2001: a Space Kirby-see

When I was an undergraduate I read an essay, though I cannot remember which one or where it was collected, written I think by John Hollander—my present-day desultory Googling is not helping me locate the piece—in which Shakespeare’s Tempest was discussed in terms of two key qualities: patience and reticence. Patience is (I quote from memory, which is, as you would expect, not likely to be precise) ‘that ability of a work of art to suffer and endure multiple interpretations, without which no artwork can survive.’ Reticence is ‘that ability not to speak out too blatantly, not conveying meaning and significance in too loud or simplistic a manner, but leaving as undetermined complexities and ambiguities of conflict and meaning.’ Hollander gives as example Verdi’s Otello which, he says, is a masterpiece, but it will be seen, he says, by comparison, that Shakespeare’s Othello is reticent. I think about that from time to time.

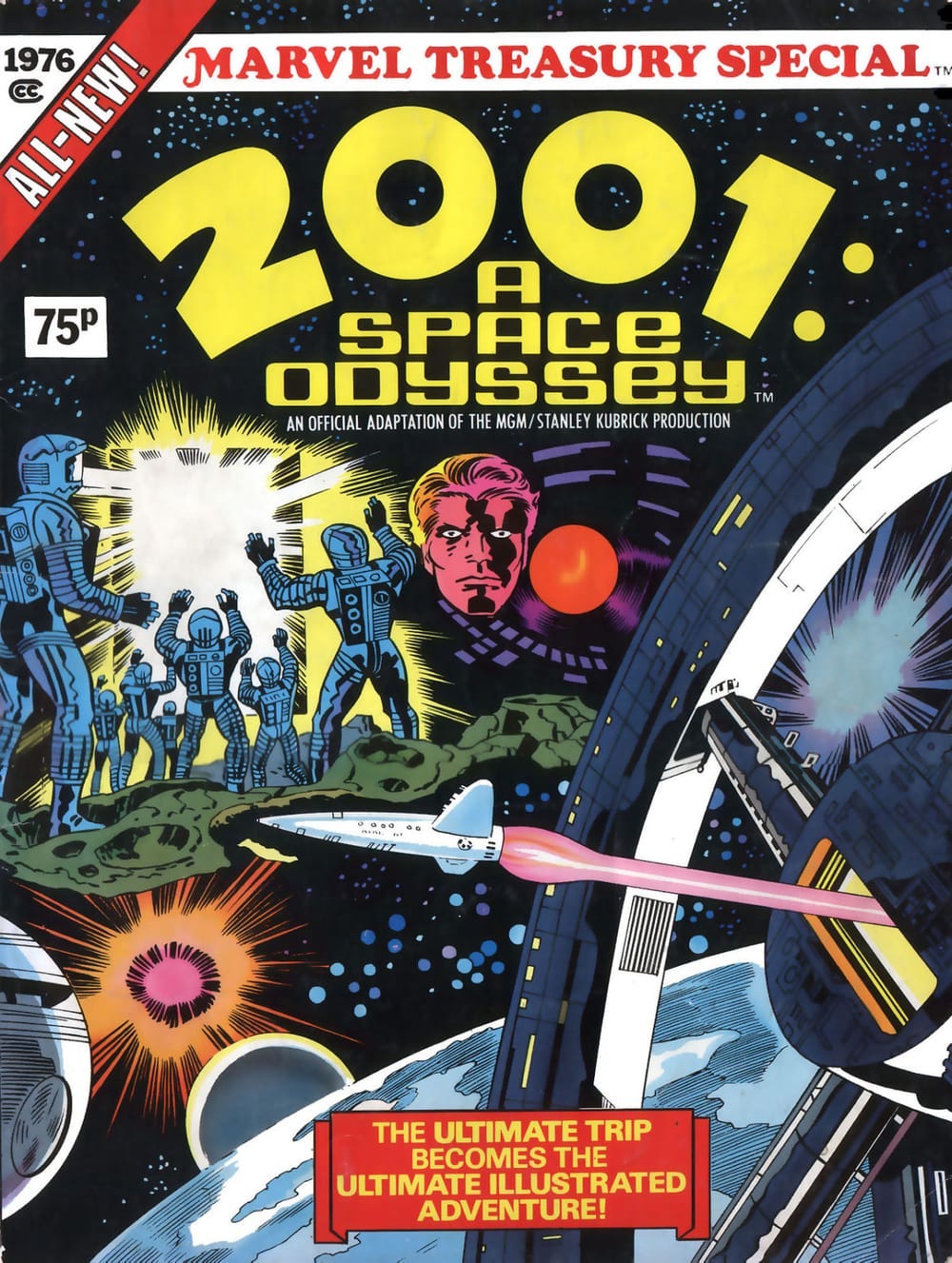

