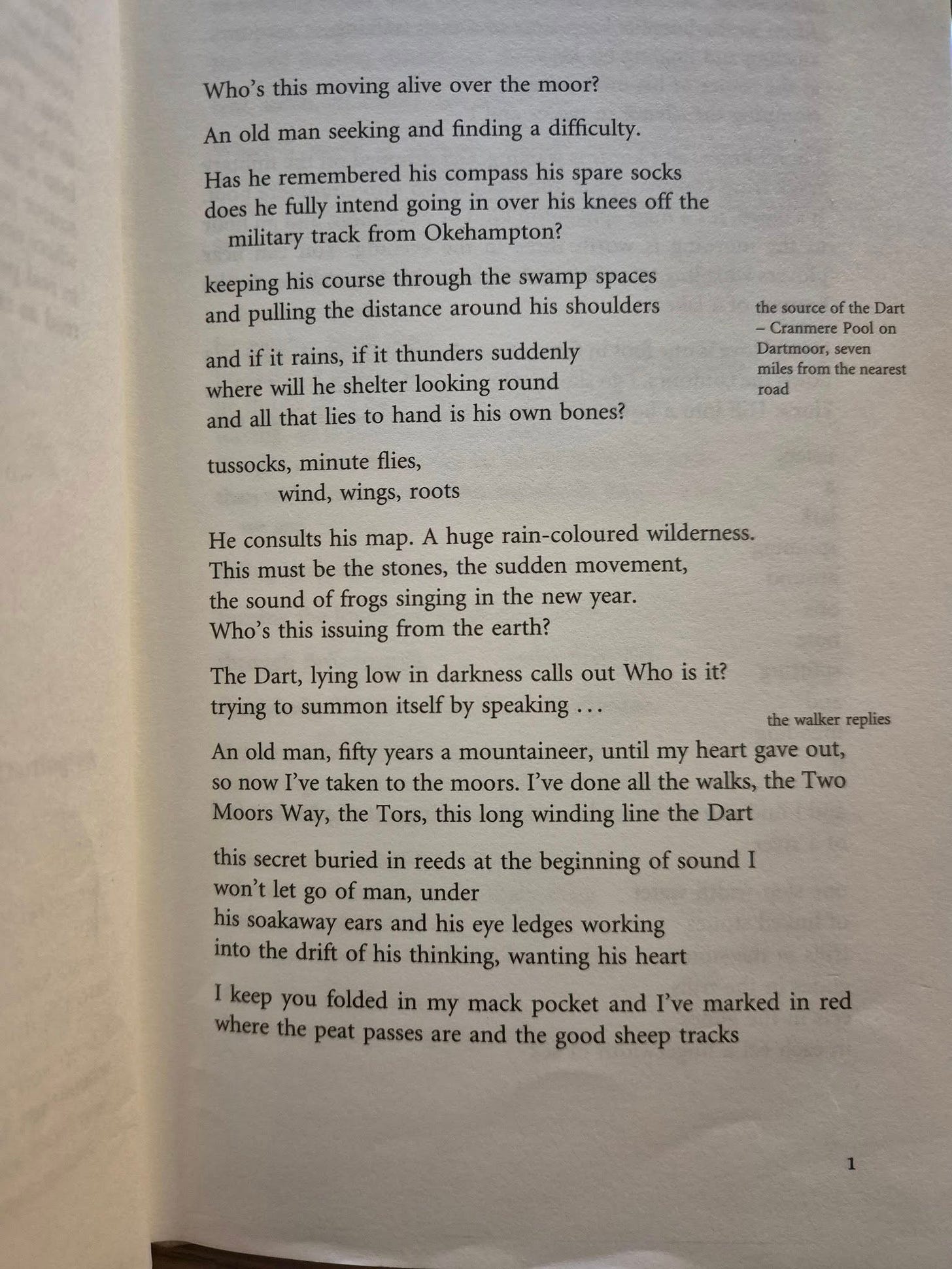

Here’s how Dart begins:

The marginal glosses, there, are present throughout, guiding the reader in terms both of the topography of the river, and the mythic and riverine significance of the figures encountered. They look somewhat like the glosses Coleridge added to The Ancient Mariner in 1816—another poem about water and flow and mystery, about (as is Dart) the compulsion to move on. I suspect this wasn’t unintentional on Oswald’s part. When it was published, reviewers mentioned Eliot and Ted Hughes as influences, but it seems to me that the poem is, in a deeper sense, Coleridgean.

An Account of Dart. I haven’t counted them exactly, but I’d say the poem is something over 1300 lines long—not all that long, as epics go—running to 48 pages in the Faber edition. There’s a pause more or less halfway, a blank page split between the bottom half of p.21 and top of p.22, in which the only notation is the small-font singleton ‘silence’ (this marks the death by drowning of one of the ‘characters’ of the piece; other characters also drown, but don’t get this respectful silence. So it goes). The poem, as I mentioned, alternates sections of original poetry with sections based on Oswald’s interviews with actual Dartmoor people, all connected with the river in some way. These chunks of reportage are sometimes versified (lightly so, I’d say: though it’s hard to know without the original transcripts) and sometimes laid-out in prose. Marginalia identify the speakers. In between the implied speakers are flora and fauna, people and spirits, ghosts and gods, mythic figures and anthropomorphisations—not least the figuring of the river itself as a person, with its own voice, or voices, and the blurring of the human agents and patients into the rush and hush of the river’s vocalisations. Dart stands out, says Timothy Clark, ‘as a text in which a less anthropocentric sense of reality is projected by formal techniques that refuse the domination of the text by one linear narrative or point of view’ [Timothy Clark, The Value of Ecocriticism (CUP 2019), 67]. So although many anthropoid speak in this poem, the poem as a whole can be considered as a dramatic monologue in which the overarching speaker is non-human: the river itself.

Dart opens on a walker, ‘an old man, seeking and finding a difficulty’, who must be in his late sixties or early seventies (he says he was ‘fifty years a mountaineer, until my heart gave out,/so now I’ve taken to the moors’). He talks of his pleasure walking this landscape, and itemises what’s in his rucksack: ‘spare socks, compass, map, water purifier … tent, torch, chocolate, not much else’ [3]. He is present at the start of the poem, and the start of the river, ‘the source of the Dart—Cranmere Pool on Dartmoor, seven miles from the nearest road.’ He walks along the river, encountering another figure, saying ‘I know you,/Jan Coo. A wind on a deep pool’ [4] The marginal gloss tells us that Jan Coo is an avatar of the Dart itself, as the Iliad anthropomorphises the Scamander as a humanoid form who rises up to tell Achilles to stop throwing dead bodies into its flow. ‘Jan Coo, the name means So-and-so of the Woods, he haunts the Dart’ [4] says the marginalium. The name of the river, Dart, derives from the pre-Roman native word for ‘oak’. The river, surrounded by oak forest, oak trees that draw their water from the flow. At Postbridge, ‘where the first road crosses the Dart’, there is the first mention of pollution, in the voice of the river, or of Jan Coo: ‘Oh I’m slow and sick/There’s roots growing round my mouth, my foot’s/In a rusted tin [4].

Jan Coo is ‘the groom of the Dart’, drowned in and joined to the water, ‘he’s so thin you can see the light/through his skin, you can see the filth in his midriff’. But he’s also separated: ‘a white feather on the water keeping dry’. The backstory here is that a young cow-herder (hence his surname) kept hearing a strange voice on the wind, calling him; one day he went off onto the moor to find out who this was, never returned and was later found drowned.

