John Milton, Paradise Assured (?1682)

Briony Foster (ed), Milton's Paradise Assured (University Press of Augéres, 2024)

The discovery in 2017 of a single printed copy of Paradise Assured—the third volume, long thought lost, in John Milton’s trilogy that began with Paradise Lost (1667) and continued with Paradise Regained (1671)—was something of a nine-day wonder among Milton scholars. Almost all denounced it as a forgery, or some other kind of hoax. It is true that a small number of these experts have altered their views after being given the opportunity to examine the volume (it passed from its previous owner to the Canadian Bibliotheque Augéres last year, reputedly for a six figure sum) but most have stuck to their initial view, applying okham's celebrated razor both to the text itself and to the sometimes extraordinary claims that have been made about it. Professor Briony Foster, who has edited the volume for publication, was one of the few eminent Miltonists to believe the story of the book from the beginning, and she defends her position in this new edition at some length. The volume’s provenance only reaches back to a Belgian collector who acquired it in 1918, but as Foster points out: a lot of paperwork and other material was destroyed during the war, and she bases her faith in the genuineness of the article upon internal grounds.

Even those not inclined to dismiss the whole volume out of hand might raise objections to the likelihood of this book actually being by Milton. Some of these I will discuss below. But first, a brief account of the book itself. Paradise Lost (in its 1674 second edition) comprises twelve books of epic verse, a number modelled on Vergil’s Aeneid. Paradise Regained is four books, and, in Milton’s famous phrase, represents an example of ‘brief epic’ of which the Biblical book of Job is offered as a key example. With this third and final epic, Paradise Assured Milton divides his story into six sections. This, Foster argues, is a homage to Vida’s Christiad, a Neo-Latin epic in six books published in 1535 (Miltonists have long known of Milton’s admiration for Vida’s poetry).

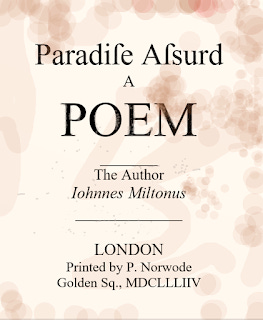

The single printed copy of Assured we have is all that remains of what was clearly (assuming the volume is genuine) a very small initial print-run. It was likely a rush-job: there is no licence notice and the date on the title page has somehow gotten garbled: “MDCLLLIIV”. Foster has her own reasons for thinking 1682 a likely publication date, although she also considers the chance that the work came out 1678, the year of Milton’s death, and concedes that it might have appeared as late as 1694. There are numerous typographical errors (Foster tabulates these in a seven page appendix). Evidently, the work passed through the printer’s somewhat carelessly.

The subject of Paradise Assured is the end of the world as detailed in Saint John’s Revelation. It distorts Milton’s sometimes rather sinuous (indeed, rather oblique) throughline to dispose it into the following table, but this is, more or less, the structure:

Book 1. The prophesied End Times. The Virgin Mary standing on a crescent moon appears to John on the island of Patmos, and tells him that the island is Christ. Christ then appears to John, relates a story about the moon goddess raising Patmos from the seabed and rebukes mankind for its sinfulness. John falls into a fit of ‘shame and ecstasie mixt’.

Book 2. Satan rouses his army in the underworld and leads them out through seven gates onto the Earth. They assault Jerusalem—the seven seals are explained as the seven outer gates of the city.

Book 3. The seven trumpets sound; with each Milton digresses into one of the ‘seven ages’ of the earth. The trumpets are explained as the seven inner gates of Jerusalem’s inner citadel.

Book 4. Satan’s army assaults the temple; the seven bowls are each filled in turn with blood that overflows. Each bowl corresponds to one of the entrances of the great Temple in Jerusalem.

Book 5. The Final Battle. Satan is defeated by Christ leading an army of the holy.

Book 6. A New Heaven and a New Earth are founded. The angel of the sun brings the book of life down to the holy land. The elect begin their return journey to God.

The business with Christ actually being the island Patmos is explained in the poem itself. Milton explicitly refers back to the famous epic simile of Paradise Lost in which Satan is compared to the oceanic Leviathan to which the unwary mariner anchors his boat thinking it an island, only to be dragged to a watery perdition. Patmos (the poem suggests a rather fanciful etymology for this name, linking it, via Πατ-, to God the Father) rises from the seabed as Christ rose from the dead, to form the virtuous mirror-image of Satan, a stable refuge for mankind.