Anyway, here’s Jack Kirby’s gloriously outré, pop-fauvist 1976 comic-book version of Kubrick’s peerless 1968 movie. On the cover, there, the Earth-to-orbit shuttle leaves the space station dock on a jet of candy-pink exhaust flame (rather than arriving, in the movie, without any kind of fire emerging from its engine). Starbursts abound. A trick is missed, however, in going for:

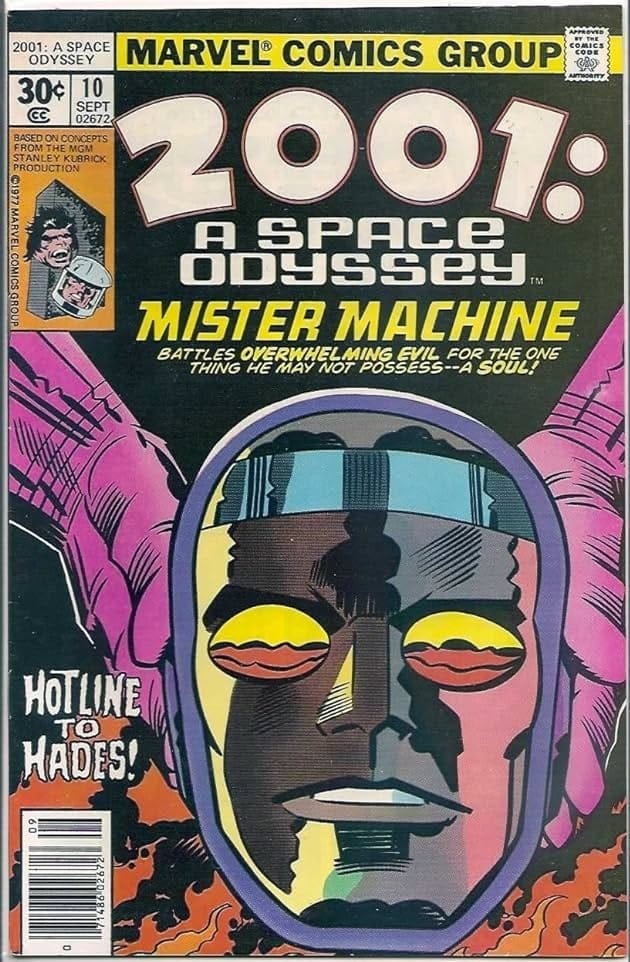

… when THE ULTIMATE TRIP BECOMES THE ULTIMATE COMIC STRIP was right there. Kirby had left Marvel late in 1970, after signing a lucrative deal with DC, but he was never happy at the other place and in 1975 he returned to Marvel, working on Captain America, creating The Eternals, and writing and illustrating this 2001 comic book (he wanted to do the same for a comic-book adaptation of The Prisoner, but that came to nothing). This 1976 ‘Marvel Treasury Special’ more or less retold the story of Kubrick’s movie, and was successful enough for Kirby to launch a new 10-issue comic series, set in the 2001niverse, but only losely related to the actual movie: ‘based on concepts from the MGM/Stanley Kubrick Production’:

