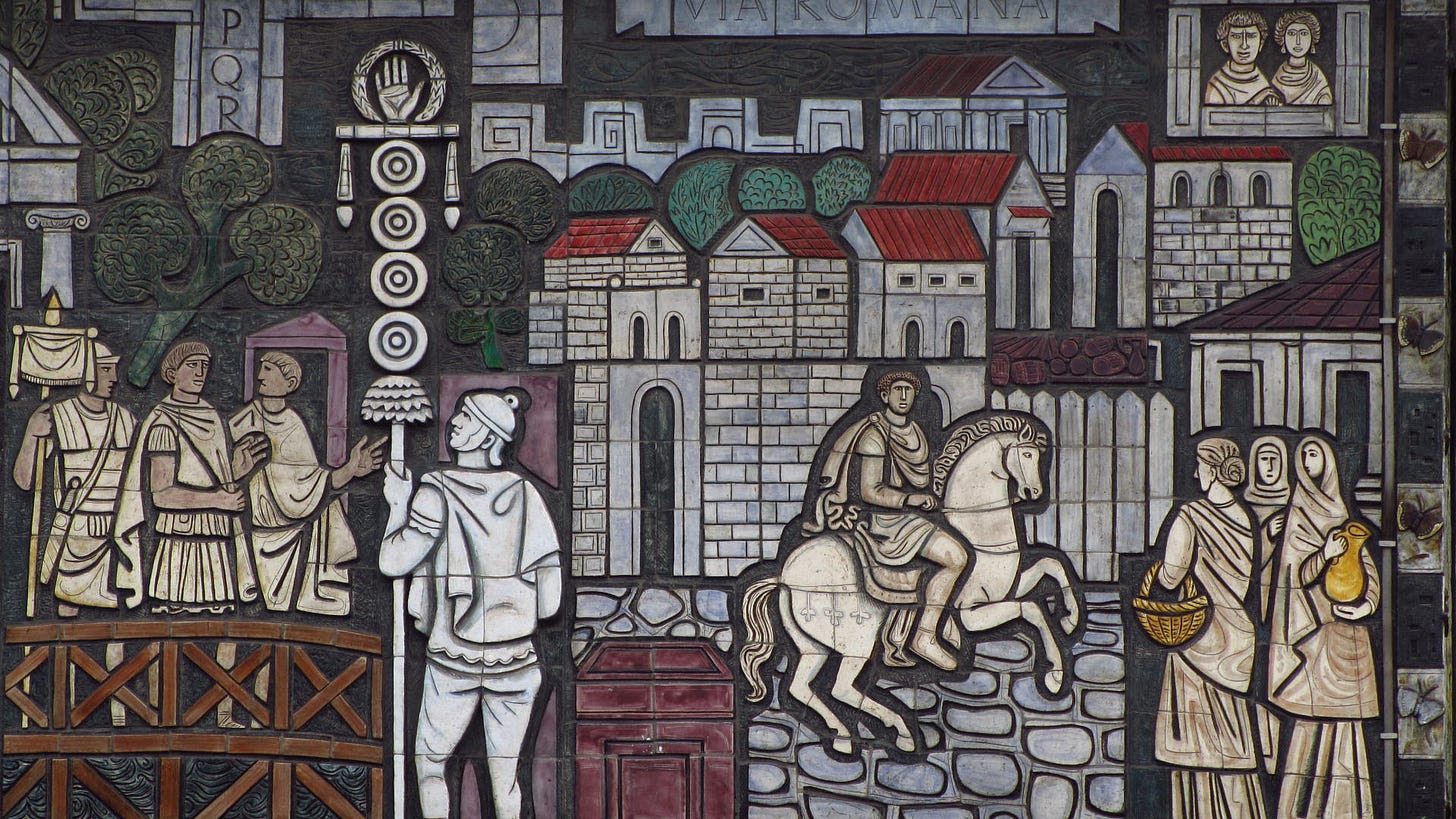

Adam Kossowski, ‘History of the Old Kent Road’ (1965)

A mural on the former North Peckham Civic Centre

A personal, though not especially pertinent, prelude: my parents were living in Peckham when I was born (in, coincidentally, 1965) though they moved away when I was three, first for a year to the USA, then to Sydenham SE23, and after that, when I was nine or so, to Canterbury in Kent—down, in a sense, the Old Kent Road out of London. So though I could technically claim to be an aboriginal Peckhamite I have never seen this mosaic mural in the flesh.

The Twentieth Century Society website says ‘at 1000 square feet this is the largest secular work of the sculptor Adam Kossowski’ (he made larger mosaic murals for a couple of churches, on religious themes). ‘The frieze, which depicts local historic scenes in high relief, was designed in 1964 and completed in 1965. Kossowski was Polish and is most noted for his works for the Catholic Church, including some very fine ceramic work in the chapel of St. Aloysius Roman Catholic Church, Phoenix Road, Camden.’ I may have to schedule a trip to see it in person: it’s gorgeous. The four walls are disposed into five consecutive (as, I presume, one walks around he building) scenarios. First: Roman Britain.