Then the poem gives us the second of Oswald’s ‘recorded conversations’, this time with a naturalist, whose intimacy with the Dartmoor wildlife comes across as almost creepily sexual and predatory:

I’m hiding in red-brown grass of different lengths, bog bean, dundew, I get excited by its wetness, I watch spiders watching aphids, I keep my eye in crevices, I know two secret places, call them x and y where the Large Blue Butterflies are breeding, it’s lovely, the male chasing the female, frogs singing lovesongs. [5]

Then some vividly-phrased observations: an eel ‘strong as a bike-chain’, other eels ‘tumbling away downstream looping and linking’, the Dart passing beneath a bridge in the sunlight, ‘endlessly in motion as each wave/photos its flowing to the bridge’s curve’ [6]. You have to admire Oswald’s verbal craft in all this, and again as the speaker (still the creepy naturalist? I’m not sure) says:

I let time go slow as moss, I stand and try to get the dragonflies to land their gypsy-coloured engines on my hand

which is a gorgeous triplet. Then two full pages of adapted recorded interview with an angler (‘I’ve paid fifty pounds to fish here and I fish like hell’) and we move downstream to where the West Dart joins the river. ‘The West Dart,’ the marginalium informs us, ‘rises under Cut Hill, not far from the source of the East Dart’. When Oswald says

(meanwhile the West Dart pours through Crow Tor Fox Holes …) [9]

—we recognise the nod to Ted Hughes (Crow, ‘The Thought Fox’) although I don’t doubt these are also Dartmoor locations. Hughes’s volume River (1983), one of his major works, was surely an influence on Oswald’s work—it’s another book length poem tracing the course of a West-Country flow, and contains a poem specifically called ‘The West Dart’.

Oswald steps carefully around specific intertextual allusion, or quotation, but this is a very Dart-ish piece of verse. ‘The West Dart speaks a wonderful dark fall’ is what Oswald says [10]. It is hardly controversial to suggest that she has been influenced by Hughes. The memorial, supposedly secret but now on Google Maps, to Hughes placed near the source of the West Dart postdates this poem, of course. But the Dart was a river special to him, and Oswald is in many respects a Hughesian poet: vivid and raw, free with form but always alive to the specific rhythms of the poetic line, with a superbly muscular, penetrating turn of phrase: both are poets engaged by, immersed in, Nature, poets energised by the force that through the green fuse drives the flower—flower, as in plant, flower here (as the cryptic crossword setters like to say) meaning river, the thing that flows. Hughes, in turn, was passionate about Coleridge: his Faber Selected Poems of Coleridge (1996) comes with a vast, sprawling introduction itself the length of a short book, that goes into Coleridge’s verse in immense, passionate, sometimes bonkers detail.

Then again whilst there are similarities between Oswald and Hughes, but there are differences too. The last word of Hughes’s ‘West Dart’, there, is one: Hughes sees, in the vivid haecceitas of the natural world, portents, meaning, intensities of signification prophecies and wonders, and it means that his verse, much as I love Hughes, is sometimes portentous in a bad sense: windy, vatic, pompous. Oswald’s verse is never those things: she sets out to capture natural things as themselves, not as portents. In his many river poems, as Susanna Lidström notes, ‘the river creatures, more than anything else, act as Shamanic guides for Hughes, drawing him through the sliding “water-mirror meniscus of the river’s surface into the deep, fluid Otherworld of imagination’ [Lidström, Nature, Environment and Poetry: Ecocriticism and the poetics of Seamus Heaney and Ted Hughes (Routledge 2013), 117]. Oswald’s is not so wedded to the old Wordsworthian egotistical sublime as this. She is a gardener, not a shaman; she cultivates and curates, she observes and notes down with a fineness of verbal apprehension and hyperrealist vividness of phrase-turning. But in this, we could say, she is the more Coleridgean—not the Ancient Mariner-Kubla Khan-Christabel Coleridge that so engaged Hughes, but the Coleridge of ‘Frost at Midnight’ and ‘Lime Tree Bower’, and especially of his great prose epic of precision-tooled close-attentiveness to the thingness of things, Coleridge’s Notebooks. There’s a lot more I could say about this, but I’m gone on long enough already, and, as another once said, miles to go before we sleep.

Now Dart introduces a forester (‘here I am coop-felling in the valley’) who is addressed, though I suspect he doesn’t hear her, by a water-nymph:

woodman working on your own knocking the long shadows down all day long the river’s eyes peep and pry among the trees …woodman working into twilight you should see me in the moonlight comb my cataract of hair at work all night on my desireoh I could sing a song of Hylas how the water wooed him senseless [11]

This classical pastoral trope, the demigod tempting the mortal to his doom, the half-rhymes actualising the half-connection between nymph and woodsman. Perhaps he will hear her song, but the poem is moving on.

… to a section addressing ‘O Rex Nemorensis’: eleven 3-line stanzas, 3-stress per line, which a marginalium glosses as ‘the King of the Oakwoods who had to be sacrificed to a goddess’. In fact, as James Frazer’s Golden Bough discusses at length, the rex Nemorensis was the priest of the goddess Artemis-Diana at Aricia in Italy, by the shores of Lake Nemi (hence ‘king’ of Nemi). ‘The priest was king of the sacred grove by the lake. No one was to break off any branch of a certain sacred oak, except that if a runaway slave did so, he could engage the Rex Nemorensis in mortal combat. If the slave prevailed, he became the next king for as long as he could, in turn, defeat challengers.’ Frazer sees this as the protomyth, the old lame king being killed and replaced by the new young king, as the old year dies in winter and the new year is born into spring and fertility. The speaker here, presumably the Dart itself, praises the trees after which it is itself named: ‘Oaks whose arms/are whole trees’, laments the drowned and then spots a ‘canoeist/just testing his/strokes in the/quick moving river’, which leads to a prayer, the connection being the associationist resemblance, I suppose, between the tapering orange-red shape of the canoe and a flame:

O Flumen Dialis let him be the magical flamecome spring that lights one oak off the nextand the fields and workers bursting into light amen

Not a forest fire, but the rebirth of the forest in the spring sunlight. ‘Flumen Dialis’ is a kind of pun: in Ancient Rome the ‘Flamen Dialis’ was an important priestly role: Dialis being a worn-down version of Diespiter, the old name for Jupiter—it’s equivalent to dies pater, God the Father—and flamen meaning ‘priest’, a word that is perhaps connected to flamma, ‘flame, fire’ (as in: keeper of the flame, perhaps). Oswald shifts flamen to flumen, river.

This leads into another of Oswald’s interview transcripts, with a canoeist, enthusing about their hobby, or sport. They are doomed though—the marginal note tells us that they drown, wedged between rocks and on their side (whether this means Oswald interviewed a canoeist who afterwards died, or whether she interviewed a canoeist and then segued his still-living words with another boater who perished, I don’t know). The poem styles this section almost as a siren song: ‘put your head under the sloosh gates’ the river urges the canoeist. ‘It looks a good one, full of kiss … come roll it on my stones,/come tongue-in-skull, come drinketh, come sleepeth’. Then the canoeist:

I was pinioned by the pressure, the whole river-power of Dartmoor, not even five men pulling on a rope could shift me. It was one of those experiences – I was sideways, leaning upstream, a tattered shape in a perilous relationship with time.

The ‘come drinketh, come sleepeth’ is from an old proverb: ‘he that drinketh well sleepeth well and he that sleepeth well thinketh no harm’; or more elaborately: ‘he that drinketh well sleepeth well and he that sleepeth well sinneth not, and he that sinneth not goeth straight through Purgatory to Paradise’. The siren’s call: some, sleep the sleep of paradisical death. No sleep is deeper.