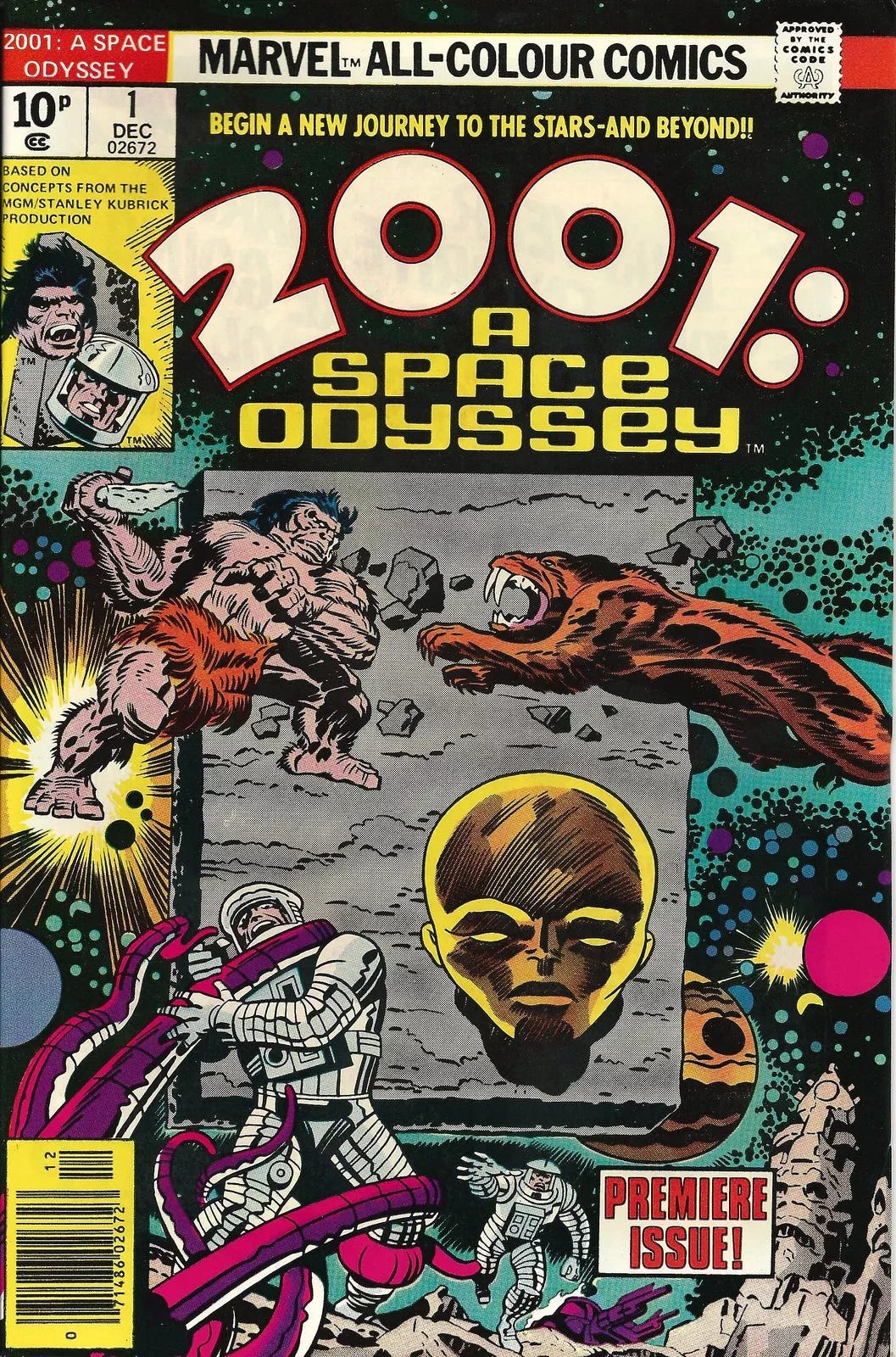

This series was still called 2001: A Space Odyssey, but followed the adventures of a different ape-man to the movie’s ‘Moonwatcher’: ‘Beast-Killer’—there he is on the cover of the first issue, proving nominative determinism correct by literally killing a beast—who also gains transcendent insight from a (different) Monolith. The story jumps forward to one of Beast-Killer’s human descendents, who is part of a space mission to explopre yet another Monolith, located on a rocky planet infested with pink-tentacle monsters. This machine (if the Monoliths are machines) doesn’t muck about with stargates and slow-paced aging in a five-star-hotel-room replica prior to rebirth: it straightoff transforms the spaceman into what the comic calls ‘a New Seed’.