Kossowski’s Londinium has an almost stained-glass quality to it, with those thick black borders around the key figures isolating them from the stylised cityscape behind, and the elements of brighter colour (green trees, red roofs, the gold pitchers of the women) standing out against a glassy grey of stonework and road. The signifer in the foreground is larger than the eques on the paved road to his right, which makes it look as though Kossowski is going at least some way down towards representing perspective; but in that case the two individuals at the window, top-right, would be giants. This is a stylised, flattened and expertly balanced and patterned composition.

The wall round the corner is less vitrum coloratum in manner, as well as being longer in extension, and busier, than the Roman side of the mural. On the left of this façade, medieval Peckham is the site of Chaucer and others readying themselves to leave town and travel to Canterbury. The text in the box is from Canterbury Tales, although the riders next to it, at the top of the image, seem to be hunting rather than pilgrimageing.

And off we rode at slightly faster pace

Than walking to St. Thomas’ watering-place;

And there our Host drew up, began to ease

His horse, and said, “Now, listen if you please.”

That’s Nevill Coghill’s translation: the original is:

And forth we riden a litel moore than paas

Unto the Wateryng of Seint Thomas;

And there oure Hoost bigan his hors areste

And seyde, “Lordynges, herkneth, if yow leste.” [Chaucer, General Prologue 825-8]

In the lower left quarter, a horse leans down to drink from the River Peck, the watercourse which used to flow openly through Peckham Rye, but now only runs underground (it was enclosed in 1823, like many London rivers and streams). ‘Peckham’ comes from the Old English pēac and hām meaning ‘homestead (that’s ham, ‘home’) by a hill (that’s peak)’. The river is named after the village: ‘Peckham Rye’ is from Old English rīth, meaning ‘stream’.

A medieval knight, holding a lance in his right hand and a broadsword in his left, guards the border between this Chaucerian late 14th-century scene and, to the right the early 15th-century: specifically, 1415, and Henry V, looking splendid in his armour, ready to lead his army out of London to Southampton and so to France, just as soon as the assembled bishops and holy men have finished blessing his enterprise.

The next panel is dominated by the golden-ratio left-hand-side: Jack Cade’s rebellion (May-July 1450). Cade in yellow on his horse with his followers to his right, armed with their rural tools; to the left, behind the two soliders, are the citizens of London, who turned up to fight Cade’s army back at London Bridge. Four individuals cower in a tower, at the top. But the eventual defeat of the uprising is foreshadowed, or actually shown, by the two hanged men in the upper middle of the mural. A sharp piece of composition this: the gibbet almost looks, in Mannerist style, like a knight’s helmet, with dead men in its eyeholes. The sky is stormy, appropriately. Then at the bottom the two armed soldiers have their crossbows upside-down, which shapes invert the two arched gibbets above. The crowd is excellently done: each individual differentiated, but also rendered as crowd, a texture of tesselated elements that respeak the compositional logic of the image itself, the assemblage of mosaic tiles.

Cade’s horse, unlike Henry V’s fine white war-charger, is a yellow palfrey. His face, with its big rough beard, is more coarse than the kingly faces represented in the mural, and he reaches out to call on someone, or perhaps to call for help.

The border between Jack Cade and the 17th century is a tall white building, two heads janus-facing the past and the future. In front of it stands a bleached-white Roundhead soldier, turning his back on us and looking somewhat askance, as well he might, as Charles II rides back into London on 29 May 1660, his 30th birthday. One of his entourage waves a huge golden banner upon which is the royal coat of arms in a blitz of red, azure, gold and silver. I wonder if the woman, towards whom Charles is riding, the one in the gorgeous green dress, in amongst the crowd of long-haired Royalists, is signalling to the king her sexual availability by sweeping back the front of her dress. He was after all a notorious shagger, was Charles.

Finally, the mural comes up to date, blending to the left a Victorian set of factories and a horse-drawn omnibus with a central Pearly Queen and King halfway across a zebra crossing, whilst, to the right, the snout of a Hilman Imp, or similar, waits patiently. The Pearly Family seems a touch kitsch, to me. We could even call them ersatz, a tourist-focus confection, not a genuine element of London culture: like a ploughman’s lunch. But then, these are all tourist-eye scenarios, I suppose: famous moments of English history. And the pearlies’ clothes do add some visual intricacy to what is otherwise a rather drab downbeat ‘modern’ visual plane of this last image.

Arguably the overall progression of the lengthy image is not what one might call progressive, politically: oddly, for a piece of work commissioned by a Labour council under a Labour government, though perhaps not so for a traditional Catholic anti-Communist figure like Kossowski. Life through the history of Peckham is colourful, varied, full of beauty and pattern, but tells a particular story: first the Romans came, to conquer and ‘civilise’; then King Harry assembled a gorgeously apparrelled army to ride away and conquer France; then (presented in duller colours and overshadowed by the dangling corpses of two men) there was a popular uprising against the ruling class—but then, in quick order, the finely-dressed king rode into town on his caparisoned horse to be greeted by an orderly assembly of finely-dressed nobles, and that brings us up to the present day (of 1965), a little grey compared to earlier history, but under the watchful eye of police authority, some ordinary people cosplaying royalty. The intricate orderliness of the composition refracts a vision of popular order and hierarchy, a political conservatism, in which Cade’s rebellion is not only anomalous narratively, separated aesthetically, but automatically punished, capitally, even as it is happening. Know your place, peasant!