Then the poem moves om to some ‘town boys’, poking the iced-up river with sticks, poaching a salmon that happens ‘to flip out right onto the stones’. Then in prose: another of Oswald’s interviews of locals, this time a tin-extractor. Then a woollen mill:—this last, Buckfast Spinning Mill, a going concern when Oswald wrote her poem, and with (as her marginalium records) ‘a licence to extract river water for washing the wool and for making up the dyes’ [19]. It was run by Axminster Carpets for many years, but a facility that went into receivership in 2013 and closed down. It is presently unoccupied.

Then another found poem (in quotation marks) by Theodore Schwenke, who observes the river, ‘whenever currents of water meet the confluence is always the place/where rhythmical and spiralling movements may arise,/spiralling surfaces which glide past one another in manifold winding and curving forms …’) morphing into the last words of John Edmunds, who drowned in the river in 1840: his cries for help (if I shout out/if I shout in/I am only as wide/as a word’s aperture’) and then, after a strangely specific eighty seconds, his death. Here the poem pauses, marking the silencing of his voice with two half-pages of empty space.

After the hiatus the two blank half-pages pp 21-22, there’s a swimming scene:

He dives, he shuts himself in a deep soft-bottomed silence which underwater is all nectarine, nacreous. He lifts the lid and shuts and lifts the lid and shuts and the sky jumps in and out of the world he loafs in.

Arrestingly, this styles the river as a kind of box—do we think ‘coffin’?—with the surface-tension of the top of the water a ‘lid’, and the swimmer inverting the usual distinction of sky and underwater: such that the swimmer repeatedly surfacing into air is the sky ‘jumping in’, like a fellow swimmer. This is soft (the silty ‘soft-bottom’, the laziness of loafing), although this same swimmer is sharing the water with the memory of the drowned, rendered according to the logic of materialization that is the flow of the poem, as if they are physically copresent.

What’s this beside him? Twenty knights at arms capsized in full metal getting over the creeks; they sank like coins with the heads on them still conscious between water and steed trying to prize a little niche, a hesitation, a hiding-place, a breath, helplessly loosening straps with fingers metalled up, and the river already counting them into her bag, taking her tythe. [23-4]

The marginalium at this point is: ‘Dart, Dart, wants a heart’, an ancient Dartmoor proverb or saying (also recorded as ‘Dart, Dart, cruel Dart, every year thou claim’st a heart’) referring to the many who have drowned in the river (Perceval in John Boorman’s Excalibur, knocked into the river by mad Lancelot, discarding his armour piece by piece in the green-murky waters until he is in his underclothes and can rise to discover the holy grail). The h-alliteration here, replicating the panting of the drowning knights, is perhaps a touch over insistent (heads-hesitation-hiding-helplessly, following the k-choking capsized, creeks, coins, conscious and followed in turn by the stutter of meTalled-taking-tythe). More, the dream, if that’s what it is, of these chivalric figures is confused by the metaphysical conceit of the sinking coins: ‘the heads on them still conscious’ may refer to the knights, whose heavy helmets weigh them down, or might indicate the surreal notion that the heads-verso of coins comes alive in the water. I don’t know why Oswald spells tithe with a y. I don’t know y Oswald spells tithe with a why.

Two more victims of drowning are mentioned (‘Poor Kathy Pelham’, and an unnamed scout—a boy scout? A ranger? It’s not clear) and then we’re back to recorded testimony, the account of a ‘water abstractor’, involved in testing and purifying the water at Littlehempston pumping station, who lists the various contaminants in the flow (‘acids and salts/ Cryptospiridiom smaller than a fleck of talcom [sic] powder … black inert matter’: he ‘adds more chlorine’). Then the river shifts suddenly from fresh to salt water: we’re at Totnes Weir where ‘the river meets the Sea’ [26]. The weir is about a mile north of Totnes, and the sea proper, but the channel-waters backwash this far, and the flavour of the poems shifts with it. This is more than just a matter of a different water, a tidal logic, salt-marks on the plantgrowth (‘bangles of brash on branches’ [27] the poem alliterates) and different fauna: saltwater fish, crabs, seabirds (‘a swim of seagulls, scavengers, monomaniac, mad/rubbish pickers, mating blatantly, screaming’ [29])—it is also marked by a loosening of the structure of the poem, an enlargement of the poem’s flow. Where the early sections of the poem reproduce the tourbillons and cross-currents of the early river, the later section washes in and out in larger units: there’s a dream recorded in five 12-line stanzas, saltily half-rhymed (abbaccddeeff) rather than fully chiming their line-endings. Here is the second stanza of those five: a flock of seagulls flying up into a crescent-moon sky at evening, and landing again:

I saw a sheet of seagulls suddenly flap and lift with a loud clap and up into the pain of flying, cry and croup and crowd the light as if in rivalry to peck the moon-bone empty then fall all anyhow with arms spread out and feet stretched forward to the earth again. They stood there like a flock of sleeping men with heads tucked in, surrendering to the night, whose forms, from shoulder height sank like a feather falls, not quite in full possession of their weight. [27]

‘Pain of flying’, presumably, because the seagulls are making such a loud complaining noise. The weakest line here is ‘they stood there like a flock of sleeping men’ (flock is a dull word for, well, a flock of seagulls; and the comparison is stymied by the fact that men don’t stand to sleep), but a ‘sheet of seagulls’ is nicely put, and the final couplet is gorgeous.

Then another of Oswald’s interviewees, a worker in a dairy, talking at length about milk-processing and bottling (‘I’m in milk, 60,000,000 gallons a week’ [29]). After two pages of this the poem switches to a rough ballad metre for an 18-stanza poem about the arrival in Britain of Brutus. Oswald works this ballad out of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, which describes how Brutus left burning Troy and, after many adventures, came to Albion with his crew, landing on the coast at Totnes (Totonesium litus—‘the littoral of Totnes’) where they encountered the land’s only inhabitants, giants. These tallboys are descendants of Alebion, whom they fight and defeat—Alebion (Ἀλεβίων), in some sources called Albion (Ἀλβίων), being himself the son of Poseidon, the Sea God. After defeating his offspring Brutus renames the islands after himself, Britain. Oswald’s ballad begins:

It happened when oak trees were men when water was still water. There was a man, Trojan born, a footpad, a fighter. [30]

This is Brutus, who receives a vision from ‘the goddess’: ‘take aim, take heart,/Trojans, you’ve got to sail/til the sea meets the Dart’. So Brutus and ‘his gang’ set off.

A hundred down and outs the sea uninterestedly threw from one hand to the other, where to wash this numbness to?An island of undisturbed woods rises in the waves, a great spire of birdsong out of a nave of leaves. [31]

A holy place, then: a natural cathedral. The ballad ends, on p.33, with the approach of the giants, but the narrative stops before their defeat.

At Totnes, limping and swaying, they set foot on the land. There’s a giant walking towards them a flat stone in each hand.