This takes us up the issue 6 of the 10-part serial. In issue 7, New Seed zips around the universe and observes the misery, pain and death mankind inflicts on itself, ultimately transforming into two lovers, a male and a female, by which a new planet will be populated with a new race of, we assume, übermenschen. Übe-thousand-and-one a Mensch Odyssey. This still leaves three episodes to fill, so in issue 8 Kirbky makes a knight’s-move in story-direction with a wholly new character:

‘Mister Machine’ is an advanced super-robot designated X-51 (this character was later renamed later renamed Machine Man). Brilliant roboticist Dr Abel Stack has created the X-series, but there is a flaw in their design, and they go on the rampage. Mister Machine encounters yet another Monolith, which uplifts him to a place beyond his malfunction, such that he approaches human-ness, maybe even gifting him with a soul, or at least puts him on the Pinocchio-path to acquiring one. But Mister Machine has to flee the Army, who have desroyed all the other malfunctioning X-robots and are coming for him.

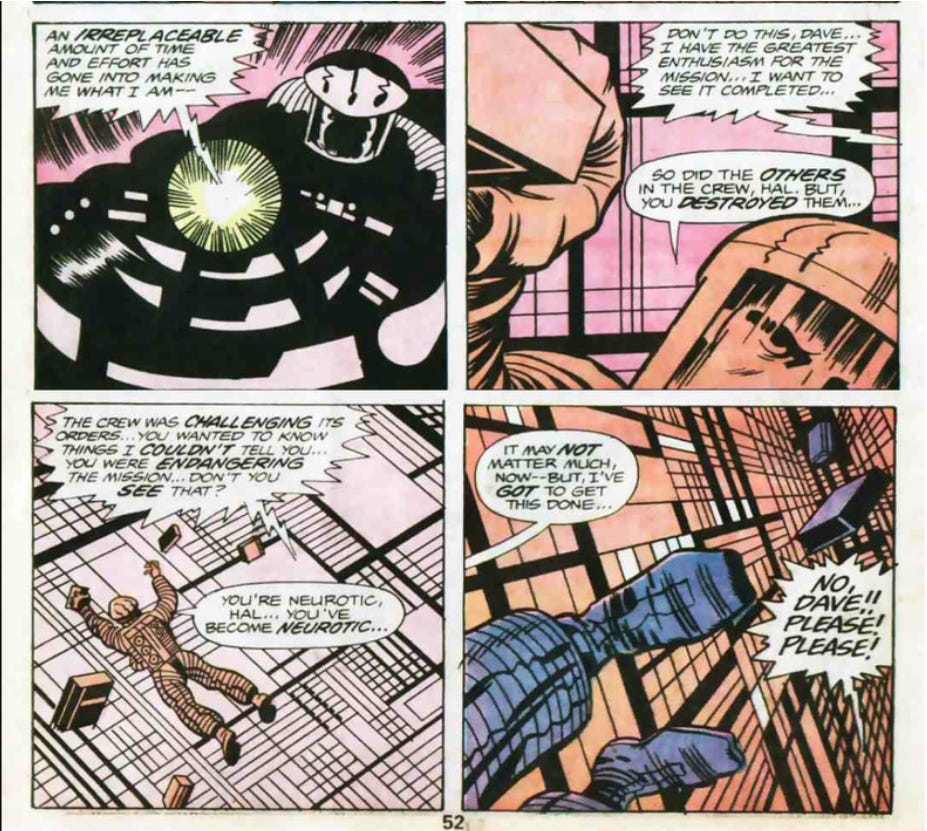

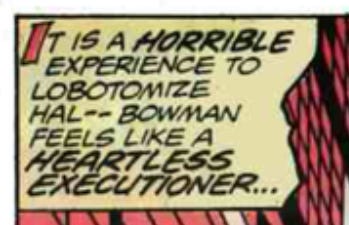

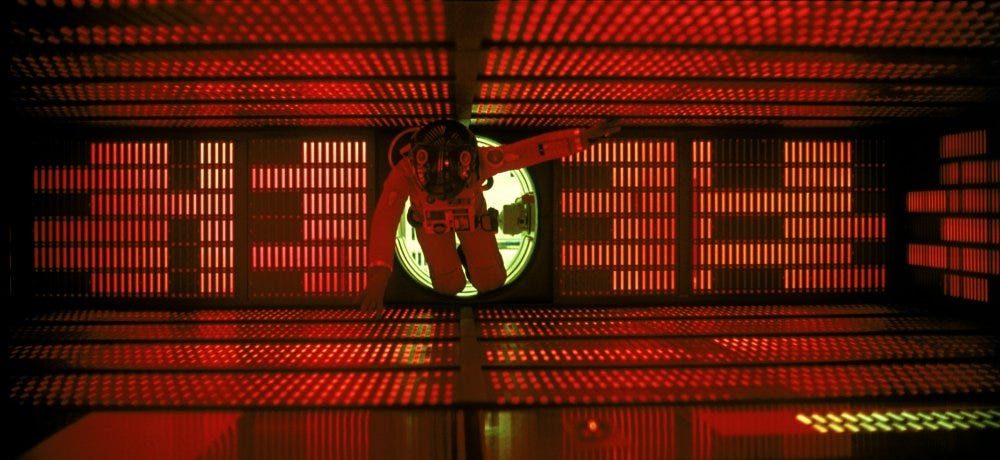

Julian Darius wrote a short book on this one comic: The Weirdest Sci-Fi Comic Ever Made: Understanding Jack Kirby's 2001: A Space Odyssey (2013), which talks about how mad the project was, and how unpopular: letters poured into Marvel complaining about the undertaking, and ten issues was all it got. But, like Verdi’s Otello, Kirby’s 2001, though it lacks reticence, and has not proved patient, has its own force and vigour. Where Kubrick slows and chills the story, building mood and tension, stretching the timescale and spatiality towards sublime expansions, Kirby is all punch and attack. So I ask you: which is more effective? The long sequence in the movie, where Bowman, his air-supply hissing sibilence, floats inside HAL’s ‘brain’ painstakingly dialing-down enough of the computer’s consciousness—removing what looks like mini-monoliths from his mainframe—as HAL himself affectlessly intones ‘stop—Dave—won’t you stop—Dave?’ in increasing ritardando? Or Kirby’s straight-to-the-point:

“NO DAVE!! PLEASE! PLEASE!” This is doing something else to Kubrick: and serving the story with a large helpings of Tell-Don’t-Show:

To be clear: my love for Kubrick’s 2001 exceeds the bounds of propriety. I sometimes debate with myself whether my vote for ‘greatest film of all time’ commits me to 2001 or Tarkovsky’s Stalker, but the truth is (and pace Stalker, which is a towering masterpiece of 20th-century art by any metric) there’s not really a contest. I love 2001 with a deep and abiding love. I love the actors and professional dancers who dressed in ape-costumes at Kubrick’s bequest and performed ape-ness so incisively, so brilliantly, that (allegedly) the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences didn’t nominate the movie for costume design (though they did for the much inferior ape-costumery of Planet of the Apes, some years later) because they didn’t realise these characters were humans in costumes and assumed they were actual apes. I love the match-cut that links the skyward flung-bone and the orbiting 21st-century spaceship. I love the slow two-part passage of Floyd to the moon, including the interlude where he meets Russian Reggie Perrin. I love all the deliberately-rendered longeurs of the Jupiter mission, jogging round the track, eating space-gunk, watching BBC 12 (a channel for which I still await, like Tristero, and which I promise to watch religiously when it finally arrives) …