But it’s a gorgeous work of art. Mosaic lends itself to a stylised, cartoonish (not a word I use as disparagement): the bright colours and deliberate primitivism of the way perspective is used a hark-back to medieval illustration, Byzantine mosaic. In style as well as subject this is a piece of public art in which the people restore and affirm their connection to their past. The aesthetic is figures (human beings and horses) in space (mostly urban space, since this is a piece of art about a cityscape) and the use of high relief gives what could otherwise be inertness of tesselated elements an almost impasto verve. Kossowiski keeps the colourfulness in check with elements of pallor, and he is expert at filling-out crowds of people without losing their individual humanity or becoming over-busy.

The medium involves a certain flatness of representation (evoking what John Ashbery somewhere calls ‘the chic flatness of memory’—in this case, historical memory)—Clement Greenberg supposedly saw purity and flatness as modern art’s defining achievement. And the flatness does not detract from the vibrating urgency of this image’s quasi-pointilliste bricolage. In a sense the flatness of these compositions paradoxically compels depth: not because the images are in any meaningful sense rounded, but because they appear layered, amost laminated, background midground foreground, with the black outlines separating and so distinguishing these layers.

Mosaic involves a kind of simplifcation of representation. Gluing many tiles to a wall does not give the artist the subtlety or variety of a fine brush stroke painting or teh gradations of shading and contrast of other media. But this is not a bad things. The scale here is simultaneously greater than a conventional canvas—1000 square feet!—and also, in a sense, smaller, lesser. This is how Hilaire Belloc’s ‘The Inn Of The Margeride’ (from Hills and the Sea, 1906) starts:.

Whatever, keeping its proportion and form, is designed upon a scale much greater or much less than that of our general experience, produces upon the mind an effect of phantasy.

A little perfect model of an engine or a ship does not only amuse or surprise; it rather casts over the imagination something of that veil through which the world is transfigured, and which I have called “the wing of Dalua”; the medium of appreciations beyond experience; the medium of vision, of original passion and of dreams. The principal spell of childhood returns as we bend over the astonishing details. We are giants—or there is no secure standard left in our intelligence.

So it is with the common thing built much larger than the million examples upon which we had based our petty security. It has been always in the nature of worship that heroes, or the gods made manifest, should be men, but larger than men. Not tall men or men grander, but men transcendent: men only in their form; in their dimension so much superior as to be lifted out of our world. An arch as old as Rome but not yet ruined, found on the sands of Africa, arrests the traveller in this fashion. In his modern cities he has seen greater things; but here in Africa, where men build so squat and punily, cowering under the heat upon the parched ground, so noble and so considerable a span, carved as men can carve under sober and temperate skies, catches the mind and clothes it with a sense of the strange. And of these emotions the strongest, perhaps, is that which most of those who travel to-day go seeking; the enchantment of mountains; the air by which we know them for something utterly different from high hills. Accustomed to the contour of downs and tors, or to the valleys and long slopes that introduce a range, we come to some wider horizon and see, far off, a further line of hills. To hills all the mind is attuned: a moderate ecstasy. The clouds are above the hills, lying level in the empty sky; men and their ploughs have visited, it seems, all the land about us; till, suddenly, faint but hard, a cloud less varied, a greyer portion of the infinite sky itself, is seen to be permanent above the world. Then all our grasp of the wide view breaks down. We change. The valleys and the tiny towns, the unseen mites of men, the gleams or thread of roads, are prostrate, covering a little watching space before the shrine of this dominant and towering presence.

It is as though humanity were permitted to break through the vulgar illusion of daily sense, and to learn in a physical experience how unreal are all the absolute standards by which we build. It is as though the vast and the unexpected had a purpose, and that purpose were the showing to mankind in rare glimpses what places are designed for the soul—those ultimate places where things common become shadows and fail, and the divine part in us, which adores and desires, breathes its own air, and is at last alive.

As an account of the modular in art, an element with many applications, this seems to me profound. There is something of the childish, in a positive sense, about Kossowski’s ‘Greatest Hits of London History’ parade.

Some details. As distracted as I am by the second Roman from the left’s bizarrely huge right hand, I am delighted by the little feller popping out from the inside of that building to give us a cheeky wave:

And in the Restoration section, I’m curious as to the identity of these twelve people:

They look like a jury, although juries in England were all male until 1919 (and were typically so in the 1960s, since few women satisfied the property qualifications until those were abolished in the 1970s). Perhaps it’s a congregation in church.

How utterly gorgeous! Thank you so much for your detailed and insightful analysis of this beautiful mural, which I knew nothing about. I must make a journey down south to Peckham to see it. It sounds like an incredible work of art and very relevant to my research and teaching interests. I was particularly struck by how much this sounds like the work of an immigrant who has fallen in love with his adopted country and is perhaps overly eager to adopt its conservative narrative to demonstrate his assimilation.