The stones are presumably weapons—crude ones, and destined to fail before the Trojan swords, spears and shields—but the ballad-story doesn’t go any further, because the ‘flat stones’ link to the next of her interviewees, a builder of dry-stone walls. This figure, who gives us a page and a half excursus on the technique of wall construction, is a kind of avatar of Oswald herself, a poet with a ‘dry-stone style’, or such is the argument advanced by critic Jack Thacker

Oswald's poem is made up of the voices of those ‘who live and work on the Dart’ and among them is the ‘stonewaller’: ‘I can read them, volcanic, sedimentary, red sandstone, they all nest in the Dart … I'm a gatherer, an amateur, a scavenger, a comber, my whole style's a stone wall’. Oswald's stonewaller resembles Claude Lévi-Strauss's ‘bricoleur’, an individual who makes do ‘with “whatever is at hand”, that is to say with a set of tools and materials which is always finite'’. In writing Dart, Oswald exhibits a stone-wall style herself [in] the poem's interlocking poetry and prose … Echoing how a stonewaller constructs forms by ‘just wedging together what happens to be lying about at the time’, Oswald used interviews with the inhabitants of the Dart valley as the raw materials for the poem, creating an acoustic bricolage by ‘linking their voices into a sound-map of the river’. [Jack Thacker, ‘The Thing in the Gap-Stone Style: Alice Oswald's Acoustic Arrangements’, The Cambridge Quarterly, 44:2 (June 2015), 105]

This perhaps overstates the extent to which bricolage, as opposed to neo-Modernist formal technique, and skilful and vivid creative writing, constitute Oswald’s praxis—the interviews are ‘found-text’ repurposed, yes: but the rest of the poem is original writing, out of Oswald’s observations and imagination. And ‘dry’ is hardly le mot juste for a poem like Dart, which is profoundly, and in a good sense, wet. I can see what Thacker is arguing, but perhaps it relates more to Oswald’s other works. Dart is not about the seamless fitting together of units; it is not about walls or limits or containment. It is a poem that is, as per its antepenultimate line, ‘slip-shape’: it is protean, flowing, floody.

After the drystonewallman, the poem moves down to the harbour at Totnes, and the Dart finally reaches the sea. There are three pages of boat-names, some evocative, some mundane: ‘Oceanides, Atlanta, Proserpina, Minerva/ … Lizzie of Lymington, Doris of Dit’sum’ [34]. Some of the boat-poetry here baffled me, if I’m honest: ‘two sailing boats, like prayers towing their wooden tongues’. What does this mean? Are the wooden tongues rudders, or a small boat on a line dragged along behind? How are these boats like prayers? How is it that prayers have wooden tongues? ‘The rich man bouncing his powerboat like a gym-shoe’ is a little easier to parse, though I don’t know if gym-shoes are especially noted for tapping up and down, like a drummer’s foot. But the particularities of a British seaside town are well evoked:

under the arch where Mick luvs Trudi and Jud’s heart has the arrow locked through itsix corn-blue dinghies banging together Liberty Belle, Easily Led, Valentine, L’Amour, White Rose and Fanny …in the shine of a coming storm when the kiosk is closed and gulls line up and gawp on the little low wallthere goes a line of leaves [35]

I like the double-entendre names of the dinghies, the sexualised ‘banging together’ picking up the ‘luv’ graffiti under the arch. The poem gives us an amateur boat-builder, looking forward to retirement when he and his wife will take the boat he is constructing (‘every roll of fibre glass two hundred quid’) and go to the Med, where he and his wife can spend their time ‘soaking up the sun’. Then the longest of the pieces of testimony, a ‘salmon netsman and poacher’ who goes on for many pages (37-43) about his business, illegally netting the fish, or out in the bay, fighting with the other poachers and wrecking their rival nets. Then the man who runs the car ferry; then a ‘rememberer’, at first unspecified, flowing into the memories of ‘former pilots on the Dart’

The cod fleet and the coal hulks and the bunkers from the Tyne and A man sitting straight-up, reading a book in the bows while his ship was sinking [46]

Then for the last page the voice shifts back to that of the Dart itself. The river notes these fishermen and pilots (‘they start the boat, they climb/as if over the river’s vertebrae/out of its body into the wings of the sea’ [47]—wings like a bird? Wings as in the sides of a stage, or a stately home? I’m not sure.) Then there some ‘I’ verses, the river speaking in propria persona:

I steer my wave-ski into caves horrible to enter alone …At low water I swim up a dog-leg bend into the cliff, the tide slooshes me almost to the roofand float inwards into the trembling sphere of one freshwater drip drip drip where my name disappears and the sea slides in to replace it [48]

The Dart becomes nameless. It is in this chamber, this sea-cave, that the poem ends, accompanied by some seals and another god.

twenty seals in this room behind the sea, all swaddled and tucked in fat, like the soul in its cylinder of flesh.With their grandmother mouths, with their dog-soft eyes, asking who’s this moving in the dark? Me. This is me, anonymous, water’s soliloquy,all names, all voices, Slip-Shape, this is Proteus, whoever that is, the shepherd of the seals, driving my many selves from cave to cave …

‘Slip-shape’ morphs ship-shape into a more flowing, appropriate form. As for Proteus, he was in Greek mythology the prophetic god of rivers and seas—Πρωτεύς meaning ‘first’, perhaps because he was Poseidon’s first-born son (another Son of the Sea, like Albion, mentioned, or alluded to, earlier in Dart—‘albion’ means white, supposedly a reference to the white cliffs of Kent). Oswald, classically trained and in her other books a translator-adaptor, inter alia, of Homer, knows that The Odyssey calls Proteus ἅλιος γέρων, the prophetic old man of the sea. He is a shape-shifter—hence our word protean—like Oswald’s ‘slipshape’ river, and it is Homer who styles him the shepherd of seals. This is from Odyssey 4, in which Telemachus, looking for his father, travels to Sparta and speaks with Menelaus and Helen, now reconciled after all the pother of the Trojan war. They have info: and tell Menelaus about their return from Troy, which was a lot simpler than Odysseus’s proves: they voyaged by way of Egypt where, on the island of Pharos, Menelaus met the sea-god Proteus, who told him that Odysseus was a captive of the nymph Calypso. Pharos is a day’s sail from Egypt, and to begin with Menelaus and his crew are stuck there:

There for twenty days the gods kept me there, nor did the winds that blow over the deep, the winds that speed men's ships over the broad back of the sea, ever once spring up. And now would all my stores have been consumed and the strength of my men, had not one of the gods taken pity on me and saved me: this was Eidothea, daughter of mighty Proteus, the old man of the sea; for her heart above all others had I moved. She met me as I wandered alone apart from my comrades, who were roaming ceaselessly about the island, fishing with bent hooks, to assuage the hunger that pinched their bellies. [Odyssey, 4:361-9]

The name of Proteus’s daughter, Eidothea, Εἰδοθέη, means ‘image of god’ or ‘vision of god’. The name ‘Oswald’ is from the Old English Osweald, ōs (“god”) + weald (“power”). Strength of God; Vision of God). The seals, on which Dart ends, are her children. Menelaus says that, in the day, Proteus lies down to sleep ‘in the hollow cave’, and:

ἀμφὶ δέ μιν φῶκαι νέποδες καλῆς ἁλοσύδνης ἁθρόαι εὕδουσιν, πολιῆς ἁλὸς ἐξαναδῦσαι, πικρὸν ἀποπνείουσαι ἁλὸς πολυβενθέος ὀδμήν. [Odyssey 4:404-6]… and around him the seals, the young ones of the fair daughter of the sea, sleep in a herd, coming forth from the grey-haired water, and bitter is the smell they breathe out of the depths of the sea.

The seals, φῶκαι (fōkai) are the νέποδες, the ‘children’, of Eidothea. According to Hesiod, Proteus married one of his sea maidens, Psamathe, daughter of Nereus, who gave birth to ‘Phocus’, that is ‘seal man’ [Hesiod, Theogony I003-5]. In a related myth, recorded by Apollodorus, Psamathe was pursued by Aeacus, king of Aegina, and changed herself into a seal (Φῶκος) to escape his attentions of Aeacus—although this stratagem didn’t work, and she bore Aeacus a son, Phocus.