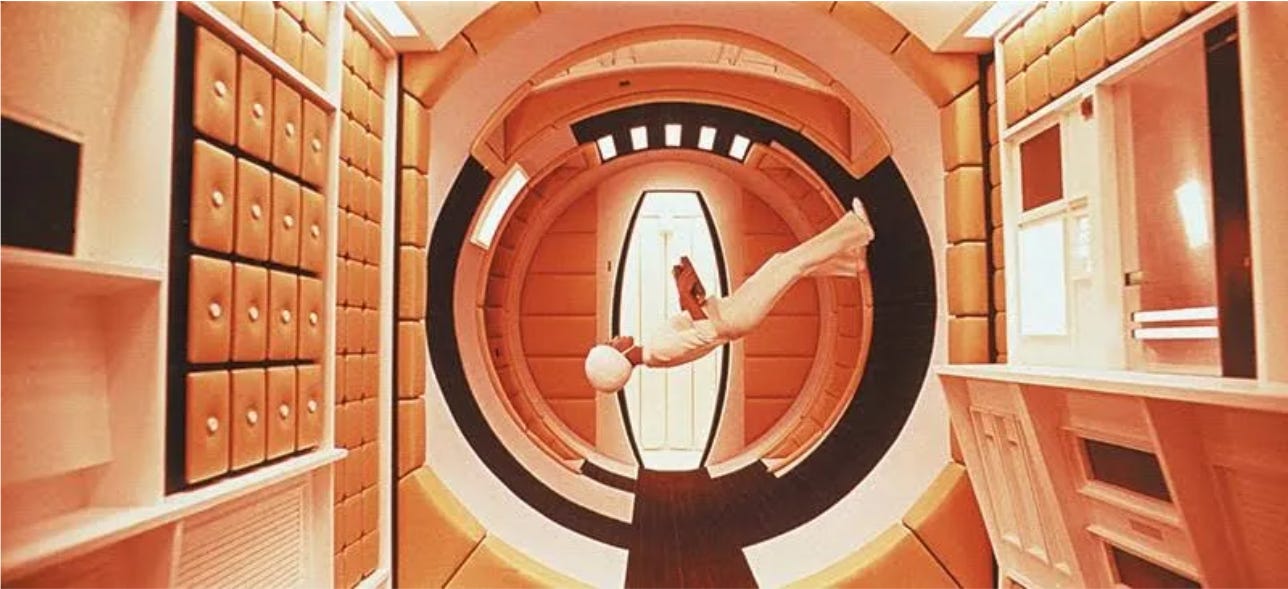

… and I love the drama of the communications malfunction, Poole’s death, Bowman being locked out, ‘I’m afraid I can’t do that Dave’, the superbly tense thrills of Bowman finding a way back inside, the justified pathos of Bowman shutting HAL down, the singing of ‘Daisy Daisy’ (on which, see here for a connection to my and SF’s guvnor H G Wells), the glorious Star Gate sequence and, best of all, the final step-through to Bowman’s death. There are (not to overshare) occasions when I wake in my bedroom, lying in the bed I share with my wife, and look down: at the end of the bedroom is a door that opens on a juliet balcony, flanked by two windows, each with shutters. We close the shutters at night and used to have a blind thet rolled down the door; but for reasons too boring to elaborate that blind is no more, so 4am me finds himself staring at a Monolith-proportioned block of blackness framed by glimmering pale-whiteness, like super-elderly Bowman in his big bed. Makes you think. Specifically about mortality.