It’s also worth noting that where the first five books are all between 770 and 940 lines long, the sixth book is nearly 1700 lines, and gets into some rather baffling obscurities towards its end. I shall return to these.

Certain questions press themselves, inevitably, upon any reader. One is: exactly when did Milton, blind and ill with chronic gout and kidney problems, write this lengthy text? Was it between Regained’s publication in 1671 and his death? Such a timeline is not impossible, of course, although it’s hard to see how the weakened Milton was able to revise Paradise Lost, produce a good quantity of prose and confect an entire epic poem from scratch; and the lack of any references in his letters, or in letters by his friends, to the work is suspicious.

Foster floats the argument that sections of the poem, ‘and perhaps many such passages’ had been written earlier—perhaps as early as 1664 she says—but she provides no external evidence one way or the other. Stylistically Paradise Assured represents a retrenchment, away from the more purged and austere style of Paradise Regained towards the fruitier or more bombastic style familiar from earlier work. This is one reason why Foster thinks significant portions of the poem might have been composed years before. Many readers, though, may find themselves struck that a certain cantankerousness, characteristic of old men in poor health, flavours much of the verse:

In various stiles sins passage hath stird waves

Most turbulent of all the rivers spate

Whose sound the eloquence of cataract

Chimes woe unto the earth: I broght

Not Peace, but the sword: and my gospel preach'd

Man hath corruptd, misconstrued and spoilt;

Nor shall my Church be only drensht with blood

Of its own mart[y]rs, z[ea]lots yet arise

To mirroir dark humillity and peace

And so revert upon your sons my love

As enmity enflamd with passions kiss

Grind hart on hart; so shal ruthless war

And persecution and fierce civil rage

Ravage the Christian world; intolrant pride

Usurping powr infallible, shall send

Its heralds forth with curses in their mouths

And fetters for mans conscience in their hands;

To bid the unenshrivend nations kneel

Under their conqu’ring standard and adopt

The creed of murderers, who, in the place

Of the pure bond of charity, present

A forged scroll blurrd and defacd with lies,

And impiously inscribe it with my Name.

These are religions traitors, and from them

An ample harvest shalt thou reap, O Death!

As is well known, Thomas Ellwood jotted down in a memorandum book what has long been believed to be ether the opening lines of Paradise Assured or some kind of unpublished coda to Paradise Regained:

That Paradice first lost and then regaind

Yet station’ d o[n] precarous human hearts

That blind or prideful yet may cast away

As ignorance discards a priceless pearl

That could release his family from debit […]

Bland enough. But, oddly, the poem as published opens quite differently:

Numinous Muse, that movd my former song

Of Adams loss and greater Adams taske

Most hard and bitter, to unfall that world

I here again in humble ernest press—

Thou tender spirit, whos invirtuing Force

Suffuses stil the tangeunt human air

And so enspires and interanimates

The finer pieties of human hope.

Now, Holy Word, culminate my last Song

And so rowse fulminating fire from of[f]

The high and diamant peak of Helicon

To now illumine all this mortall world

That paradise once lost and but regaind

With such and painfull sanguinary hurt

Be made secure, and firm establisht thence

For all eternity of mortless time:

All banishment of dark by all thats light

From granit shield of fathers Patmos raisd

Where ere the Cytherean washed her face

And now the eremite endavouring pray

Beneath the Throne celestial and true.

Now, this is interesting enough, although how interesting depends upon the extent to which you are prepared to accept Foster’s argument that this poem is indeed echt Milton. So far as that goes, the real sticking point is not Books 1 – 5, which, though sometimes wayward, are in line with the sorts of things Milton has elsewhere written. The sticking point is Book 6.

In this final book, after a couple of hundred line of gaudy but striking description of the New Jerusalem, all gold-tiled streets and gemstone-studded buildings under a perennial swift sunrise, Milton does something odd. By ‘odd’ (Foster doesn’t use the word) I mean: unprecedented for Milton, something not hinted-at in any of his prose, Latin or English. He reverses time. Foster quotes a number of abstruse sources that may have been behind this conceit, a couple of Neoplatonists, a pamphlet by Newton, and she makes much of Angélique Arnauld’s book Passage chronologique de la rivière Jordain (1642)—hard though it is to imagine Milton being persuaded by a Janesenist. Paradise Assured does mention the story that the Jordan miraculously reversed its flow when Jesus was baptised in it.