Oswald describes seals as ‘all swaddled/and tucked in fat, like the soul in its cylinder of flesh’, which is strikingly put. But the salient is surely that, like Proteus, seals are believed to be shape-shifters:

The seal holds a peculiar place in European folk tradition. We learn that at certain times seals may change their appearance and take on human shape. Generally this is managed by laying aside their skins, whereupon they appear often as beautiful mermaids. If the temporarily discarded skin is taken, the mermaid to whom it belongs follows the taker and appears to be in his power. A great number of folk tales revolve about the situation in which a fisherman, possessed of such a skin, forms a union with its owner, who has children by him and remains on land as his faithful wife, until some chance discovers to her hidden skin. She is thereby freed from captivity and with her long-lost cloak takes again to the sea. She may still haunt the locality showing a love for her children, who eventually may or not be drawn into a life under the sea. [Kevin O’Nolan, ‘The Proteus Legend’, Hermes, 88:2 (1960), 134]

The river changes shape multiple times in Oswald’s poems, thronging with the dead and the drowned, and arrives at the sea and Proteus and the strong-god-vision woman’s words.

Rivers. The spring from which Dart, and other poems of the same form, rise, is Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922)—also a river poem, of course, although this is perhaps a fact that is not always forgrounded in readings of the work. The river in Eliot’s case is the Thames, and in its carefully splintered and agitated form the poem returns to its flow, from crossing London Bridge in part 1, to the intimations of drowning in part 2 (the tempestuous ‘those are pearls that were his eyes’) to the ‘broken tent of the river’ in 3 (‘The Fire Sermon’):

the last fingers of leaf Clutch and sink into the wet bank. The wind Crosses the brown land, unheard. The nymphs are departed. Sweet Thames, run softly, till I end my song. The river bears no empty bottles, sandwich papers, Silk handkerchiefs, cardboard boxes, cigarette ends Or other testimony of summer nights. The nymphs are departed. And their friends, the loitering heirs of city directors; Departed, have left no addresses. By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept . . . Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song, Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long.

‘Sweet Thames …’ is Spencer’s Epithalamium, a sweet marriage song, ironically invoked for this rubbish-filled 20th-century river, where Frazer’s Fisher King sits fishing (in ‘the dull canal behind the gashouse’). One of The Waste Land’s many speakers says ‘This music crept by me upon the waters’ (Tempestuous, again), but the ‘here’ is ‘a public bar in Lower Thames Street’,

The river sweats Oil and tar The barges drift With the turning tide Red sails Wide To leeward, swing on the heavy spar. The barges wash Drifting logs Down Greenwich reach Past the Isle of Dogs. Weialala leia Wallala leialalaElizabeth and Leicester Beating oars The stern was formed A gilded shell Red and gold The brisk swell Rippled both shores Southwest wind Carried down stream The peal of bells White towers Weialala leia Wallala leialala

This contrast between an industrialised, degraded present (those barges) and the idealised courtly beauty of the past, Elizabeth passing along the river in a red-and-gold boat, is both clumsy and dubious: Oswald does not idealise or fetishize a notional past in her poem—Dart is not so gloomy or sour a poem as The Wate Land. But she does see the present as interpenetrated with the mythological, as does Eliot. The ‘Weialala leia/Wallala leialala’ is what Wagner’s Rhinemaidens sing at the beginning of Das Rheingold, another very important river poem, or river music-poem. This opera opens accompaniment of that a sustained e-flat drone, together with a series of upreaching and downfalling arpeggios, musical correlatives to the flow of the river—until the semi-divine Rhinemaidens cut in with their weia and walla and weiawalla-ing.

Reviewing the first Bayreuth performance of The Rhinegold in 1876, the Viennese critic Daniel Spitzer commented as follows on the opening moments of Scene One: ‘One of the Rhine-daughters, Woglinde, swims to the surface and, with a delightful wriggling movement, circles around a rocky ledge in the centre of the stage, while at the same time emitting a series of natural sounds, “Weia! Waga! Wagalaweia! Wallala weiala weia!”; these sounds have been devised by the Master himself and have achieved great notoriety, but since they have never before been put to use, we are uncertain what frame of mind they are in fact intended to express. The cry of “Weia!” seems to indicate a very disagreeable sensation, the call of “Wallala!”, on the other hand, a particularly agreeable one, so that the two together may be intended to characterise the feeling of alternating pleasure and displeasure experienced on immersing oneself in a cold bath.’ [Stewart Spencer, ‘The Language and Sources of The Ring’, in Nicholas John (ed), The Rhinegold/Das Rheingold (New York: Riverrun Press 1985), 31]

This strange refrain was so controversial, and so widely mocked, on the opera’s first performance, that Wagner wrote an open letter to Nietzsche in 1872 justifying himself.

From my studies of J. Grimm I once borrowed an Old German word Heilawac and, in order to make it more adaptable to my own purposes, reformed it as Weiawaga (a form which we may still recognise today in the word Weihwasser [holy water]; from this I passed to the cognate linguistic roots ‘wogen’ [to surge] and ‘wiegen’ [to rock], finally to ‘wellen’ [to billow] and ‘wallen’ [to seethe], and in this way I constructed a radically syllabic melody for my watermaidens to sing, on an analogy with the ‘Eia popeia’ [hushabye] of our children’s nursery songs.

I like to think this section of The Waste Land, ‘The river sweats/Oil and tar…’ and so on, is to be read slowly, in low tones, to the accompaniment of that music. Wagner chooses these unusual, vocalic approximant words to signify holy surging water, billowing and seething, and they capture almost onomatopoeically. His river is the Rhine, on of two great Germanic rivers, flowing north. The other is the Danube, flowing south.

Friedrich Hölderlin’s ‘Der Ister’ (the title refers to an ancient name for the lower stretch of the Danube) opens with a ‘now’ (‘Jetz komme, Feuer!’ now come, fire!) and a ‘here’ (‘Hier aber wollen wir bauen’, Here, though, we will build or here we will settle). Heidegger, in a celebrated essay on the poem, notes that ‘what is proper to the river is the fact that it flows and thus continually determines another “here” … rivers designate a “Here” and abandon the Now, whether by passing into what is bygone or into what lies in the future.’ [Martin Heidegger, Hölderlin's Hymn ‘The Ister’ ([1942], translated by William McNeill and Julia Davis; Indiana University Press 1996), 15]. For Hölderlin the Ister is also its mythic antecedents: the Greek name for a modern river. ‘The Ister’ opens with an invocation of other rivers: the Indus, a sacred river in the East, and the Greek mythological river Alph, in the west.

But we come singing from the Indus

And the Alphaios afar, having

Searched long for that which

Is befitting. No one can grasp

Straight at what's closest

Without wings, and then

Arrive at the other side.

Here is where we’ll settle.

E S Shaffer notes the similarities between Coleridge and Hölderlin: born around the same time, both Nature poets, both transmuting Enlightenment thought into Romanticism—‘both men, concerned with old forms, the epic, the Greek ode, founded new forms and made metrical departures’. Coleridge’s Alpheus is removed from Greece and relocated to China as ‘Alph the Sacred river’. Ted Hughes (him again) argued that naming this flower ‘Alph’ was Coleridge’ inscribing it as language, the holy alphabet, the letters that pass through the subconscious and burst out into the conscious mind, the inspired poet-figure at the end of ‘Kubla Khan’ reflexively producing the poem (‘that sunny dome! those caves of ice!’):

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread:

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drank the milk of Paradise.

If Dart remakes Coleridge’s The Brook for the 21st-century, adding marginal glosses like The Ancient Mariner, it also re-flows the course of the Alph, the sacred river passing underground and overground—bursting out, sinking down, flowing. The Coleridgean river is the stream of words, Alphabet the Sacred, as Hughes suggests: ‘the river of ultimate love and of the ultimate Word’, just as ‘Mount Abora’ in the second half of the poem is, Hughes insists, ‘A + B (=Alphabet) + ora “pray” … Coleridge is saying “O Mountain of Alphabet pray for us”’.