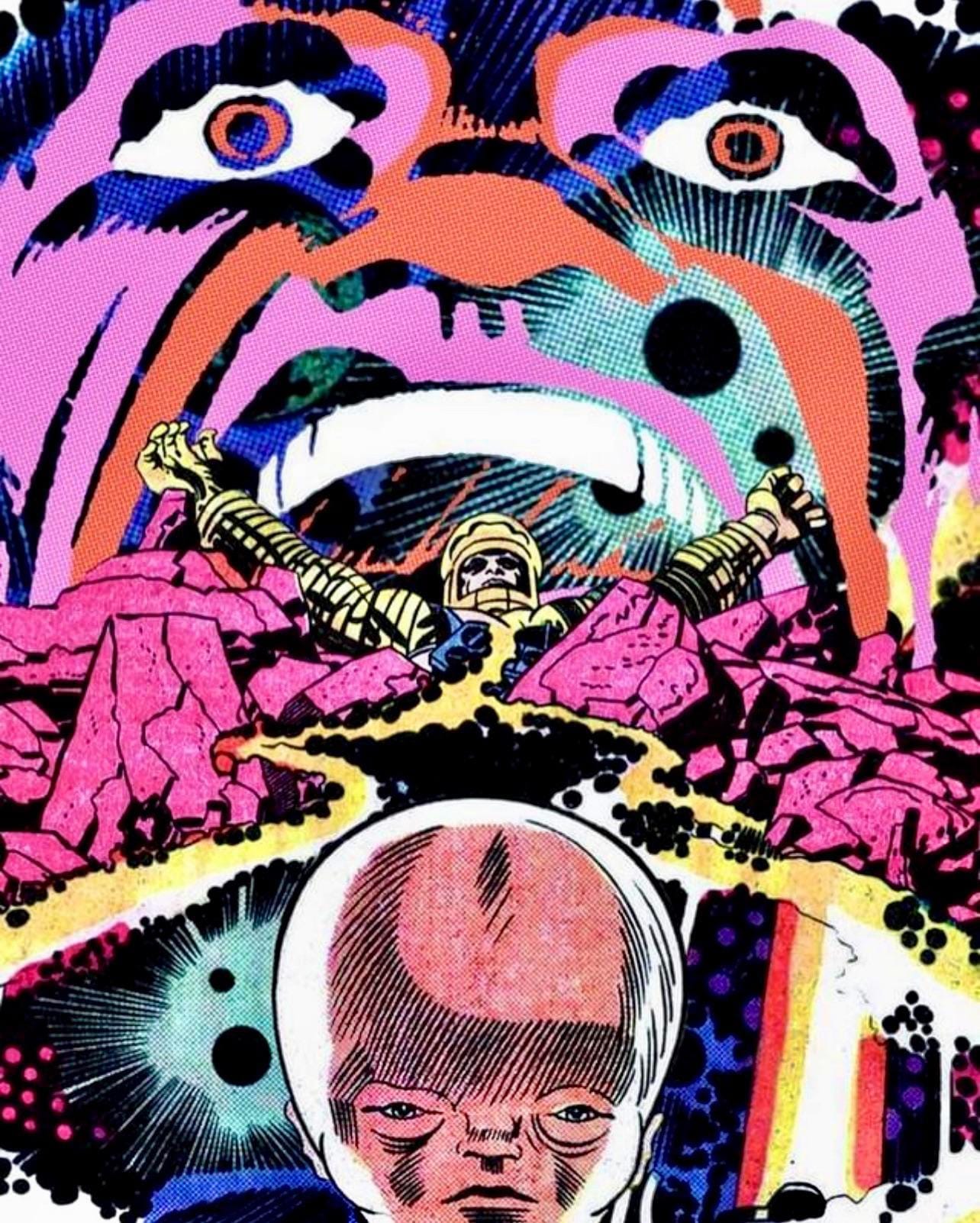

But Kirby is going for something else, here, evidently. This is a visual world in which it’s not enough for ape-man to bash ape-man’s skull with a bone (dramatic enough in the original movie)—a volcano must be exploding in the background, to provide an objective correlative for the drama, violence and excitement.

In place of Kubrick’s coolly orchestrated, balanced and poised framings, Kirby goes for a Peter-Jacksonian vertiginousness, forced perspective, Bowman (here) lurching in zero-g, his hand much bigger than his foot as he foreshortenedly grasps for us. Then again, Kirby’s black-white-mauve shocking-pink-purple colour palette is an exaggeration, but not an absolute distortion, of the muted psychedelia of Kubrick’s cinematography.