When Death itself reverted back on Life

The very bre[e]ze turbilliond and backt

Round Orebs height, and Jordans mighty flow

Stood horrent and stepped back at whence it came.

None of this is laid out with what you might call crystal clarity, but in amongst the pious ejaculations and paeans to ‘th’obscurity of Light that veils the veil’ (whatever that means) a narrative does sort-of emerge. We might summarise it like this: the apocalypse is the end of time, in the sense that there is no further (forward) time beyond it. But it is not the end of the flow of time, which rather reverses and starts back again towards its source. God sets a kind of temporal antechamber—a thousand years, as mentioned in St John’s vision—in which the last business of the former iteration of time is wrapped up, not least the final punishment of Satan, described with grisly relish by Milton:

Satan meanwhile a million fathom deep

At bottom of the pit, in mangld mass

With shatterd brest and broken limbs enspread,

Lay groaning on the adamantine rock:

Him the Strong Christ with aethereal touch

Made whole in form, but not to strength restord,

Rather to pain and the acuter sense

Of shame and tormend; hidious was the glaire

Of his blood stre[a]ming eyes and loud he howld

For very agonue, whilst on his limbs

The massy fetters, such as Hell alone

Could forge in hottest sulphur, were infixd

And rivetted in the perpetual stone:

Tho worst of all these [a]gonies was that

Corruption foul, Time’s daughter, set

The first the fiend had ever felt such hurt

Her teeth in flesh &d bone, and brought a foame

And rank dissension of sinew and flesh

Through a decay of aye a thousand year

Until by sharp degrees he was dissalved

And, mote by mote, his consciousness unpickt.

The righteous, though, do not experience this thousand-year postscript. Rather they begin to live a completely different mode of time—running backwards towards the divine fiat lux. Milton’s theory, if we piece it together, seems to be: before the Fall time ran smooth and lustrous, ‘as Oxus clean or Indus bright/Unruffled and enriching in their flow’. The Fall polluted this stream, since when time has been both choppy and (to use the anachronistic word) entropic: moving sluggishly for the young and too rapidly for the old, whirlpooling around moments of pain to sharpen them and carrying away our joys and memories as mere flotsam. Times, as we have all noticed lately, have been hard.

The assurance of Milton’s new paradise is the reversal of time into a new, clean flow. In remarkable passages, the poem describes the saved living their lives—deathless now—in the new landscapes of this timeflow, from which they are able to observe all the events and people of our history, viewed in reverse. History is a story that is told now, and so Milton is able to revisit and clarify the problematic of free-will versus determinism that is such a feature of Paradise Lost’s armature of theological justification. Now it all seems simpler, somehow: then we were free to chose (‘then’ is now for us all, at this moment—the one in which you are reading these words), but now the story is over, and our choices are part of that narrative. Because time runs both ways, from the creation to the apocalypse and back Milton can present both these things as being true simultaneously—the elect, living in the timeline that runs back to God’s creation, pass the exact moment Adam chooses to disobey God’s instruction. Then he had freedom to choose; now his choice is woven into the fabric of time, inevitable and unchangeable. It is illustrative.

Six thousand years have passed, and then another six thousand (what shall we say?) anti-years, 12,000 in all, and—like passengers in a boat returning along a parallel channel and passing new folk just setting out—the elect can observe Adam fallen jerk backwards into grace. This is the moment when, from the point of view of the elect travelling back, Adam’s choice has happened. It is as baked into history as Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, or Milton's death in 1674. But from the point of view of Adam life and is absolutely open and choice-free. It’s like Einstein’s thought-experiment with passengers on a train passing observers in the train station. Not, of course, that Milton says anything quite like that.

There’s another important detail. The main business of the elect, passing along this reverse timeline—presumably at one second per second, though Milton doesn't specify—is observing the previous timeline (our timeline) and judging. As they pass ‘our’ seconds crosswise, they look over and see us. Some of us are, at that very moment, dying. This is the elect’s great work, ‘givn by God and so accepted/With effulgent gratitude’. With some they reach across and, at the moment of death, yank the virtuous soul over into their timeline. With others they—don’t. What happens to those delinquent souls? The poem is not entirely clear, but the implication seems to be: they are left to the entropic decay of that timeline—our timeline—and will eventually, one presumes, dissipate after the manner of Satan’s terrifying dissolution in the antechamber of forward-time, the last milennium of ultimate decay. But that’s not where Milton’s emphasis is. Instead he stresses the way the post-apocalyptic ‘reverted flow of Jordain’ sweeps the elect ever closer to God:

Not as when th’sun arizes newly keen

To level horizontal thro misty aire;

Nor yet when sinking orb with settling touch

Coaxes the horizon to a blaze of red;

But rather as tho beams unspread and rush

In eager congregation inward, and

Unite back in intensifying clench

Of brilliancy and eer increasing bright

Appro[a]ching GOD againe who is our home.