On Prosody. The figure identified in this first line, ‘the walker’, says: ‘what I love is one foot after another’, which is also what characterises a poem. Walking the path of the river. Putting together metrical feet in the creation of a poem. So far as prosody (and form) are concerned, Oswald is suspicious of too much regularity. She likes a rougher stitch, adding extra-syllabic moments, mixing rhymes and half-rhymes. Here’s a short lyric inserted near the end of Dart:

the day the ship went down and five policemen made a circle round the sand and something half imagined was born in blankets up the beachall that day a dog was running backwards forwards, shaking the water's feathers from its fur and down the sea-front noone came for chipsand then the sun went out and almost madly the Salvation Army's two strong women raised and tapped their softest tambourines and someonestared at the sea between his shoes and I who had the next door grave undressed without a word and lay in darkness thinking of the sea

The sense here is clear enough: a boat has sunk and some of its crew have (or perhaps only one person has) drowned; the authorities have covered a dead body under a blanket on the beach; a dog runs to and fro, getting wet and shaking itself dry; the area has, perhaps, been cordoned off because of the disaster (so the usual beachgoers and tourists aren’t buying chips); at sunset two Salvation Army women go past. The final stanza here is less clear: perhaps the speaker of these quatrains is in a seafront hotel, watching events from his hotel window—the person occupying the next-door room is sitting on his balcony with his feet up, looking between then; the speaker goes into his room (styled, in gloomy mood, a grave) and goes to bed, but does not sleep. He lies in darkness and thinks about the tragedy. But prosodically this is interesting: a set of iambic tetrameters, with a scattering of internal half-rhymes (down/round; forward/water’s; madly/Army; grave/lay; undressed/darkness)—but where many of the lines here are regularly, even insistently iambic—de-DUM de-DUM de-DUM de-DUM (the DAY the SHIP went DOWN and FIVE/poLICEmen MADE a CIRcle ROUND)—others slip-in extrametrical syllables (the ‘was’ in ‘imagined was born’; the the in ‘shaking the water's’; the ‘that’ in ‘all that day’, ‘at the’ in ‘stared at the sea’). It’s just enough to throw a roughness into the mix, to distress the prosodic texture.

But then the prosody of Dart is a fascinating, complicated thing. Much of the verse (and a good portion of the prose) rides on the iamb, that workhorse of English poetry, the which Oswald varies with trochees for variety, and some spondees for emphasis. But that’s not all. Look at the very first line of the poem:

Who’s this moving alive over the moor?

That’s is an abbreviated choriambic line. Indeed, if we want to add-on the first line of the marginalia (‘the source’) it’s a complete line of what is called, technically, a minor Asclepiad.

To dilate on this a little: a choriamb is a metrical foot that welds a trochee (choreus is another word for trochee) to an iamb. So: each choriambic foot is: long-short-short-long, or in terms of ictus, stressed-unstressed-unstressed-stressed: ( — ‿ ‿ — ). Choriambs crop up all over the place — for instance, in the naming of famous duos: Morecambe and Wise, Watson and Crick, Oryx and Crake, Starsky and Hutch. Put together into a metrical line the effect, in English, can be of a rocking back-and-forth: foolish Ramón, laughed at the troll, under the bridge, what a mistake. Or it can be subtler, more fluent, as in Swinburne’s 1878 poem ‘Choriambics’, with its exquisite balance of long-short pulses and stressed-unstressed syllables, of a sighing, or sobbing:

Lóve, whát áiled thee to leáve lífe that was máde lóvely, we thóught, with lóve?

What sweet visions of sleep lured thee away, down from the light above?What strange faces of dreams, voices that called, hands that were raised to wave,

Lured or led thee, alas, out of the sun, down to the sunless grave?

This poem goes on, and it’s beautiful, but stop here for a moment. Swinburne’s poem is not made solely of choriambs: each line opens with a spondee — two stressed syllables — and each ends with an iamb.

This is a specific verse form, technically known as ‘Asclepiadean’, after the obscure third-century BC Greek poet Asclepiades of Samos, who wrought three different kinds of verse comprising lines of bracketed choriambs:

Swinburne’s poem is in the third of these metres, of course. We could say that Oswald’s opening line to Dart is a minor Asclepiadean

Swinburne, in his poem, is copying Horace, three of whose Odes are composed to this rhythm (1.11, 1.18 and 4.10). Actually Horace very often writes choriambic verse: thirty-four of his odes are in various Asclepiadean metres. But the specific pattern of the fifth Asclepiadean, which Swinburne has copied in his poem, is associated particularly with 1.11, the poem from which we get the tag carpe diem: ‘seize the day’. That poem opens (you can see it in the metrical itinerary, above) Tu ne quaesieris, scire nefas, quem mihi, quem tibi.

The step-step, swinging throughline of an Asclepiadean is distinctive: DUM/DUM//DUM-duh-duh-DUM//DUM-duh-duh-DUM// DUM-duh-duh-DUM//duh-DUM. Swinburne’s poem reinforces this prosody by compartmentalising phrases into the metrical units:

[Love] [What] [Ailed thee to leave] [Life that was made] [Lovely we thought] [with love?]

[Lovst] [Thou] [Death is his face] [Fairer than love’s] [Brighter to look] [upon]

I say more about Swinburne’s poem (and Horace) here. But to go back to Dart.

[Who’s] [This] [Moving alive] [Over the moor] [the source]

Choriambs are not the dominant metrical foot in Oswald’s poem, but there are quite lot of them nonetheless, and many ‘spondee choriamb’ combos, like the beginning of an Asclepiadean line. Oswald is a trained and expert classicist: it seems to me impossible that she doesn’t know about this Horatian metre. So at the bottom of p.1 we have:

[secret] [buried in reeds] [won’t let] [go of a man] [under] [soakaway ears] [but there’s] [roots growing round]

all within a few lines of one another, and on p.2 (after this Minor Asclepiad: ‘I go, slipping between, into a bowl, of moor’) a little cluster of choriambs stacked together:

linked stones trills in the stones glides in the trills eels in the glides in each

—which is a Major Asclepiad; and on p.3 another Minor Asclepiad:

He sits, clasping his knees, holding his face, low down

And on we go. A complete itinerary of all the choriambs, and all the Asclepiads, in the book would grow wearisome, but you get the idea. This meandering around prosody—mine, I mean—is an attempt to get a handle on the rhythm, the pulses and flows, of Oswald’s long piece. Ezra Pound’s famously rejected what he called ‘the yakkety-yakkety-yak of iambic pentameter’, and at the same time endorsed the poetic power of the image above all. Oswald is not so allergic to the yakkety-yak, although not so clockwork as to scaffold her whole poem upon it; and although Dart scintillates with many vivid and memorable images, vividly and memorably phrased in English, the poem is not imagist.

The Drowned. I wanted to move on from this prosodic digression to talk about the drowned, via Sean O’Brien’s 2007 collection The Drowned Book, a book of poems about water, rivers and, yes, the drowned.

There are various drowned people in Dart. But rather than getting to that, I find myself dallying further with metre. Consider this an awkward segue, me refusing to let go of the prosody baton. Because reading O’Brien’s various poems, three-stress and four-stress lines, free-verse-adjacent, I was struck by how often his phrasing defaults to dactyls. Nothing so regular as fully dactylic verse, but the coming together of multiple dactyls in the midst of other rhythms and metres. As it might be—just taking examples from the first ten pages, dactyls runnings smoothly to that end-stopping of the Homeric hexameter, a trochee or spondee: ‘leaning and listening/There on the steps of the cellar’ [4]; ‘patient amphibian angels’ [5]; ‘Estaurine polyps and leathery … no one has thought of a name for // … river revisits his cellar/caressing’ [6]; ‘[The] Ferry The Waverley Churns on the sandbar // … Leaving us wormcasts and Biblical distance/With skeleton crews’ [10]; ‘Sites of municipal vaticination’ —none of the poems from which these lines are quoted are in themselves written in dactyls, and yet here we are. One poem has a dactylic title: ‘Eating the Salmon of Knowledge from Tin [Cans]’. The Drowned Book contains one prose poem, ‘The River in Prose’, and even here the dactyls come bubbling up: ‘Riverman pubs where the river is penned in the cellars’—a perfect dactylic hexameter, worthy of Homer.

It strikes me, I think, because Oswald is not fond of dactyls, and doesn’t much bring them into her verse. It’s a trotting or galloping sort of rhythm, famously used for poems of motion, horse-action, a military charge (the Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold, And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold), or Browning’s galloping race to bring the good news from Aix to Ghent (I sprang to the stirrup, and Joris, and He;/I galloped, Dirck galloped, we galloped all Three …) But O’Brien’s is a book about water, about flow—river flow, tidal flow—about flooding, and rivermen, and swimmers, and, as its title makes plain, about the drowned. Is the flow of a river dactylic? I’m not sure it is. Oswald’s choriambs, tumbling on then pulling back, are there (I suppose) to replicate the complex cross-currents of the main flow, especially in the early portions of Dart, when the river is gushing out into the moor, running into pools, cascading down rocks and so on. As Oswald’s poem continues its choriambs settle, and a steadier essentially iambic and spondaic set of rhythms come to predominate. Do dactyls capture the passage of water as well? Here, from early in O’Brien’s collection, is one of the poems from which I pulled out some dactyls (above): ‘Water Gardens’, a poem about a waterlogged and flooded lawn.

Water looked up through the lawn Like a half-buried mirror Left out by the people before.There were faces in there We had seen in the hallways Of octogenarian specialists,Mortality-vendors consulted On bronchial matters In rot-smelling Boulevard mansions.We stood on their lino And breathed, and below us The dark, peopled waterWas leaning and listening. There on the steps of the cellar Black-clad VictoriansWere feeding the river with souls. [O’Brien, The Drowned Book (2007), 4]

We are, perhaps, in a hospital or clinic, and we have gone there to have our bronchial unhealth examined. The facility doesn’t sound entirely salutary, because, presumably, the infrastructure is old, a barely modernised Victorian structure: rot-smelling rooms, lino on the floor, portraits of long dead doctors on the walls. What has presumably been an extended period of rain has flooded the garden and the speaker of the poem looks into this half-mirror and sees the afterlife, the underworld, the river that flows below and through all things and carries away our souls. The Drowned Book is dedicated to O’Brien’s mother, who died the year the book came out, so conceivably this poem records a visit undertaken on her behalf. The nineteenth-century building is still populated by ‘mortality vendors’, ‘feeling the river with souls’. Death is burial in the earth, but in O’Brien’s Dantean reimagining it is also a drowning, an immersion. Here the hospital lawn is flooded, but so is the town cemetery:

Their miles of flooded graves Were traffic jams of stone Where patient, amphibian angels Rode them under, slowly.

Beautifully phrased. We bury the dead, when we don’t cremate them: but in O’Brien’s waterlogged ground, this is tantamount to drowning them. And

There is something deeply eerie about the drowned dead looking up at us through the water. In Lord of the Rings, Gollum leads Frodo and Sam through ‘the Dead Marshes’, with Gollum explaining the origin of the territory, and the reason why so many dead are visible beneath the water—they were slain and drowned in the Battle of Dagorlad, fought at the end of the Second Age: an alliance of the Elves of Gil-galad and the Men of Elendil fighting Sauron and the forces of Mordor. Gollum calls it as ‘a great battle’, fought ‘before the Precious came’: ‘Tall Men with long swords, and terrible Elves, and Orcses shrieking. They fought on the plain for days and months at the Black Gates. But the marshes have grown since then, swallowed up the graves; always creeping, creeping.’ In the Peter Jackson movies this battle was where Isildur cut the ring from Sauron’s hand, although in Tolkien’s legendarium that happened later: after his defeat at Dagorlad Sauron retreated to Barad-Dur, which was besieged for seven years, and afterwards he was killed on the slopes of Mount Doom—which is, his mortal form, though he of course continued living—and Isildur cut the ring from his dead hand.

This all happened thousands of years before Frodo and Sam’s passage through the marshes, so the fact that the dead of Dagorlad were still present, not rotted away to nothing, speaks to malign magic, or some supernatural force. They are dead but not entirely dead, and siren-like they exert a pull—Sam looks with horror at the rotting faces illuminated by spectral candles that look up at him, but Frodo, on the other hand, stares with morbid fascination,; and reaches out, until Sam snaps him out of his trance. (In the movies Frodo falls into the water, and the drowned corpses come to hideous life and motion until Sam hauls him out again). The uncanny drowned. Section 4 of The Waste Land is ‘Death by Water’:

Phlebas the Phoenician, a fortnight dead, Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep sea swell And the profit and loss. A current under sea Picked his bones in whispers. As he rose and fell He passed the stages of his age and youth Entering the whirlpool. Gentile or Jew O you who turn the wheel and look to windward, Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.

Eliot’s dead Phoenician is Jew not Gentile—is, it has to be said, an engagement with Eliot’s anti-Semitism, and the anti-Semitism of his age (I talk about this here). Oswald’s poem is not anti-Semitism, or indeed interested in Jewishness at all, but something of the eerie quality of this plangent section of Eliot’s poem informs her own writing: the swell of the water, the fluid dismantling of bodies and bones. This is the shortest of The Waste Land’s five sections, and the most epiphanic. It holds, amongst the the dried and desert lands of the first three sections, and the droughtscape of (the opening portion of) Part 5 (‘here is no water but only rock/Rock and no water and the sandy road/The road winding above among the mountains Which are mountains of rock without water … Dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit’), its bulb of water, its Frazerian sacrifice, the lamed-king dying so that the king can be reborn, ready for the final section of Part 5, when the rain comes, the drought ends, rebirth begins and we achieve that Shantihean peace-that-passeth-all-understanding (we could say, given the Arthurian elements in Eliot’s work, it is a Tristram Shantih).

Various people are identified as drowned in Oswald’s Dart, but not all of them are given voices. Of those that are, there is Jan Coo; then the canoeist (p.13’s marginalium: ‘near Newbridge, a canoeist drowned’)—this individual is unnamed in the poem, but it would take a stronger will than mine to resist the urge to call him ‘Jan Canoe’—and then ‘John Edmunds, who was washed away and drowned at Staverton Ford in 1840’, and whose death occasions the two silent, that is blank, half-pages on p22 and p23. Before that Edmunds speaks from under the water:

All day my voice is being washed away out of a lapse in my throat [20]

Lapse in the sense of failure, a falling away, a pause in continuity; but also playing with the homophone, for water ‘laps’. There are other drowned people, some named and some not (the medieval knights-in-armour, ‘poor Katy Pelham and the scout from Deadman’s pool’ [24], three oystercatchers [39] and the nameless corpse on the beach, under a blanket [45]) but only these three speak, their voices their own and the voices of the river itself, ‘lapping’ via their throat. When, later, an oystercatcher and fisherman recalls catching a seal in his net: ‘I thought it was a corpse once when I had a seal in the net—huge—sealion’ [40]. This looks forward, I think, to the last stanzas of the poem, Proteus and his group of seals, drowned men reborn. In the Eastern Mediterranean and East Europe there is a tradition, as Kevin O’Nolan, cited above says, ‘a widespread belief associating seals with the disaster suffered by Pharoah and his army when pursuing the Israelites across the Red Sea. According to this tradition, when the sea engulfed the pursuers, they were not drowned but changed into seals. The hoarse cry of the seal—‘farao’—is said to be the name of their old master, the ruler of Egypt, on whom they still call.’