It is a conceit that becomes, for Milton, the key to all mythologies. Everything is explicable in terms of it. Prophesy? Messages from the elect, for whom our future is their past, telegraphed by some means from one timeline to the next. Miracles? Eddies in which timelines flow together such that the laws of what Milton thought of as ‘natural philosophy’ become puzzled together, and corruption rolls back into purity, illness into health, death into life. This theory is even used to situate the Trinity: God, the Creator (or Father) stands at the beginning; Jesus in the midpoint of both streams, looking both forward and backward, and the Holy Spirit is the twinned direction of the flow. When, as in the passage quoted above, Milton invokes the Holy Spirit as his muse, it is not merely a form of words.

This is where Professor Foster's edition strays into numerology; and, according to her more severe critics, into sheer bizarrity too. There has been little evidence of Milton's engagement with mystic number theory (unlike, say, Isaac Newton, who was passionate about the subject) but it is plausible that he had some interest in the topic. Foster takes such interest as axiomatic. The number seven, thrice repeated, recurs in Revelation, and so in Milton's poem. 7 x 7 x 7 = 343. ‘In November 2017, exacty three hundred and forty three years after Milton's death, this copy of Paradise Assured came to light,’ says Professor Foster. ‘Can there be any doubt that this denotes the most profound significance?’ One may, perhaps, be permitted a modicum of doubt, although Foster goes further: she believes, it seems, that the republication of Milton's lost work, exactly 343 years after (though as we have seen, the actual publication date is unclear) will trigger a worldwide renascence in Christian eschatology that will, in turn, activate the end of the world. A sober head might doubt that 2026 will see the apocalypse, although given what we have seen over the last few years, perhaps it's not so unlikely as all that. ‘I have every hope,’ she says at the conclusion of her introduction, ‘that I will soon be making that retroactive passage back to God, and that a cube of years will bring me to a meeting with John Milton himself; that he and I will travel onward as his eyesight restores itself, and his youth returns, and his joy in God grows hale and strong again.’ Paradise Assured, or Paradise Absurd? It is, I suppose, for the reader himself, herself, to determine.

------------------------

Correspondence

To the editors. Dear Sirs and Madam. You have obliged me to seek, and pay for, legal counsel with a view to compelling you to publish this letter, having refused to print my previous two. It is unconscionable. You are very well aware that since writing my review of Professor Foster's edition of Milton's Paradise Assured I have undergone a change of heart, and yet you refuse to remove the offending review from your website, or add the disclaimers I have asked for. My tone in said review was not merely dismissive and rude; it was, I now know, blasphemous. Professor Foster is still alive as I type, and yet I know she dies early next year. I know this because her returning form has contacted me from the patrallel retrotimeline and provided me with proofs of the TRUTH of everything she says, inspired by John Milton's poetry. We are very near the end of the world my friends, and levity is not the correct tone in which to address these matters. It is a matter of life and death, eternally speaking. It is not a matter not not a matter of some tribal God of the Middle Eastern wastelands, but of time travel, of an engine of sublime potency that cast off this, our timeline from its originary vastness, limiting its range such that it curves back hard upon itself. Of course, primitive people thought in terms of gods and wonders, and of course a figure like Milton rationalised it into his belief system but, sirs, madam, an atheist even such as I can see the ways in which visitants from future metamorphosis, such as Professor Foster, might use their superior temporal perspective to impart WISDOM. You must heed me. A.R.

The Editors reply. Having taken legal advice of our own, we have agreed to publish Professor R---'s uncharacteristically intemperate communication in the pages of this journal. That advice also counsels caution in expressing in a public forum any kind of value judgment upon the letter's contents, but we can, at least, express here our sympathy for him and his family at the news, recently reported, of him having lost his tenure and his restraint under the terms of the mental health act.