Of Jan Canoeist, the poem has the river hush him, after (we intuit) his noisy death: ‘will you rustle quietly and listen to what I have to say now … will you unsilt[?]’ [15]. This last suggests that the drowned man is a kind of filter, that his perception, his posthumous listening and speaking will in some way purify the river’s flow. What is it the river ;has to say now’? It is

describing the wetbacks of stones golden-mouthed and making no headway

I was going to ask whether it is the stones, or the speaking river, that is golden-mouthed (Χρυσόστομος , the Greek for ‘golden-mouthed’, is a nomination applied to a number of Early Christian preachers celebrated for their eloquence, most famously the 4th-century Constantinople Archbishop John Chrysostom)—but then I figured: it’s both. The stones are in the way of the water, which flows over and around it, and in its sunlit shine opens stomata-like eddies and spaces, as if the stones are opening their mouths, although it is the water. The river is golden-mouthed because the river is eloquent, Dart is the Alph-the-sacred river-of-language. Dart is not wholly confident in its articulacy, though; or perhaps we should say, not confident in its ability to speak the language of humanity.

This jabber of pidgin-river drilling these rhythmic cells and trails of scales, will you translate for me blunt blink glint [15]

The river blunts sharpness—despite its sharp-sounding name—with the rub of its flow; the river blinks and glints in the light. Step back to Jan Coo, who is under the water and thinking about leaving.

Oh I’m slow and sick, I’m trying to talk myself round to leaving this place but there’s roots growing round my mouth, my foot’s in a rusted tin. One night I will. [4]

I don’t think we believe him.

Ecopoetics. That ‘rusted tin’ is interesting. For an eco-poem—if that’s what Dart is—there is surprisingly little attention paid to human pollution. There’s this tin-can, there’s some old discarded knitwear (the fisherman recalls ‘I hooked an arm once, petrified, slowly pulling a body up, it was only a cardigan’ [8]), the impurities removed by the water abstractor (‘magnatite … black inert matter [25]) and an old sack mentioned in passing [28]. But that’s all. For comparison, organic matter, natural stuff, twigs and leaves and moss, ‘the fur, the hair, the fingernails, the bones’, are all through this poem. It’s not that the Dart is crystal clear flow: its turbid, muddy, sometimes ‘nectarine, nacreous … orange’ [23] with particulates. But it’s not, it seems, over-polluted by humanity. Perhaps the Dart is unusually clear of such waste, though this seems unlikely to me. I think of the scene in Spirited Away where a ghastly, reeking stench-monster, the ‘stink spirit’, a blob of black and brown slime and horribleness, comes to the bath-house, and Sen cleans it—with heroic effort—retrieving from its body all manner of human rubbish and pollution, old bicycles and shopping trolleys and bits of cars, tangles of pipes and plastic, trash and rubbish. Finally it the true river spirit emerges in a gush of clean water: an old Noh mask on the front of a serpentine dragon of river. But there’s nothing like this in Oswald’s poem.

Oswald’s poem is, if you’ll excuse the pun (you won’t excuse it: why would you?) a verbal Objet d’Art: a carefully crafted, worked and finished piece, a ‘well wrought urn’. Indeed, Oswald’s skill and craft are so fine that the poem runs the risk of becoming too polished, to refined and ‘crafted’. It seems strange to object to Oswald’s ‘craft’, her verbal skill, her ability to turn a striking and memorable phrase, but she herself clearly works her finished poem to introduce roughnesses, to distress its textures and balances. I remember reading an interview with Graham Coxon, in which he talked about his role in Blur’s songwriting. He said (I quote from memory) ‘Damon comes to us with all these pretty pieces of songwriting, and my job, as we record them, is to fuck them up a little bit’. And in another sense the ‘Objet d’Art’ pun mischaracterises Dart, which is not an object (except in the literal sense that it is a book)—which works much more subjectively than objectively. The river speaks through the whole poem, and everything—I think—is observed, framed, through what we might call its ‘subjectivity’. Perhaps that’s why there’s so little emphasis on human pollution in the poem: not that humans aren’t polluting the natural world, but that from the river’s perspective this is a small matter, trivial passing. Where eco-lit often essays a critique, or satire, of the depredations of the Anthropocene, Oswald’s poem is doing something else: giving voice to the riverine era, the Fluocene. Or perhaps ‘Potamocene’.

I do think its hard to bracket Oswald as an ‘eco-poet’, however engaged she is with the natural world, however much joy and beauty she finds in nature, however much she cultivates her garden, poetically speaking. Environmentalism is about conservation, a past-oriented and conservative, in a non-party-political sense of the word. Dart is a poem about continual change and onward movement, a Thom-Gunn-esque ‘man you got to go’ onwardness. I think Robert Baker is right: ‘“Change alone is unchanging”, Heraclitus says. Oswald is a Heraclitean poet. Metamorphosis and mimesis are among her primary themes’ [Robert Baker, ‘“All voices should be read as the river's mutterings”: The Poetry of Alice Oswald’, The Cambridge Quarterly, 46:2 (2017), 99-118; 103]. Insofar as pollution is the clogging and obstruction of flow and change, Dart is not interested in it. It is a poem of renewal: myth renewing itself as history, history renewing itself as the everyday experience of people’s lives; rain renewing itself as fertilising river, the land renewing itself through the seasons. This renewal is not just flow, it is a kind of emptying. Baker again: ‘there is in Oswald, I think, a pliant lyrical version of what the Christian tradition calls mystical kenosis. A certain emptying of the self is a part of a crossing into other regions of life.’ [Baker, 106] This connects her with Coleridge (again) in that she finds the sacred in the ordinary, sanctity in the voiding flow of the river, its destination the slip-shape Protean divine principle. Coleridge’s Alph is a sacred river in a deep way (deep in more than one sense of the word); his Ancient Mariner empties himself, or is emptied, by his extraordinary experiences—we are not even left with his name—leaving him a vessel for nothing but the poetry that construed him, and which he is compelled to go about the countryside reciting to all and sundry. And in The Brook Coleridge planned a poem about everything, like Wordsworth’s The Recluse, containing ‘description, incident and impassioned reflections on men, nature, and society’. But the way to write about everything was to structure is along the path of a river that, by its nature, empties itself continually into itself and eventually into the sea. It is a kind of kenosis that reaches a strange sort of apotheosis in Coleridge’s career when he emptied the pages of words and wrote no poem at all.

This is a lovely piece, Adam, which you gravely fucked up a bit I hope. It brings to mind Richard Flanagan's long drowning sequence in Question 7, and Leo Szilard's long baths and his—their—tracing back to Wells the wellspring of fission in The World Set Free, at least as Szilard saw it. I've been reading Sebald's After Nature, thinking about nonhuman sentience, as I do, and one of your contentions struck me, that conservation is conservative and past looking. I don't know if this is so much untrue as cracking open for me what is an almost elemental struggle, since preservation is all about preserving the future and seeing the source of our survival in the past, a bit like taking advice on policy from historians. Perhaps it's that we look for clues to better progress in our own past and not in nature's. There is something in this which connects me to your remark about Oswald's lack of river rubbish (aside from corpses). Not sure where I'm going with this, but it's fascinating. Thanks!

I will have to print this to read it properly. Thank you for writing it. I have enjoyed Oswald’s work.